Features

Agronomy

Weeds

ICM systems for wild oat control

In cropping systems across the Prairies, wild oat control and concerns of herbicide resistance continue to challenge many growers. Current annual cropping systems are increasing the selection pressure for wild oat resistance, which is rapidly expanding across the Prairies. In Alberta alone, more than 50 per cent of all wild oat populations have at least Group 1 resistance and some have other herbicide resistance as well.

In 2010, Dr. Neil Harker, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at Lacombe, Alta., initiated a five-year project to evaluate management strategies to reduce selection pressure for wild oat resistance to herbicides. “The objective was to look at cropping systems and cultural management methods that could reduce our reliance on wild oat herbicides,” explains Harker. “Similar to previous studies, we included cultural practices such as higher seeding rates and silaging to prevent wild oat from going to seed. However, in this study we added a new strategy of including different crop life cycles to determine if diverse crop rotations would influence wild oat production, wild oat seed bank, soil microbes, crop yield and crop quality.”

Previous studies included only summer annual crops such as barley, wheat, canola and peas. Wild oat is also a summer annual weed, so continually growing summer annual crops favours wild oat growth. In this study, researchers added different crops including alfalfa (perennial) and winter annual crops such as winter wheat, winter triticale and fall rye. In the years these latter crops were grown, no herbicides were used for wild oat control. The project was conducted at eight sites across Canada, including Lacombe, Lethbridge and Edmonton, Alta.; Scott and Saskatoon, Sask.; Winnipeg, Man.; New Liskeard, Ont.; and Normandin, Que.

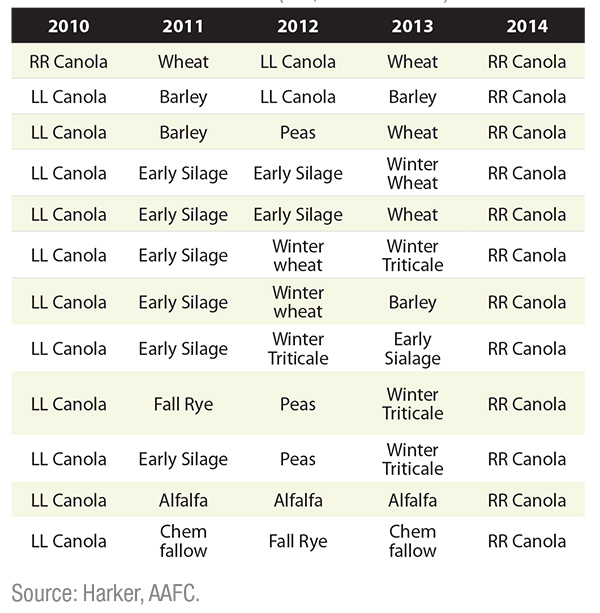

At the start of the project in 2010, wild oat populations were established in canola in all locations. Natural wild oat populations were supplemented to ensure adequate, uniform wild oat populations for the study. Crops included canola, alfalfa, early-cut barley silage, winter triticale, fall rye, peas, winter wheat and wheat in various rotations (see

Table below). Seeding rates in cereals were usually double the normal rate. Wild oat herbicides rates were 0, 50 or 100 per cent, while broadleaf weeds were treated with full herbicide rates. Wild oat density and biomass, crop density, yields, and biomass were collected each year.

“For the alfalfa, early silage and winter annual crops treatments, no wild oat herbicides were used for the three years from 2011 through 2013,” explains Harker. “For those three years, there is essentially zero selection pressure for wild oat herbicides. All of the experiments will continue through to the end of the 2014 crop year, with canola being grown in every location to provide a good comparison of what has happened over the five years of the study. So although we don’t have final results yet, the preliminary findings are very encouraging.”

Rotation treatments for the experiment. Some rotations were duplicated with varying crop seeding (1x or 2x) and/or herbicide rates (0%, 50% or 100%).

|

Preliminary results show that most plots with alfalfa, or silage and winter annual crops – and no wild oat herbicides – had wild oat biomass similar to the canola-wheat check rotation with 100 per cent wild oat herbicide every year. At the end of 2014, the final data collection will be completed including a wild oat seed bank determination to see whether or not the levels have changed over the five years of the study.

“We expect the final results to be similar to the preliminary findings and are encouraged to see that the results from some diverse rotations in integrated systems without wild oat herbicides can be as effective at managing wild oat as a typical summer annual canola-wheat rotation with full herbicide-rate regimes,” says Harker. “The results will provide growers with options to reduce herbicide expenditures, reduce selection pressure for weed resistance, and to grow canola in more sustainable rotations.”

However, the challenge is that few growers are willing to include more diverse rotations in their cropping systems. They have to weigh the short-term gain of a canola-wheat rotation, for example, with the long-term delay in herbicide resistance of more diverse rotations. Growing dominantly summer annual crops over and over again puts pressure on summer annual weeds, which are more likely to become resistant to whatever herbicide is being used. Adding diversity to the system can help reduce the selection pressure for herbicide resistance and delay the development of resistance.

Harker emphasizes that growers and industry need to think about other management options to reduce selection pressure now as the risk of herbicide resistance increases. “Along with wild oat herbicide resistance, other concerns such as kochia resistance to glyphosate in the west and three other glyphosate-resistant weeds in the east, need to be addressed. We must act now to delay the selection of glyphosate resistance in a species that threatens Canadian agriculture even more than kochia – wild oat.”

March 19, 2014 By Donna Fleury

Alfalfa in rotation provided the same level of wild oat control as an annual crop with herbicide control. In cropping systems across the Prairies

Alfalfa in rotation provided the same level of wild oat control as an annual crop with herbicide control. In cropping systems across the Prairies