Features

Herbicides

Seed & Chemical

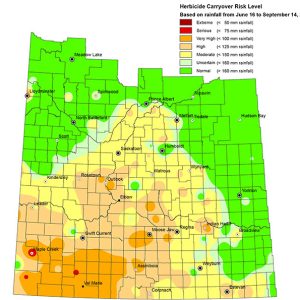

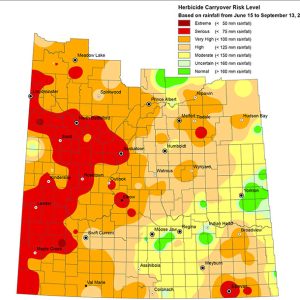

Herbicide carryover considerations for 2022

Examining the potential for herbicide carryover in the 2022 growing season.

June 13, 2022 By Presented by Clark Brenzil, provincial specialist – weed control with Saskatchewan Agriculture, at the Top Crop Summit, Feb 23, 2022.

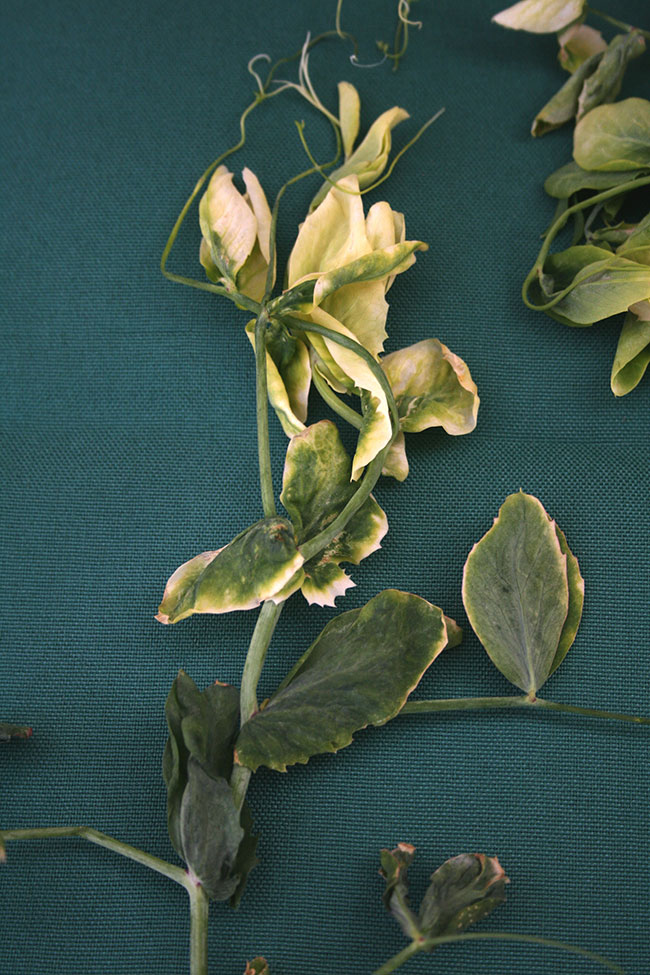

ABOVE: Infinity herbicide carryover damage to pea. Photo courtesy of Clark Brenzil.

ABOVE: Infinity herbicide carryover damage to pea. Photo courtesy of Clark Brenzil. While there are several mechanisms that degrade herbicides in the soil, the two major ones are chemical hydrolysis and microbial activity.

With microbial activity in the soil, a variety of bacteria and fungi use herbicides as a food source, and as living organisms, they need moisture to survive. In a drought year, micro-organisms are not active since they require moist soil to survive. Most of these microbes are aerobic, so breakdown is slower in saturated soils where oxygen is limited. Group 3 herbicides can break down without oxygen, but that is the exception to the rule.

Chemical hydrolysis is where water cleaves the herbicide molecule in half to deactivate it. It requires moisture in the soil, as well.

If there is adequate moisture for breakdown – predictable breakdown under normal conditions – the other component is time. There has to be moisture for an adequate period of time at reasonable soil temperatures.

As a general rule, moisture is required between June 1 and Sept. 1, because this is the period during which there are warm soil temperatures for microbes to be active or for chemical hydrolysis to take place.

The rate of breakdown also depends on the herbicide. Some require six inches of moisture in that time period, while others require four inches of rainfall. If there are fewer than four inches, it is safe to say that all herbicides that normally carry over will be further affected by the lack of moisture. With rainfall amounts greater than six inches, generally there is relatively predictable herbicide breakdown.

The risk of injury from a herbicide depends on the herbicide and the crop that might be affected. On page 89 of the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture’s 2022 Guide to Crop Protection, there is a chart of herbicides and their carryover restrictions under normal conditions. These are the herbicides most at risk of carrying over and causing crop damage under low moisture conditions.

Some herbicides have multi-year recropping restrictions as well. If there were environmental conditions like the very dry conditions of 2021, add an extra year on to the recropping restrictions for every year with low rainfall.

For example, if a herbicide with a two-year recropping restriction was applied in 2019 with reasonable breakdown in 2019, but dry conditions occurred in 2020 and 2021, no breakdown may have occurred in those years. Essentially, what was a two-year breakdown window is now a four-year breakdown window.

Also, look at rainfall in that three month period. Rainfall in the shoulder seasons can be deceptive because temperature is very important for breakdown, as well. Rainfall that occurs in the fall, following a summer drought, may not allow for adequate breakdown.

As a general rule, if crops looked reasonably healthy in the previous growing season in the absence of a reserve of subsoil moisture, then there probably won’t be a lot of unexpected carryover going into the next year. But if crops were showing

symptoms of drought, that would be a good indicator that herbicide carryover may be a risk. There are also situations where there is good amount of subsoil moisture that keeps the crop doing well, yet there is insufficient surface moisture to promote breakdown. 2017 is a good example of that kind of year.

The top tip is to be really conservative with your crop choices for 2022. This is not the year to push the envelope for tolerance to herbicide carryover. This is the year to be very, very conservative for the crops being chosen, even within the recommended options. These crops may not be the most lucrative, but will be the ones that can provide a return.

Work with the manufacturer and your agronomist to figure out what to do in 2022. In some cases, that may include growing the same crop as last year. Normally there is the concern of disease buildup, but in areas with insufficient moisture for herbicide breakdown, the disease may not have been very high in 2021, so there may not be much inoculum to carry over to the subsequent crop. This is not ideal, but growing the same crop might help get out of the problem of what to do with herbicide carryover this coming year.

Producers also need to know not only the brand names of herbicides but also the active ingredients in the herbicides they are applying. If they didn’t get a letter in the mail warning of the risk of herbicide carryover from a manufacturer, producers are not necessarily safe. They may have used a generic version of a herbicide, and the generic company may not have the resources to support the product and contact producers.

For example, there are 410 herbicide brands in the Manitoba and Saskatchewan Guides to Crop Protection, but only 74 active ingredients. About 35 to 40 are the most commonly used, and about 20 are residual. If you know your active ingredients and know the risk, then it can be avoided going forward.

There aren’t any testing processes being provided by labs to be able to diagnose these issues, so that’s why producers need to be very conservative going into 2022.

Watch the presentation here:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=iwKpvtiooR0