Features

Weed Management

Assessing the risk of herbicide carryover

In-season rainfall after application is the most important factor.

March 23, 2022 By Bruce Barker

Group 14 sulfentrazone damage on lentil.

PhotoS COURTESY OF Clark Brenzil

Group 14 sulfentrazone damage on lentil.

PhotoS COURTESY OF Clark Brenzil Like rubbing salt into a wound, the effect of the 2021 drought lingers on with the potential carryover of herbicide residues that can harm rotational crops in 2022. The biggest factor in assessing the risk of herbicide carryover is 2021 in-season rainfall, which was very limited in many areas of the Prairies.

“Assessing herbicide carryover is complex and it isn’t an easy thing to nail down with great confidence,” says Clark Brenzil, provincial specialist, weed control with the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture in Regina. “It is more of a risk assessment and where you sit on the risk aversion curve.”

There are many factors that affect herbicide carryover from soil residual herbicides. Rotational crop sensitivity, soil pH, herbicide breakdown rate, soil buffering depending on organic matter content and clay content, and weather. Under “normal” conditions, herbicide manufacturers take these factors into consideration and provide rotational cautions on the label to guide agronomists and farmers. But under abnormal conditions, such as the 2021 drought and in some circumstances 2020 drought, the label is less useful in guiding rotations.

“The best we can do is an educated guess,” Brenzil says.

Factors affecting carryover

While there are several mechanisms that degrade herbicides in the soil, the two major ones are chemical hydrolysis and microbial activity. Both of these are heavily influenced by in-season soil moisture. Other factors like organic matter and soil clay content determine the amount of free residue that is available for microbial use. Higher contents will result in more herbicide being affixed to the organic matter or clay, which can inhibit the decay process. On the other hand, high levels can also protect sensitive plants from sudden release of herbicides after a rain. The interactions are complex, indeed.

Photo degradation occurs when the herbicide is exposed to sunlight. This occurs with Group 3 herbicides trifluralin and ethalfluralin when left on the soil surface. The gassing off of herbicides when exposed to the atmosphere, volatilization, can occur with Group 3 herbicides and thiocarbamate Group 15 triallate and EPTC (formally Group 8). However, these are relatively minor mechanisms.

Chemical hydrolysis as a mechanism is largely limited to Group 2 sulfonylurea (SU) herbicides and Group 5 triazine herbicides. In this process, water cleaves the herbicide molecule in half to render it harmless to rotational crops.

Microbial activity is responsible for herbicide degradation in most herbicide groups. The soil microbes use the herbicide residues as food, chewing through the residues to break them down into components that will not harm rotations crops. Soil microbes are most active in soils with 50 to 100 per cent field capacity, so in-season rainfall is a driving factor in herbicide degradation.

Temperature has an indirect but major influence on herbicide degradation for both chemical hydrolysis and microbial degradation. Soil microbes are most active between 10 C and 30 C. On either side of those temperatures, microbial activity and herbicide degradation slows. Microbial activity stops below 5 C, but hydrolysis can still take place although at a slower pace until freeze-up.

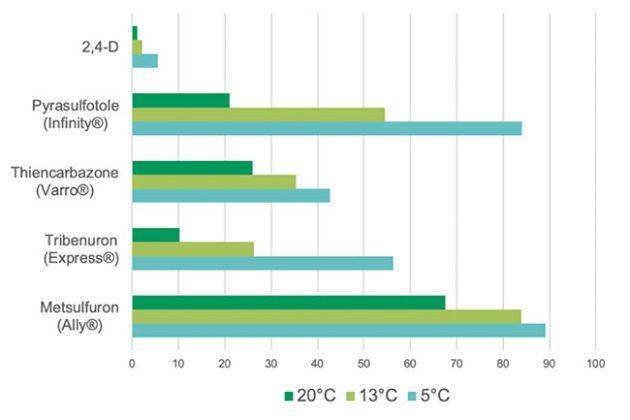

Research led by retired Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research scientist Allan Cessna and Diane Knight at the University of Saskatchewan looked at the effect of temperature on herbicide breakdown in biobeds, but helps to shed light on how temperature influences degradation in the soil. In the research, the one-half life of Group 4 herbicide 2,4-D was relatively unaffected by differences in temperatures of 5 C, 13 C and 20 C, although 2,4-D has a relatively short one-half life in the first place. Conversely, Group 27 herbicide pyrasulfotole was largely influenced by temperature.

The risk of herbicide carryover affecting crops in 2022 is high in many areas of the Prairies. Shown here is Group 27 pyrasulfotole damage to faba bean.

PHOTO Courtesy of Eric Johnson.

Assessing the risk

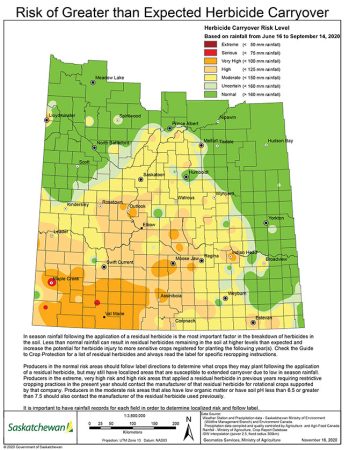

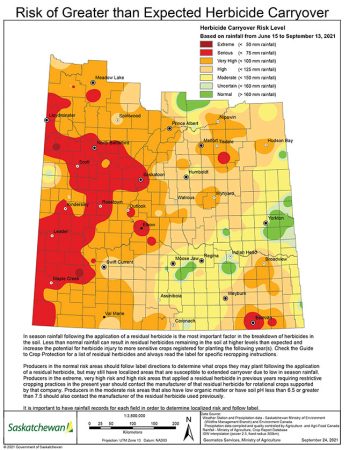

With no lack of hot temperatures over the last few years, in-season rainfall becomes the most important factor to consider for the risk of herbicide carryover. Brenzil leads an initiative at the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture to map out the herbicide carryover risk. The risks areas are based on in-season rainfall, either early June to early September, or mid-June to mid-September. These two time frames provide scenarios for early or later herbicide applications.

The Saskatchewan Guide to Crop Protection has a list of herbicides that have residual activity, and their re-cropping restrictions. These are the herbicides most at risk of carrying over and causing crop damage under low moisture conditions.

“Over the last five years, we haven’t had the best conditions for herbicide breakdown,” Brenzil says. Normal risk that herbicide labels are based on is in areas that received more than 6.25 inches (160 mm) of rainfall in the growing season. The risk increases as in-season rainfall declines. “Generally, greater than six inches of rainfall is need through June, July and August to promote herbicide breakdown,” Brenzil says. “Once you get below four inches, most herbicides will be affected by reduced herbicide degradation.”

Brenzil also cautions that rainfall is required throughout the growing season. He says that in the 2021 maps, even those areas that are listed as ‘normal’ could be at risk as they received most of the rainfall in early June and mid-August, resulting in little time for microbial activity.

Herbicide stacking over two years is a concern

Lack of rainfall in 2020 and 2021 in some areas is like a “piling on” penalty in football. In these areas, the risk of herbicide carryover is even greater because the potential exists for herbicides applied in 2020 to still be present in soils as well, because conditions for breakdown were poor in both years.

Brenzil uses the example of Group 14 Authority (sulfentrazone) herbicide. While crops like canola, wheat, and barley can be grown the year after application (one winter), lentil can be sown two years after application (two winters). However, if rainfall was not adequate during the year of application, or the previous year combined, there is increased risk of herbicide carryover persisting for multiple years.

“If there were two years back to back with less than three inches of rain each growing season, there is a very high risk of multi-year carryover,” Brenzil explains.

In these cases, snowfall recharge may help very slightly, but with drought conditions drying out the top few inches of topsoil where the majority of the microbial breakdown occurs, this moisture can’t necessarily be counted on to help degradation. The cautious advice is to add one year to the follow crop recommendation for every year with inadequate rainfall.

Manufactures highlight the seriousness of the risk

In connection with the unexpected and prolonged sequence of extreme environmental conditions in 2021, and with the potential for similarly unprecedented weather patterns in the future, BASF has decided to amend certain product labels:

“BASF has submitted, and the PMRA has approved, amendments to the Odyssey brand labels to reflect potential risk of injury to certain sensitive rotational crops. Specifically, durum wheat and canary seed have been moved from a one-year rotational interval to a two-year interval. Additional notes were also added to the label, recommending producers extend the rotational intervals of tame oats, mustard, and non-Clearfield canola by an additional year if drought conditions are experienced following herbicide application, extending oats to a two-year interval and non-Clearfield canola to a three-year rotational interval.

The labels of all BASF’s imazamox based products (Viper ADV, Solo brands, Altitude brands) were also submitted to the PMRA for amendment. In particular, BASF is requesting label amendments to reflect the potential risk of injury to certain sensitive rotational crops and the conditions under which these risks are most prevalent (subject to PMRA approval). PMRA approval was pending at press deadline.”

Saskatchewan Pulse Growers has also published a fact sheet “Herbicide carryover risks and considerations”, which highlights herbicides at risk of carryover and contains guidance by BASF, Adama and Corteva.

Testing for carryover is inconclusive

Several different ways of testing or predicting the risk of herbicide carryover have been investigated over the years. Many herbicide labels recommend that a field bioassay be conducted prior to planting a sensitive rotational crop. Brenzil says that the disadvantage is that the results don’t tell what can be planted in the current cropping year, and that the selection of where the field bioassay must be representative of the entire field. Plus, an original check strip should have been set up to compare to the field bioassay.

Chemical analysis for herbicide residues is possible, but costs $300 per sample. The analysis can tell what absolute ppm is present in the soil, but it doesn’t indicate if that level would impact sensitive crops, because the influence of binding to clay and organic matter is not taken into account.

Lab bioassays have been developed, where a soil sample is sent to a lab and sensitive crops grown in the soil. Results can be obtained in three to six weeks, but no lab is currently offering the service. Brenzil says this service requires a large investment in infrastructure of greenhouses and technicians, but is required only occasionally.

In the end, the risk of unexpected herbicide carryover is high in many areas of Saskatchewan. While Alberta and Manitoba don’t have formalized risk maps, growers, even in Saskatchewan, should use their own weather records to help assess their risk as precipitation can be very localized. They can also talk to their agronomist and herbicide representative to obtain additional opinions.

“Follow crop choices after residual products should be very conservative again in 2022, and select the safest crop to avoid injury,” Brenzil says. “Remember, everyone gets all bent out of shape about the Group 2 herbicides but there are others in Groups 4, 14, 27 and recently Group 13 that also have issues with dry conditions.”