Features

Herbicides

Seed & Chemical

A whammy on wild oat

The results from a nine-year study show that using good cultural practices, along with herbicides, helps reduce the risk of developing herbicide-resistant weeds and boosts crop yields.

The study focused on wild oat, one of Western Canada’s worst annual weeds. According to John O’Donovan, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AFFC) and one of researchers involved in the study, wild oat is a major problem on the Prairies, and it has been so for many years.

“Wild oat also has a fairly high propensity to become resistant to herbicides. We started noticing that at the end of the 1980s, when we saw resistance developing in wild oat to a number of herbicide groups: the Group 1 herbicides, Group 2 herbicides and [Group 8] herbicides like Avadex BW and Avenge,” he says. “Since then, some wild oat biotypes on the Prairies have developed multiple herbicide resistance to two, three or even four herbicide modes of action, making the weed even more challenging to control.

O’Donovan worked on the study with AAFC colleagues George Clayton, Neil Harker and Kelly Turkington. The researchers were interested in weed management strategies that included both herbicides and cultural practices for several reasons.

“Way back before we saw herbicide resistance developing, we felt that if good cultural practices were used, then maybe not as much herbicide would need to be applied. So it made sense from an economic and environmental perspective,” O’Donovan explains.

“Then we saw herbicide resistance developing. That really started to emphasize to us that relying totally on herbicide application was not sustainable into the future,” he says.

The researchers initiated the study in 2001, establishing plots at Lacombe, Beaverlodge and Fort Vermilion in Alberta, and at Brandon, Man. In that first year, they broadcast wild oat at 100 seeds per square metre at each site to supplement the natural wild oat populations.

The study evaluated the effects of four treatment factors. Three involved cultural practices: continuous barley versus a barley-canola-barley-field pea rotation; a lower barley seeding rate (200 seeds/m2) versus a higher rate (400 seeds/m2); and a semi-dwarf hulless barley variety versus a tall hulled barley variety.

The fourth factor was the herbicide rate, with a comparison of 25, 50 and 100 per cent of the recommended rate. O’Donovan emphasizes, “We were not comparing herbicide rates to advocate that farmers go below the label rate. [In fact, other research has shown that reduced herbicide rates may result in faster development of some types of herbicide resistance.]

“We used the lower rates because, in our small plot experiments, we tend to get more efficacy from the herbicides than farmers would for large areas, like quarter sections or larger,” he says. “The lower herbicide rates on the plots helped simulate the lower herbicide effectiveness in farm fields that occurs due to weather conditions, problems in herbicide application timing and/or other issues.”

The study’s first five years produced several key results. “We found that each of the four factors was very important in terms of controlling wild oats,” O’Donovan says. “As expected, the higher we went on the herbicide rate, the better wild oat control we got.

“We also found that a stronger competitor [the tall hulled variety], a higher seeding rate and a more diverse rotation were very important for enhancing wild oat control, when combined with a herbicide. And that effect was greater at the lower herbicide rates than at the recommended rates,” he says.

So, given the less effective herbicidal control that occurs in field-scale applications, these three cultural practices would be very helpful in ensuring good weed control. As well, if a field already has some herbicide-resistant weeds, then these cultural practices could help to compensate for the reduced herbicide effectiveness.

Soil seed bank and herbicide resistance

The researchers continued the study for another four years, to 2009, at the Beaverlodge and Fort Vermilion sites. They used the same treatment factors except they changed the semi-dwarf cultivar from a hulless to a hulled cultivar.

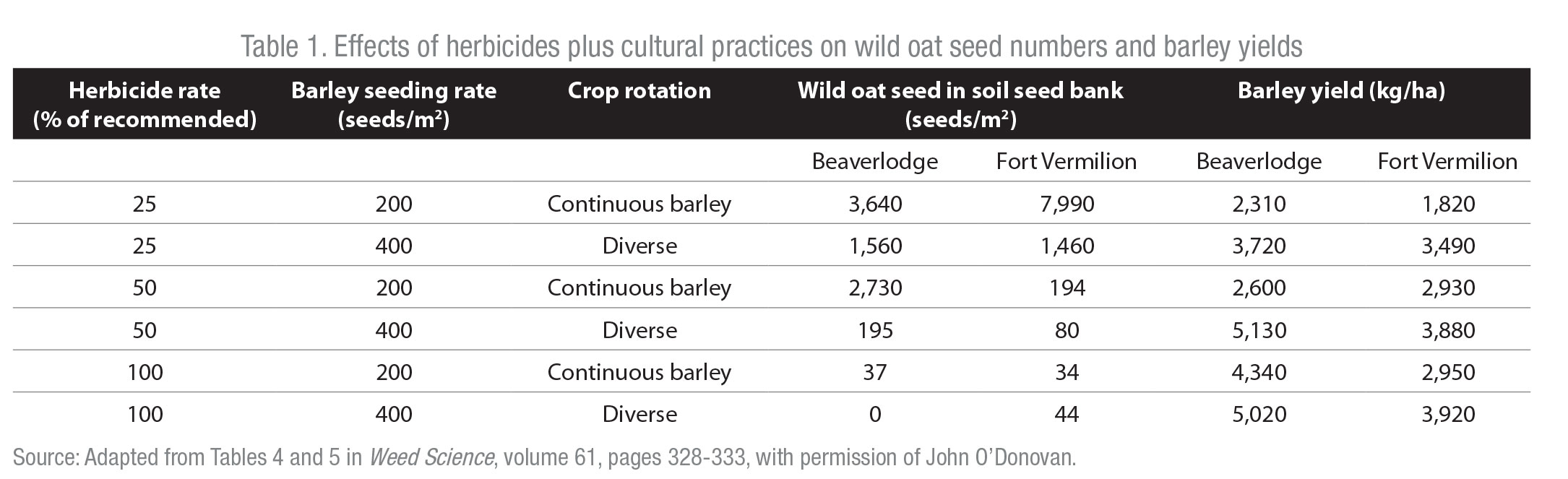

In this phase of the study, they examined the long-term impact of the four factors on the number of wild oat seeds in the soil seed bank and on barley yields in the final year of the study.

“The soil seed bank is crucial in terms of herbicide resistance,” O’Donovan explains. “Modelling studies have shown that the more seed entering the soil seed bank, whether it be wild oat or other weed seeds, the greater the likelihood that resistant weeds will be selected for. That makes sense because the more seeds you’ve got in the seed bank, the more likely it is that there’s a seed in there with a mutation that results in herbicide resistance.

“Now if you ask anybody what is the best way to reduce wild oat seed getting in the soil seed bank, they’d say use a good herbicide. And that is true, but it is also a bit of a dilemma. Because it is also true that the more you use a particular herbicide, the greater the likelihood of selecting for resistant weeds,” he adds.

The higher seeding rate combined with the diverse rotation – the optimal cultural practices in this phase of the study – resulted in much less wild oat seed in the soil seed bank compared to the plots with the lower seeding rate and continuous barley – the suboptimal cultural practices.

In contrast to the study’s first phase, the two barley cultivars used in the second phase were about equally competitive with wild oats, and the semi-dwarf variety had higher yields. So it appears that, in the study’s first phase, the semi-dwarf variety was less competitive because it was hulless, rather than because it was short.

Hulless barley is generally less competitive than hulled barley when seeded at the same rate. In hulless cultivars, the embryo is more exposed during seeding, so it is more easily damaged, resulting in poorer emergence and less competition with weeds. Thus higher seeding rates are recommended for hulless barley. For example, in other research, O’Donovan found that, for the hulled variety AC Harper, a seeding rate of 300 seeds/m2 was needed to achieve the target plant population of 200 to 240 plants/m2, but the hulless variety Peregrine needed a seeding rate of 400 seeds/m2 (and a seeding depth of about an inch) to achieve the target population.

The effect of the optimal cultural practices in reducing wild oat seeds in the soil seed bank was especially noticeable at the lower herbicide rates (see Table 1). And at the Beaverlodge site, that effect was evident even when the full herbicide rate was used. “For example, where we had the suboptimal cultural practices and the full herbicide rate, we had about 40 wild oat seeds per square metre in the soil seed bank. But where we had the optimal cultural practices plus the full herbicide rate, we had less than one wild oat seed per square metre,” O’Donovan says.

“So we got greater than a 40-fold decrease in the wild oat seed in the soil seed bank when we used the optimal cultural practices compared to the suboptimal cultural practices.”

The researchers also found that barley yields were generally better where the optimal cultural practices were used for the nine years. “On the plots with continuous barley, barley disease built up over the years, which resulted in the reduced yield,” O’Donovan explains.

Although using the higher seeding rate alone helped reduce the amount of wild oat seed in the seed bank, it was not nearly as effective as combining the higher seeding rate with the diverse rotation. O’Donovan notes that there are numerous other reasons to use diverse crop rotations. For example, research shows diverse rotations reduce a wide range of weed, disease and insect problems. “With the high price of a crop like canola, it may make economic sense in the short-term to shorten crop rotations, but over the long-term, all of these factors come into play.”

March 31, 2015 By Carolyn King

After the first five years of the study The results from a nine-year study show that using good cultural practices

After the first five years of the study The results from a nine-year study show that using good cultural practices