Features

Insect Pests

New (old?) insect threats and the “old guard” of beneficial insects

Breaking down the big players in the world of beneficial insects.

June 12, 2020 By Presented by Tyler Wist, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, at the Top Crop Manager Plant Health Summit, Feb 25-26, 2020, Saskatoon.

Macroglenes penetrans. Photos courtesy of Tyler Wist.

Macroglenes penetrans. Photos courtesy of Tyler Wist. First, let’s define what a “beneficial” is. If it’s an insect helping me, it’s a “beneficial insect.” The beneficials that I’ll discuss here provide biological control, and are further defined as predators and parasitoids.

Western Grains Research Foundation has funded the Field Heroes project. This is a campaign championing beneficial insects. What I’m going to do today is teach you guys what a beneficial insect looks like and what they’re doing in your field, and maybe that will make you more apt to protect them. What Field Heroes is trying to do is to take away that “nothing to lose by spraying” mindset. If you are on Twitter, you can follow Field Heroes, @FieldHeroes and you can find it on the web at www.fieldheroes.ca.

No talk on beneficial insects is complete without talking about – I call it “#AAFCbugbook,” because this name is super-long to say – “Field Crop and Forage Pests and their Natural Enemies in Western Canada.” It’s available in print or you can download it from the Prairie Pest Network Monitoring Blog.

The Prairie Pest Monitoring Blog is a great way to get information on insect pests and beneficials and you should all sign up to receive emails. It’s run out of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and includes input from the provincial ministries of ag, but it’s been funded for the last 20 years by pretty much all the grower groups through checkoffs, and so thank you to them for funding this service to agriculture.

Wheat midge

I’m working on wheat midge, and this is one of the “big bads” in wheat. It’s been kind of suppressed for the last little while, but if you get $130 million in yield losses like we did in the 1990s, that’s why you know it’s a “big bad.”

Ag Canada has thrown a lot of research at it. Back when the wheat midge first reared its ugly orange head, they had six or seven full-time research scientists working on this problem. At the same time, we had over 500,000 acres sprayed and we still got crop losses. Ian Wise and Marge Smith, two of the scientists who were working on this, called this “the most serious insect pest of spring wheat in Western Canada.”

Let’s define what is a parasitoid. This is a parasite that kills its host. A good parasite doesn’t kill its host, but a parasitoid does. Wheat midge has a parasitoid, Macroglenes penetrans. It is little, it is black, and it goes after eggs and first-instar larvae of the wheat midge. This one stays inside the wheat midge larva and it doesn’t kill the wheat midge until the following year. Wheat midge overwinters as a third instar in a cocoon and when it is time to emerge in the late spring, instead of getting a wheat midge you’ll get one of these Macroglenes penetrans wasps coming out of the soil. They can reduce about 40 per cent of your overwintering population of wheat midge.

Macroglenes penetrans is why you don’t want to spray about a week after wheat midge has come out. If you’re a little bit late, go to your field, take a sweep net, and you can find these little black specks running around against the white background of the net– during the daytime you’ll see them searching on wheat heads as well. And remember that last year’s wheat field is probably this year’s canola field, so it’s another reason to stay out of flowering canola with your sprayer full of insecticide – because you might be wiping out Macroglenes as you’re spraying your canola. They will come out in last year’s wheat field, nectar in the canola, and then will move into wheat to go after wheat midge for you. Up in the Peace River Region, we started studying this, and we actually had fields with pretty much 100 per cent parasitism by this parasitoid on wheat midge.

Cereal aphids

I can never step away from talking about cereal aphids. Aphids are literally born pregnant, and they’re all female, so there’s no egg period. They just drop out and they tap into the phloem and they start feeding, so your aphid populations can increase exponentially unless you’ve got a beneficial insect that acts on them. An aphid can produce two to seven live clones per day, and about 60 in her lifetime. And within about seven or eight days, those babies can start having their own babies.

Cereal aphid.

We have three cereal aphids to worry about. The English grain aphid, the greenbug, and the bird cherry-oat aphid. They can cause honeydew issues. They basically poop sticky sugar, which can get mouldy and cause problems for the crop. They can also transmit viruses like barley yellow dwarf virus. And they of course they suck on the phloem and affect yield directly that way.

Our economic threshold for cereal aphids is 12 to 15 aphids per head, but that’s an average. If you have one head with 60 and you have 20 heads with zero, you are not at your threshold yet. You need to get out there and count 50 to 100 heads per field, and then take the average.

Originally, we used a conventional action threshold where if we get to that economic threshold of 12 to 15 per head you would spray. Now we are using a dynamic action threshold that takes the beneficial insects in the field into account. It uses an equation that predicts the number of aphids eaten by these beneficials. We have an app for that, the Cereal Aphid Manager app. This is free on the Apple and Android systems, and we released it in March 2018. This was a big project of mine.

Pea aphids

I’ve been working on pea aphids lately. We have a good economic threshold for peas at nine to 12 per sweep at flowering. But lentils is a nominal threshold. “Nominal” means “anyone’s best guess” and is 30 to 40 per sweep. So we are working on a threshold for lentils. Until we started working on it, science had absolutely no idea what pea aphids were doing to fababean. No one had done any research on it before.

In conjunction with Sean Prager at the University of Saskatchewan and Ningxing Zhou, a master’s candidate, we are looking at improved management of pea aphids in Saskatchewan pulse crops.

In this research, we are actually counting individual lentil plants. My summer student Haroon Andkhoie doesn’t hate me yet, but I’ve been getting him to count aphids on individual plants. Another summer student figured out that one cup holds 38,000 pea aphids. There is an actual economic threshold down in the United States where they use quarter cups, half cups, and full cups of aphids, so I wanted to know how may aphids they actually had.

Aphid parasitoids emerging from aphid mummies.

Our research on fababean is looking at a cumulative aphid density. That is the number of aphids on the plant and how long they’re on that plant for. At our first density fairly early on, we would reach that density and then spray. By our third, fourth, fifth density the aphids had overwhelmed the plants and we had huge yield losses. There were no pods on density 4. I think that the lack of pods in fababean was due to the aphids just stressing the plants out and they aborted their flowers.

Lentil research was basically the same as fababean. With insecticidal treatments at our first two densities, we get some yield, but no yield at the three later densities. So what we need to do in the future is look more at thresholds in the early spray timing and completely forget about those really high aphid densities later on, because obviously lentils and fababean cannot handle really high populations – they have to be sprayed earlier. Crop staging is likely a major factor.

Aphids have parasitoids, too. The larva develop inside an aphid and create dead aphid mummies that are stuck to plants. These are great visual cues to say, “Hey, you’ve got parasitoids active in your field.” Aphidius spp. create brown mummies and Aphelinus spp. create flat black ones. After the parasitoid lays an egg in the aphid, about 10 days later you get these aphid mummies and then five days after that parasitoid wasps emerge. These wasps attack other cereal aphids and start the cycle over again.

For pea aphids, there is also a different genus of parasitoids, the Praon. Instead of staying inside the mummy, the larva crawls out underneath the aphid and it pupates underneath this now-empty aphid-mummy.

Not all wasps are “beneficial.” Pteromalus venustus is a little wasp that is not beneficial because it goes after alfalfa leafcutter bees. Another parasitoid, Dinocampus coccinellae attacks ladybeetles. This wasp lays an egg into the ladybeetle, and also leaves behind a virus that becomes active as soon as its offspring is ready to crawl out. It paralyzes the ladybeetle when the larva crawls out from underneath it’s wings, and then it pupates between the legs of the ladybeetle as the ladybeetle gently hug its parasitoid that has just crawled out of it.

Dinocampus coccinellae are all female. They can emerge from a ladybeetle and lay an egg right back into that ladybeetle. The ladybeetle is alive and still kicking, but still paralyzed.

There are other wasps that we don’t like and they are called a “hyper-parasitoid.” They will lay an egg into a parasitoid that’s inside the mummy. So we’ve got wasps that attack the wasp inside the aphid, and these guys are not our friends. Dendrocerus bicolor and Asaphes suspensus are two hyperparasitoids that are not beneficial.

Predators of pea aphids

Predators eat other insects. The hoverfly larva is “aphidophagous” and that means, “I eat aphids.” That’s basically all the hoverfly larva does. They’ll take out about 12 aphids a day.

Also associated with pea aphids is the soft-winged flower beetle (Collops). They look like a cereal leaf beetle, so you have to look at the different patternings and what they’re doing. When you see this beetle associated with pea aphids in a pea crop, it’s probably not a cereal leaf beetle because it’s in a pea crop. These soft-winged flower beetles can eat about 54 pea aphids a day.

We’re also finding soft-winged flower beetles associated with Peritrechus convivus. Back in 2017, we just called this “the Twitter mystery red bug.” We had it identified by experts in Ottawa and we identified it by genetic barcoding, and the name of the genus is “dirt-coloured seed bug.” The nymphs are red while the adults are actually coloured like dirt. This insect has been bringing up more questions than answers. We didn’t have any funding to look more into these questions, so I just went out, looked at a few fields, and brought some to the lab.

What I can tell you about these red bugs is the literature suggests they like to hang out in the edges of sloughs. During our drought years, we often plant into the sloughs. So there’s a good chance that we’ve planted crops right into those slough edges, and now we’re seeding in their territory.

This is one of those insects that we just don’t know when it’s going to become a pest and why it’s becoming a pest. I’ve seen them go after flax, canola, and soybean – whatever is there. After it rained though, they stopped feeding on the plants, so it might just be a drought trigger, because there’s nothing else for them to get water from, and that’s why they are feeding on the plants.

Bertha armyworm

Bertha armyworm goes in cycles. Prairie Pest Monitoring Network monitors them with a pheromone trap so that we can let growers and agrologists know if populations are building up. They get attacked by Banchus flavescens, this amazingly big and orange parasitoid. Bertha armyworm also gets attacked by flies that parasitize them.

Calosoma eats bertha armyworms. Photo courtesy of AAFC Lethbridge.

Predatory ground beetles will also attack bertha armyworm. Bertha armyworms, if found on the ground, will get torn apart by ground beetles. Pterostichus melanarius is an introduced ground beetle from Europe, and it, other ground beetles and a few species of rove beetle might also attack bertha armyworm.

Calosoma species, another ground beetle, actually has the common name “caterpillar hunter,” and eats bertha armyworms. If it’s got big eyes that are forward-facing, you know it’s a predator. These guys are excellent predators, and most of our insecticidal sprays will leave the ground that they’re running across toxic to them for about a week afterwards. These ground beetles are kind of the unsung heroes in your field.

Diamondback moth

Diamondback moth is another pest that blows in, so we also use pheromone monitoring traps. If they come in early, we can have problems on the canola. They get attacked by a lot of different parasitoids though. Diadegma semiclausum is one that lays its eggs inside a diamondback moth larvae.

Ladybeetles also eat diamondback moth larvae. If you have ladybeetle larvae in your field, you want to scout for whatever they’re eating, because mama ladybeetle won’t lay eggs in a field unless there is something for her offspring to eat.

In the dynamic action threshold for cereal aphids, adult ladybeetles are eating about 50 to 80 aphids per day, which is pretty good, and their larvae will eat about 70 per day.

7-spotted

ladybeetle larva.

Green lacewings are green and have wings that look like lace. Their larvae are commonly called aphid lions. If you’re sweeping and you find one of the adults in your sweep net, the first clue that you have a green lacewing will be the smell. They release something that smells really bad, because it doesn’t want you to eat it. In the dynamic action threshold, their larvae will take out about 30 aphids per day, and they leave behind the dried husk of an aphid. Their big mandibles inject a digestive enzyme that liquefies the inside of the aphid, and then it sucks out the digested insides like an aphid milkshake. It takes about 15 minutes or so to eat an aphid. For a cabbage looper, the green lacewing larvae takes about one hour to suck out all the juices.

Another one that uses this piercing and injecting of digestive enzymes is the minute pirate bug. Around Saskatoon, we get Orius tristicolor and in Eastern Canada they have Orius insidiosus. It’ll eat about 12 aphids a day, but it will also eat things like diamondback moth eggs.

Damsel bugs are like a little praying mantis, with raptorial front legs. They have a long beak, and they will also inject digestive enzymes.

Spiders are also predators, although they aren’t ‘insects’ because they have eight legs.

Some spiders build webs in your fields, and others run around on the ground eating insects. Their impact is kind of understudied in Canada right now. “Daddy longlegs” or “harvestmen” are not quite spiders but have these huge fangs that they use to capture their prey.

Wheat head armyworm

Wheat head armyworm has started to show up. You often don’t know that you have a problem in your field until you go to swath it, and you see a mess of them on your cutter bar.

This insect will attack barley and wheat. One can take out an entire wheat head in one day. It has two generations in one year. If parasitoids don’t take out the first generation, you can get a buildup into the second generation that continues the damage.

We don’t usually have too much in the way of issues, though, because it’s got a pretty good parasitoid, a Cotesia species. You may see the pupae of Cotesia in white clusters on the awns of the heads of cereal crops. The wasp lays an egg in the wheat head armyworm and the egg splits multiple times before each cloned egg hatches inside the armyworm. The genetically identical female Cotesia larva all emerge at the same time from the one egg that has split inside the caterpillar. As soon as they come out, they start making their cocoons and you get these Cotesia clusters in the field.

Flea beetle

The two main flea beetles that are attacking canola are the crucifer and the striped that is moving down from the north. When you’re scouting, you want to look for 25 per cent damage – that is the action threshold. If it’s a hot day, by the afternoon that plant can be at 50 per cent damage, which is where we see yield losses in canola.

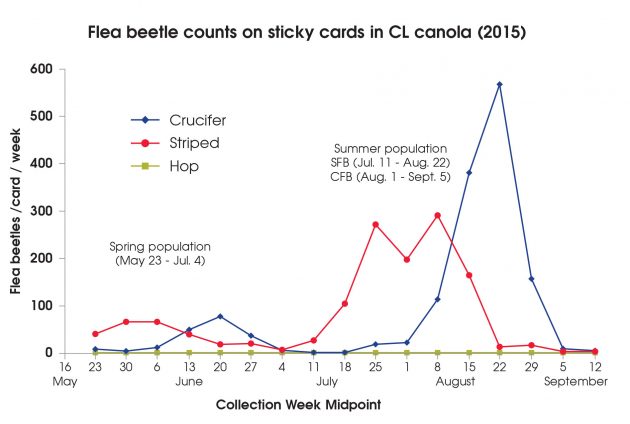

We have two generations of flea beetles, so you’re going to see them coming back into the field in the fall for the “overwintering generation.” Conventional wisdom used to be to plant early to escape flea beetles because the crucifer didn’t peak until mid- to late-June. But the striped flea beetle peaks before the crucifer flea beetle. So now we have a longer period of flea beetle feeding from mid- to late-May through late June.

I’ve had the question of whether there were just more flea beetles in 2019. I compared the number of flea beetles collected on sticky cards in my plots at Saskatoon in 2018 to 2019. The answer was yes, there were a lot more in 2019. If we look back 10 years ago, they would have been mainly crucifer, but the striped has really been taking over recently. The second generation will come back in the fall, and they’ll feed on anything that’s green. If it’s nothing but pods, they will feed on pods, and they can cause debarking, and this can lead to pod shatter. But none of the research has indicated that this is economical damage at this point in time.

Microctonus vittatae parasitizes flea beetles, but unfortunately this parasitoid doesn’t do a really great job. It has only 2.5 to 5 per cent parasitism rate, which is not enough to control populations.