Features

Agronomy

Soybeans

Managing glyphosate resistance for soybean success

From humble beginnings, soybean acreage hit 2.3 million seeded acres in Manitoba in 2017. Can those acres be sustained? The answer lies with managing glyphosate resistance.

March 23, 2018 By Bruce Barker

Waterhemp seed heads vary in colour from dark to light red. From humble beginnings

Waterhemp seed heads vary in colour from dark to light red. From humble beginnings

“We really need to learn from farmers in the United States who are already dealing with glyphosate resistance. Their narrow crop rotations of Roundup Ready corn and Roundup Ready soybean have selected for glyphosate-resistant weeds. Those two crops are not a crop rotation,” says Ingrid Kristjanson, farm production extension crops specialist with Manitoba Agriculture.

In North Dakota and Minnesota, weed scientist Jeff Stachler tracked the development and expansion of glyphosate resistant weeds. In 2006, glyphosate resistant giant ragweed was identified in one county in Minnesota. In 2007, common ragweed in North Dakota and waterhemp in Minnesota were added to the list. By 2013, glyphosate resistant horseweed/marestail and kochia were also confirmed. Throughout the Red River Valley, glyphosate resistance is widespread. Kirk Howatt with North Dakota State University says in 2017, waterhemp is more prevalent within the area designated in 2013, but has expanded very little. Other glyphosate resistant weeds are similar to the areas Stachler identified.

The situation isn’t as challenging in Manitoba. Glyphosate resistant kochia was identified in 2013, and by 2016 was found in five rural municipalities in Manitoba. A case of glyphosate resistant waterhemp was also detected in the Eastman area of Manitoba in 2016.

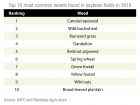

A 2016 weed survey identified the most common weeds found in Manitoba soybean fields. These weeds included some of the ones most likely to develop glyphosate resistance, which have been identified by weed scientists as wild oat, green foxtail, wild buckwheat and cleavers.

While Manitoba seeded acreage and crop rotations aren’t the same as the corn-soybean rotation in the U.S., about 40 per cent of Manitoba seeded acreage may be seeded to Roundup Ready crops – putting large selection pressure for glyphosate resistance. In addition to the 2.3 million acres of soybeans, another 410,000 acres of corn and 3.1 million acres of canola bring seeded acreage of those three crops to 5.8 million acres. Given that canola acreage also includes Liberty Link canola, and some conventional corn and soybean is still grown, the seeded acreage of Roundup Ready crops might be around four million acres of the 10 million acres of Manitoba land in annual crop production.

“If you grow more glyphosate-resistant crops, you are increasing the selection pressure for glyphosate-resistance,” Kristjanson says. “Glyphosate is a tremendous tool, but we need to manage it properly.”

Know the risk

In order to slow the development of glyphosate resistant weeds, Kristjanson says that farmers should understand their own risk. While some of the glyphosate resistant weeds may move north up the Red River Valley during flood years, or be transported by feed or waterfowl, the biggest management impact can be made on individual fields.

“Yes, the risk is there for resistant weeds to move in from other areas, but we can’t be blind and blame someone else. Anything you can do to expand the use herbicide groups and mode of actions, along with longer crop rotations will result in less selection pressure,” she says.

Kristjanson says an important starting point is to scout fields both before and after herbicide applications and to maintain records of herbicide use in order to better rotate modes of action. For kochia, if a resistant population is suspected, Manitoba Agriculture’s Pest Surveillance Initiative offers an in-season qPCR (quantitative polymerase chain reaction) analysis to confirm glyphosate resistance for $125.

Weed patch management can help hold back resistant populations once they are established. Kristjanson walked the field where glyphosate resistant waterhemp had been reported in 2017 and couldn’t find any additional waterhemp plants. “The farmer had done a tremendous job of roguing the field.”

The prolific nature of waterhemp highlights the need to scout and eliminate patches. An example from Minnesota shows the risk of not keeping on top of weed patches. In 2011, a single water hemp plant produced 142,000 seeds (kochia produces about 15,000 seeds per plant.) Taking a conservative 100,000 seeds from one plant on one acre, if 25 per cent of seeds emerge the following year, 10 per cent of plants are resistant to glyphosate and glyphosate is used again, in 2012 there would be 2,500 plants per acre. In 2013, using the same scenario, 6.25 million resistant plants per acre would be present. Considering that the ideal soybean plant density is 180,000 to 210,000, it is easy to see how soybeans can be quickly overwhelmed if weed patches aren’t managed.

Kristjanson says knowing the weed life cycle can also help manage resistant populations. Kochia seed has low survivability of around one year. By preventing the kochia from going to seed, resistant patches can be managed if plants aren’t allowed to go to seed. A farmer with glyphosate resistant kochia that she visited dealt with the problem by roguing kochia escapes.

“He had done a tremendous job of cleaning up kochia. I went back to his field this year at harvest, several years after the initial discovery, and could only find one kochia plant,” Kristjanson says.

Rotating herbicide groups and using tank-mixes of different herbicide mechanisms of action is a well-worn message, but these strategies are more difficult in short rotations using glyphosate-resistant crops. Kristjanson says Minnesota used to grow a lot of wheat in rotation, but that has dropped off and the result is more glyphosate resistant weeds. Soybean crop diversity can also include Xtend (dicamba and glyphosate tolerant), conventional and non-GM varieties that allow herbicide diversification.

“In Manitoba, we tend to grow a wide range of crops because of our climate. If you start to reduce those cropping options you increase your risk,” she says. “We talk about a mixture of cool/short season crops and warm/long season crops as helping to keep weeds off-balance. Introducing winter wheat and fall rye adds another dimension to delaying resistance.”

Soybeans are slow to establish and grow, resulting in greater weed pressure and more emphasis on herbicide applications. Ensuring a good plant stand with high seeding rates and narrow row spacing can help with weed competition and improve herbicide performance.

Putting all the pieces together requires a weed management strategy and crop rotation plan. Certainly, market reality plays a role, but short-term gain from short rotations comes with a cost of reduced herbicide options in the future.

“It is really important to keep your options open by using practices that reduce selection pressure. Farming is hard enough without herbicide resistance.”