Features

Pulses

Pulses show promise for Eastern Canada

Pulse research is expanding the rotation options for Atlantic farmers.

February 15, 2019 By Julienne Isaacs

Ag Canada research scientist Aaron Mills is leading a study in pulse growing options for Atlantic Canada. PHOTO COURTESY OF AARON MILLS.

Ag Canada research scientist Aaron Mills is leading a study in pulse growing options for Atlantic Canada. PHOTO COURTESY OF AARON MILLS. It was during a 2013 vacation to Prince Edward Island, where Chris Chivilo grew up, that he and his wife, Tracey, had the idea to support the development of the pulse industry in Atlantic Canada.

“Looking around, some of the crops hadn’t been grown when I was raised on P.E.I., such as grain corn and soybeans,” Chivilo says. “Seeing that those crops were doing well, I thought for sure we could grow fababeans, which were hot out west at the time. We’d also started growing them in northern Ontario. We thought, let’s try some on P.E.I. and see if they do well.”

Chivilo is president and CEO of W.A. Grain and Pulse Solutions, based in Innisfail, Alta. With six cleaning and processing plants in Western Canada, the company is one of Canada’s biggest pulse exporters.

Last year, the company opened its $8 million pulse processing plant in Summerside, P.E.I. – the first such facility in Atlantic Canada, and the sole reason producers in the Maritimes can now seriously consider putting pulses in the rotation.

The plant’s establishment followed on the heels of a four-year Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research collaboration study solely funded by the Chivilos to investigate basic agronomy for a variety of pulses on PEI.

Prior to the plant’s arrival, marketing opportunities for pulses were almost nil, according to Aaron Mills, the research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada who is leading the study. “The market opportunities developed by W.A. Grains are what is driving the increase in pulse acres in the region,” Mills says.

Mills had been looking into the development of alternative rotation crops for potato producers since 2011, including pulses, when the Chivilos approached him with an offer to support pulse research on the Island.

“For a lot of these emerging crops, they have fairly established production practices in Western Canada, but it’s totally different in Eastern Canada, so we needed to start with the basics,” Mills says.

Potato rotations

The Maritime Provinces, led by P.E.I., are Canada’s biggest potato exporters. A three-year rotation is mandatory for potato growers on the Island. Mills says a typical rotation used to be potatoes followed by barley underseeded to red clover, with the clover allowed to grow the third year.

But Mills says there’s no typical P.E.I. rotation anymore and notes the emergence of several crops new to the region, including cover crop mixtures, soybeans and pulses. Soybean acres, for example, have jumped from 18,000 acres in 2008 to more than 50,000 seeded acres in 2018.

The reality is that there are few profitable rotation crops for non-potato years, and this is where there is a potential for pulses, says Mills.

Soybeans add economic value to the rotation but very little value to the soil in terms of residue or organic matter. Added to this, soybean yields aren’t high and beans don’t come off the field until late-October or mid-November, when most producers would prefer to have everything put away in the bins.

Disease and wireworm pressure are also growing problems for potato producers across Atlantic Canada. For this reason, interest in mustard as a biofumigant has been increasing, says Mills.

“Wireworm is so terrible that growers are looking for alternative crops that act as biofumigants to control pest populations. Mustard is one of those crops,” he says.

Mustard has traditionally been used as a plough-down crop, but Mills’ team is conducting trials to see if the plant’s biofumigation effects are retained if the seed is harvested. “That way, you can get a crop off and have time to put in another crop of mustard or buckwheat to cover the soil in the winter,” he explains.

Enter pulses, specifically peas, which work well as a rotation crop before mustard, because the pea crop is off the field by the middle of August, leaving time to put in mustard or buckwheat. The same goes for fababeans, although they mature a bit later, says Mills.

His research team is also looking at intercropping mustard and peas, which is commonly done in Western Canada. “One of the classic mixtures that used to be grown on P.E.I. was peas, oats and barley. The new pea-mustard mixture would be another way to keep diversity in the rotation,” Mills says.

Recently, Mills began an AAFC-funded study looking at carryover effects of peas, fababeans and soybean on winter wheat, with a focus on soil health metrics and nutrient carryover.

But the work goes beyond peas and fababeans. During the W.A. Grains-funded project, the team has been working to hammer out the agronomy for chickpeas, lentils, black beans and pinto beans in their field trials. Pulses that perform well in initial field trials are carried over into AAFC projects.

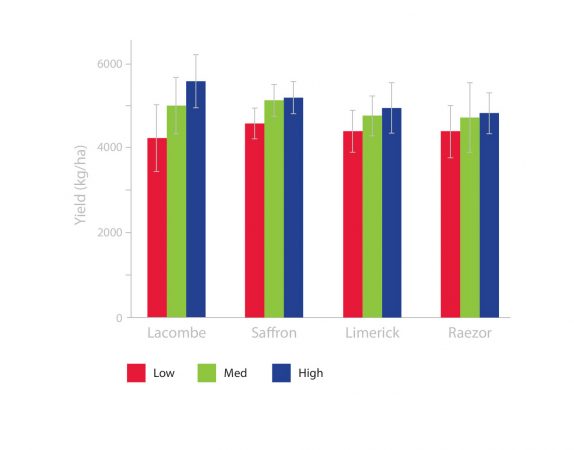

Seeding rate data for the average of the 2017 and 2018. Seeding rate data for the average of the 2017 and 2018 growing seasons. The low, medium and high seeding rates are 75, 100 and 125 seeds/m2 respectively, or 160, 210, or 260 lb/ac; the x-axis shows different pea varieties. Limerick and Raezer are green peas, and Lacombe and Saffron are yellow pea varieties. Courtesy of Aaron Mills.

Challenges and opportunities

Weather conditions present an obvious challenge for pulses in Atlantic Canada. Mills says springs have been getting later in the Maritime Provinces and pulses have been going in the ground later than hoped.

Generally speaking, weather conditions on P.E.I. are more akin to Europe than Western Canada, so Mills’ team is looking into planting European pulse varieties, which can stand up to wetter, temperate conditions better than many varieties developed in the west.

But Mills says his research team’s initial goal was not to evaluate varieties, but rather get a sense of which pulses appear to do well in Atlantic Canada and to generate basic agronomic data, including specific recommendations for plant population, spacing, fertility and herbicide options. Now that they have completed a lot of the development work, they can analyze how specific pulses perform in rotation with potatoes.

Along with peas and fababeans, chickpeas, black beans and pinto beans also show promise. 2018 was unseasonably hot and dry, but the team’s chickpeas and black beans performed well. The lentils were planted too late and did not pod up, and the team ran into harvesting issues with their pinto beans, but Mills says both crops will be planted again in 2019.

Mills says that it is likely that disease will someday become a major issue for pulse producers in Atlantic Canada, like it is in many parts of Western Canada, so they are recommending fungicide application as part of general management practices. “We haven’t seen disease levels high enough to result in economic losses, and the yield data is surprisingly good – in short, we’re in the honeymoon phase here for these crops,” he says.

His team has A-base funding to continue work with pulses until 2021 and plans to do further work on intercropping with pulses in potato rotations.

This year, Chivilo’s Summerside plant took in 10,000 tonnes of peas and beans, a figure they hope will rise by 50 per cent in 2019.

“Farmers want choices, good choices that won’t cost them money,” he says. “I would encourage farmers to look at all the choices and, when it comes to adding pulses into the rotation, weigh the benefits to their land and bottom line.”