Features

Agronomy

Insect Pests

Adjust bertha armyworm thresholds based on crop prices

When canola prices increase, it takes fewer insects to reach economic threshold levels.

November 23, 2007 By Bruce Barker

In 2007, bertha armyworm larvae reached the thresholds for spraying in some areas of the prairies, including parts of northwestern, southwestern and central Manitoba and central Saskatchewan and southern Alberta near Vulcan. What that means for 2008 is that growers in all areas affected by bertha armyworms in 2007, as well as areas reporting bertha armyworm moth activity next year, should scout for their emergence and development and be prepared to assess economic threshold levels.

In 2007, bertha armyworm larvae reached the thresholds for spraying in some areas of the prairies, including parts of northwestern, southwestern and central Manitoba and central Saskatchewan and southern Alberta near Vulcan. What that means for 2008 is that growers in all areas affected by bertha armyworms in 2007, as well as areas reporting bertha armyworm moth activity next year, should scout for their emergence and development and be prepared to assess economic threshold levels.

“We know the potential is still there for 2008. Bertha armyworm tends to go in four year cycles in an area, so we are still anticipating some infestations next year, especially in those areas that were seeing populations cycling up,” says David Vanthuyne, Canola Council agronomist at Watrous, Saskatchewan.

The bertha armyworm life cycle has one generation per year. Adult moths emerge from overwintering pupae in mid June and emergence continues until late July. Adult moths mate within five days of emergence and lay their eggs on the undersides of canola leaves soon after emergence. The eggs are laid in single-layer clusters of 50 to 500 in a honeycomb arrangement. Each female moth will lay about 2150 eggs but as many as 3500 eggs per female have been recorded. At average temperatures, the eggs hatch within a week.

Newly hatched larvae are about 0.3cm (0.1in) long. They are pale green with a pale yellowish stripe along each side. Due to their size and colour, they are difficult to see on the undersides of leaves. When disturbed, small larvae may drop off the leaves by a fine silken thread.

John Gavloski, extension entomologist with Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Initiatives (MAFRI) at Carman, says this behaviour makes it difficult to distinguish small bertha armyworm larvae from those of the diamondback moth, which have a similar behaviour.

Large larvae drop off the plants and curl up when disturbed, a defensive behaviour typical of cutworms and armyworms. When scouting for larger larvae, Gavloski recommends shaking plants in an area to knock larvae that may be on the plant to the ground; then count larvae on the ground. Look under debris and in cracks in the soil. Larger larvae may vary in colour; some may remain green, but many may become predominantly brown or black. Larvae are about 4.0cm (1.5in) long when fully grown and will have a broad, yellowish-orange stripe along each side.

Control for bertha armyworm occurs at the larval stage, usually when the larvae begin feeding on the pods. Research has found that there is little measurable economic loss due to bertha armyworm until pods are damaged. The ideal spray timing is when larvae just begin to feed on the pods. Gavloski explains that aside from direct seed losses that can be caused by larvae feeding on the pods, seeds from damaged pods have a greater proportion of green and broken seeds causing lower seed grade.

Vanthuyne says the most important consideration for spray applications is observing insecticide pre-harvest intervals. Pre-harvest interval is the number of days that must pass between the last application of a pesticide and swathing or straight combining of the crop. “Some of the insecticides can be applied seven to 10 days prior to swathing, but others are up to a 21 day pre-harvest interval,” cautions Vanthuyne.

Lower thresholds with increased canola prices

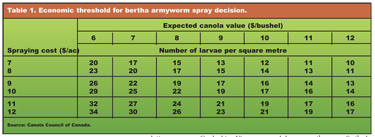

Perhaps the biggest change for canola growers when considering economic thresholds was the higher price of canola in 2007. As prices go up, it takes fewer larvae to pay for the cost of the spray. Research has shown that the loss due to bertha armyworm will be approximately 0.058 bushels per acre for each larva per square metre. Gavloski explains that when the larvae can be controlled for less than the value of the crop lost, then it makes sense to spray. If the cost of control is higher than the loss due to the larvae, then it makes sense not to spray.

For example, when canola was $6 per bushel, it would have taken 26 larvae per square metre to pay for a $9 per acre spray cost. With canola at $8 per bushel, the economic threshold would have dropped to 19 larvae per square metre.

The other wildcard for some growers in 2007 was a dual infestation of bertha armyworm and diamondback moth. In fact, Vanthuyne says bertha armyworm spraying was likely under-reported because growers were targetting diamondback moth. As a result, he believes that earlier bertha armyworm larvae stages were controlled with the diamondback moth spraying, so they were not able to develop into the more noticeable mature larvae stages.

Vanthuyne says that in some cases, there were 15 to 20 diamondback moths per square foot along with bertha armyworm. “When you have dual infestations, you should drop your thresholds by 20 percent when making a spray decision,” he explains.

End in sight?

Gavloski explains that a combination of parasites, predators, viruses and fungi can reduce and regulate numbers of bertha armyworm. The two most constant parasites regulating bertha armyworm are a wasp called Banchus flavescens and a fly called Athrycia cinerea. Parasites can kill up to 75 percent of bertha armyworms. Unfortunately, larvae are often not killed until after they have damaged the crop. Parasites decrease feeding by bertha armyworm larvae and can cause significant decline the following year.

“It is important to only spray when economic thresholds warrant, or you will be killing the beneficial predators as well,” explains Gavloski.

Viral and fungal diseases of bertha armyworm can be common under some conditions and also contribute to a sudden decline in bertha armyworm populations, says Gavloski. Virus infected larvae appear melted onto the plant. A fungus, which affects the late instar larvae, belongs to a group of fungi called Entomophthorales, which are predominantly insect pathogens. Affected larvae often turn a lighter brown colour just before they die. Dead larvae are light beige to a white colour and are frequently found attached to canola foliage. They are dry and brittle, often breaking apart when handled. High rates of mortality (50 to 75 percent) have been observed when epidemics occur. Wet conditions may result in increased mortality due to this fungus.

Obviously, these natural control mechanisms will not eliminate bertha armyworm forever – after all, bertha armyworm has been a cyclical pest of canola almost from day one in Canada. However, natural control partly explains why bertha armyworm cycles up and down over the years. So the best advice for 2008 is to scout crops in the spring and observe economic threshold levels when making spray decisions.