Features

Agronomy

Plant Breeding

Breeding for very early maturing soybeans

Soybean breeders have been making great progress in developing early varieties for the Prairies, and even shorter season varieties are in the works.

October 20, 2014 By Carolyn King

Soybean variety trials at the Canada-Saskatchewan Irrigation Diversification Centre at Outlook Expanding soybean production to the west and north of southern Manitoba requires shorter season varieties that still produce good yields.

Soybean variety trials at the Canada-Saskatchewan Irrigation Diversification Centre at Outlook Expanding soybean production to the west and north of southern Manitoba requires shorter season varieties that still produce good yields.Expanding soybean production to the west and north of southern Manitoba requires shorter season varieties that still produce good yields. Soybean breeders have been making great progress in developing early varieties for the Prairies, and even shorter season varieties are in the works.

“With the interest in growing soybeans in Manitoba at over a million acres in 2013 – and we’re expecting that to grow in 2014 – and the increasing interest in Saskatchewan and even Alberta, we’ve seen a need to push for even earlier maturing soybeans,” explains Dr. Elroy Cober, a soybean breeder at the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Research Centre in Ottawa, Ont. One of his current breeding projects aims to develop very short season varieties.

Developing such varieties involves selecting for several characteristics. “Soybeans are a short-day plant. That means they flower fastest under short days, and as the days get longer their flowering and maturity time are slowed down,” says Cober. “As we move north in Canada, we’re moving into longer and longer day lengths during the summer, so we need soybeans that are less sensitive to those longer days.”

Cober and other researchers are working to identify the genes that influence when a soybean plant reaches maturity. So far, 10 genes have been identified and all are related to day-length response. “Often, for each gene, there is an early maturity version and a late maturity version. The late version makes the plant responsive to day length,” he notes. “So we need to [develop lines that] accumulate the early versions of those genes.”

The cooler temperatures in northern regions are another consideration. “Soybeans need to have soil temperatures around 9 or 10 C before they will germinate, so that limits how early you can plant in the spring. Late spring frosts can be an issue,” says Cober. “Cool temperatures can also be a problem during flowering time. If temperatures drop below 10 C at night, it can cause the flowers and pods to abort and drop off.” Again, it’s a matter of selecting lines better able to tolerate cooler temperatures.

Dr. Steve Schnebly, senior research manager for soybeans at DuPont Pioneer, and Don McClure, a soybean breeder for Syngenta, see the same key considerations in developing soybean varieties suited to Prairie latitudes and temperatures.

“When we push the boundaries of the soybean production area further west and north, we’re really pushing the limits of adaptation of soybeans,” says McClure.

“Maturity is so critical, and the early maturities are a particular challenge because if we push the maturity too early, then the yield really suffers. So it’s trying to find that balance. They have to mature for sure, but they also have to have competitive yields. The bottom line for the grower is that soybeans have to be competitive [in terms of profits] with other Prairie crops like canola and wheat.”

Rapid advances

“The Canadian Prairies are the new frontier for soybeans. With the success in Manitoba, soybean breeding companies are looking westward,” says Garry Hnatowich, research agronomist with the Irrigation Crop Diversification Corporation at Outlook, Sask.

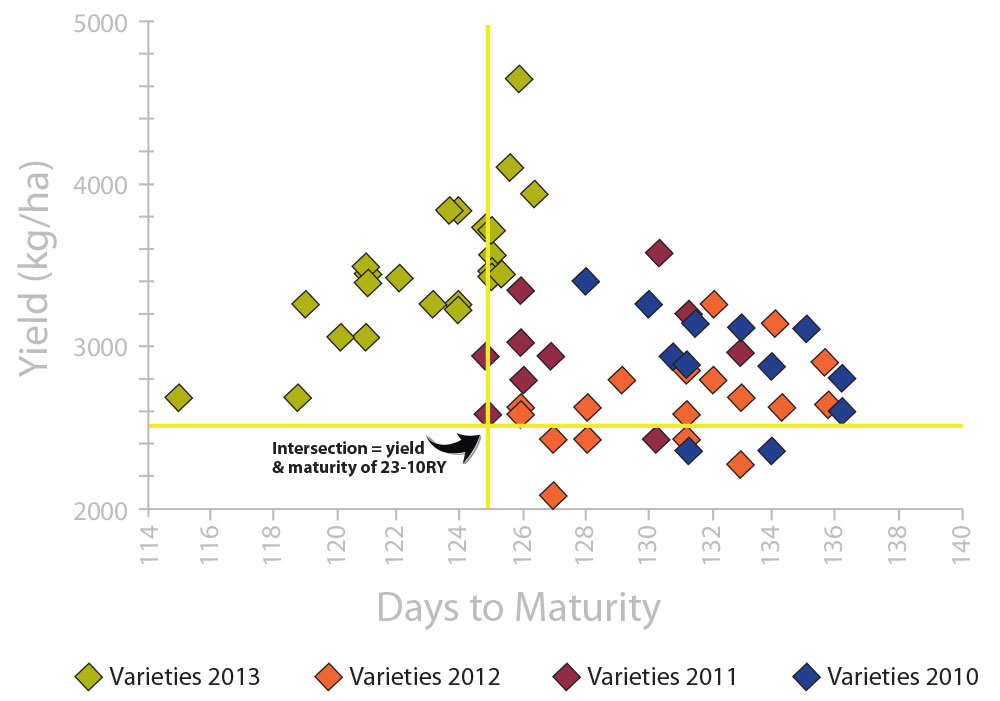

For about the last decade, Hnatowich has been testing a wide range of soybean varieties at the Canada-Saskatchewan Irrigation Diversification Centre. Over the last four years, he has seen an influx of much earlier maturing varieties in the testing process for varietal registration. For instance, in 2010, the varieties he tested had days to maturity ranging from 128 to 136; by 2013, they ranged from 115 to 126 (see Fig 1).

|

| Fig. 1: Yield versus maturity for soybean varieties tested at Outlook, Sask., 2010 to 2013. Source: Irrigation Crop Diversification Corporation.

|

Hnatowich speculates, “Such a rapid influx of early maturing varieties suggests to me that perhaps the powerhouses in soybean breeding had some early maturing lines originally targeted for the Dakotas and Minnesota that didn’t meet needs of those areas, so the lines were shelved. I think they may have dusted off some of those lines to see if they have a fit in places like Saskatchewan.”

Until 2014, the maturities of most soybean varieties for the Prairies were rated based on heat units. However, heat units aren’t the best tool because day length is such a key factor. So, soybeans in the U.S. and increasingly in Canada are classified using a maturity group system based mainly on day length, but also influenced by temperature. In North America, the groups range from X in Mexico, to IX in southern Florida, and so on northward to 00 in northern Minnesota and southern Manitoba, to 000 into western Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

Within each group, relative maturities are assigned, ranging from 1 for the earliest to 9 for the latest. For instance, in the double zero group, the earliest would be 00.1. The seed company determines the ratings for its varieties by growing them in various areas and seeing how they perform compared to standard varieties; sometimes a variety’s rating changes somewhat over time.

Soybean seed companies already have some good short season varieties for the Prairies. For example, Syngenta’s Don McClure says, “We’re making specific crosses with specific parents that we think will work well on the Prairies. We are testing our very earliest material at multiple sites there to gain insight into its ability to cope with western Canadian conditions. We have really bumped up our testing efforts in Western Canada and we have plans to continue that.”

McClure highlights two double zero varieties from Syngenta. “S007-Y4 is our earliest current variety. It would be classed as a mid-season variety in southern Manitoba; it’s around 2400 heat units, maybe even a bit earlier than that. In the Manitoba public trials, it was one of the top yielders for its maturity. We’ve had seed production there for two years now and both years it has yielded really well in seed fields,” he says.

“S00-T9 would be considered a full season variety in southern Manitoba. Its performance has been outstanding the last two years, with excellent performance in the Manitoba public trials.”

He adds, “We have some very early maturity material in our pipeline, some nice material that is significantly earlier than S007-Y4 and S00-T9.”

DuPont Pioneer has really increased its focus on soybeans for the Prairies over the last seven years. Schnebly explains, “Initially, a lot of the breeding occurred out of our Moorhead, Minnesota station, and then we would bring materials up into the Carman [Manitoba] area to do some local testing.” In 2011, the company started testing early generation material at its Carman facility. More recently, DuPont Pioneer has expanded its Carman facility and extended its soybean yield testing trials across Manitoba. It has plans to further expand the facility and hopes to start Saskatchewan soybean trials in the coming years.

Schnebly points to two very short season varieties resulting from this breeding effort. “Until the last couple of years, we’ve focused on mid and late double zeros, but in the last year we have released two new lines that I believe set a new benchmark in terms of maturity for the industry in Manitoba and the west.

“Those are P001T34R and P002T04R. They are very early double zero lines, almost bordering on triple zero. P002T04R really performed well last year and we have a lot of expectations for that line in 2014 and beyond.”

And he notes, “We have triple zero experimental lines in our pipeline, and they are in the process of being tested. I think in a few short years we’ll be seeing some exciting developments in triple zeros as well.”

A few triple zero varieties are currently available, such as Pekko R2, developed by Elite, and NSC Moosomin RR2Y, from NorthStar Genetics.

Developing even earlier varieties

In Cober’s project to develop very short season soybeans, he is tackling the issue of the yield penalty associated with the long day lengths on the Prairies.

To illustrate this problem, he describes the results of a study by AAFC plant physiologists, who grew 10 soybean lines at both Ottawa and Morden, Man. “At Ottawa, on average, the lines spent a third of their life in the vegetative growth, then they flowered and spent two-thirds in reproductive growth. At Morden, it took half of their life until they started flowering.”

So, at Morden, the varieties spent less time in flowering and seed filling. “I think this may be causing lower yield potential at Morden,” says Cober.

He hopes to get around this problem by doing very early generation selections in the longer day-length environments at Saskatoon and Morden. “So I make the cross, I do a generation advance, and then we send the populations, completely unselected, to Saskatoon and Morden. They make selections there and then do the yield trials,” Cober explains. He is collaborating with Dr. Tom Warkentin at the Crop Development Centre in Saskatoon and Dr. Anfu Hou at AAFC’s Morden Research Centre in this project.

“Up until now, all of the soybean varieties grown in Manitoba have not been selected in Manitoba at early generations. The material is coming from Quebec, Ontario, Minnesota or North Dakota, so they are varieties that were initially selected in more southerly locations, then tested in Manitoba, and the best of those are being grown in Manitoba,” says Cober.

“But if we actually started from the very beginning, doing the very earliest selections in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, could we make even more improvement? That’s the question we want to test in this project.”

This five-year project, which started in 2013, is funded under Canadian Field Crop Genetics Improvement Cluster, which is led by Canadian Field Crops Research Alliance. The Manitoba Pulse Growers Association (MPGA) is also providing some funding.

MPGA’s interim executive director, Francois Labelle, says, “We’ve seen the migration of the soybean growing area from the middle U.S. into the northern U.S. and southern Manitoba, and then into western Manitoba and Saskatchewan. That requires shorter season varieties, and Dr. Cober is doing work to develop those varieties that will give us good yields and so on.

“Soybeans are an exciting crop to add to the rotational mix,” he adds. “They offer a number of advantages to growers, but overall, at the end of the day, it is a matter of economics, that growers can make money with the crop.”

Prospects for expanding soybean acres

Soybean production on the Prairies has been increasing rapidly. According to Statistics Canada, the area seeded to soybeans in Manitoba grew from 520,000 acres in 2010 to an estimated 1.3 million acres in 2014. Statistics Canada started reporting soybean production for Saskatchewan in 2013. Soybean acres were at 170,000 acres that year, and increased to an estimated 300,000 acres in 2014.

In 2013 the average soybean yield was 37.6 bushels per acre in Manitoba and 27.2 in Saskatchewan. According to Hnatowich, yields were pretty good in the Lake Diefenbaker area in 2013. “Dryland soybeans in the area were about 35 bushels and the irrigated were about 45, so the potential certainly showed.”

Adds McClure, “I think the soybean acres in Western Canada will continue to expand. We have good early soybean varieties that yield very well and perform consistently on the Prairies, and growers are making money growing soybeans. Also, soybeans are a legume, so they are a great rotational crop for wheat. And growers can use exactly the same equipment they already have to grow cereals and canola. Soybeans are a good fit on the Prairies and will continue to grow in popularity as we get more variety choice for the growers.”

Schnebly says that at least two major things have to fall into place for expansion of soybean acres in Western Canada. “You need a good base of genetics, and you need a solid agronomic program for customers to be profitable. That’s something we have seen develop extremely well in Western Canada over the last four years; it’s been amazing to me to see the crop change, with the combination of our Pioneer agronomists working with our customers to get maximum yield. I see a very bright future as we look to develop soybeans for the western Prairies over the next five to 10 years.”

McClure believes an important factor in the expansion of the soybean growing area is moderating climatic conditions. “We’re getting a little longer seasons in Western Canada and a little more consistent rainfall. This is a trend we’ve seen over about the last 20 years, as the Corn Belt in the U.S. has been moving north from around Iowa and Illinois into Minnesota and South Dakota, then into North Dakota and then Manitoba. And now it’s moving further west.”

Hnatowich has noticed the benefits of a longer growing season for soybean production in recent years. “Over the last three or four years, we’ve had wide open falls in Saskatchewan, and that has certainly contributed to successfully getting the varieties off the field.” However, he’s worried that fall weather patterns will return to the historical norm of early-September frosts.

“With some of the varieties we have now, we would harvest something, but we would not probably be expressing their full yield,” says Hnatowich, adding that he still views soybeans as a risky crop for Saskatchewan. “But I think the potential is there, and I know the breeding effort that is going into soybeans … So I think it is only a matter of time before we see varieties that both yield a profitable return for Saskatchewan conditions and have the likelihood of maturing nine years out of 10.”