Features

Agronomy

Cereals

Does intensive wheat management pay?

Research found that the returns aren’t always there.

April 11, 2022 By Bruce Barker

Intensive management of wheat doesn’t always pay.

Photo by Bruce Barker.

Intensive management of wheat doesn’t always pay.

Photo by Bruce Barker. Pouring on the groceries to spring wheat is tempting in highly productive areas of the Prairies. Pushing yields up to 100 bushels per acre is pretty satisfying. But does it pay? Research across the Prairies looked at maximizing yield and what that did to net returns.

“Newly registered Canadian Western Red Spring (CWRS) wheat cultivars are increasingly high yielding. Because of that, we need to consider genetics and management when setting yield targets,” says Anne Kirk, cereal crop specialist with Manitoba Agriculture in Carman.

Research has shown that between the 1950s and the early 1990s, the rate of yield gain in CWRS wheat was about 0.35 per cent increase per year. From the early 1990s to 2013, that rate of gain had increased to 0.67 per cent per year. The increase was attributed to a combination of better genetics and more intensive management.

Kirk has reviewed research looking into management practices for high yielding CWRS wheat. One of the first parameters looked at was seeding rate. Currently in Manitoba, the recommended target plant stand is 23 to 28 plants per square foot. She say that can vary depending on environment. Research by North Dakota State University found that across all environments, the optimum seeding rate was 32 seeds/ft2, but was 38 seeds in low yielding environments and 31 seeds in high yielding environments.

A Manitoba study looked at target plant density and the impact on yield in 2017 and 2018 at Carberry and Melita. A range of seeding rates were applied to target plant stands from

15 plants/ft2, up to 39 plants/ft2. In three out of four site years, there was no significant difference in yield between seeding rates. At the fourth site, 15 plants/ft2 yielded significantly lower, with the remaining four higher seeding rates of 21, 27, 33, and 39 plants/ft2 yielding the same.

“What we determined is that we didn’t have to adjust our recommended target plant stand from the current 23 to 28 seeds/ft2. However, there may be other reasons why farmers want to increase plant stand including increased competition against weeds, and fewer tillers for ease of fungicide timing,” Kirk says.

Research by Amy Mangin and Don Flaten of the University of Manitoba looked at the optimum rate, source and timing of nitrogen (N) for high yielding spring wheat in Manitoba in 2016 and 2017. At seven site-years in Manitoba, the economic optimum range of soil test plus fertilizer N was 1.9 to 2.9 pounds of N per bushel, with an average of 2.3 lbs. N/bu to grow an average of 86 bu/acre wheat yield. The former recommendation was 2.5 to 3 lbs. N/bu. This shows better N use efficiency, but the higher yield potential also means the overall N requirements per acre are much larger with high yielding wheat varieties.

Split rate applications were also investigated in their study. Split rates of 80 pounds N at planting plus 30 or 60 pounds at stem elongation or flag leaf were compared to equivalent rates of 110 or 140 pounds applied entirely at planting. At the Gold-level sites under a moister growing environment, there was a 3.3 bu/ac yield advantage with a split application at the stem elongation stage. Whether that pays for the additional cost of the split application would depend on individual circumstances, but it shows that a split application could be used as a risk management tool. Later application at the flag leaf stage would contribute to higher protein.

“For split application, the nitrogen should be available by the time of maximum crop uptake, which is at the stem elongation stage,” Kirk says.

In a Manitoba Agriculture study that ran from 2018 and 2020 at Arborg, Carberry, Melita and Roblin, four CWRS wheat varieties, AAC Brandon, AAC Cameron VB, AAC Viewfield and Cardale, were compared in a standard and advanced input environment. The standard input included 100 lbs. N/ac with no PGR and no fungicide. Other treatments included an additional 50 lbs. N, a PGR applied at BBCH 31-32, fungicides at flag leaf and anthesis. And an Advanced treatment with all the additional groceries of additional N, PGR, and two fungicides was also compared.

Generally, at all sites, the PGR application reduced height by zero to three inches (zero to eight cm). Crop height without PGR ranged from 26 inches (65 cm) to 31 inches (80 cm). Some differences in yield were observed. In 2018, the additional 50 lbs. N/ac produced a significantly higher yield at two of four sites with an increase of six to eight bu/ac. In 2020, the highest yield at two of three sites was with the advanced treatment with about seven bu/ac higher yield.

“In both years, the conditions were fairly dry. There was little disease so we didn’t see any benefit to the fungicide applications, and there wasn’t any lodging, so the benefit of a PGR wasn’t realized,” Kirk says.

The additional 50 lbs. N/ac resulted in an increase in grain protein of between 0.2 per cent and 2.2 per cent.

“We would have seen greater results from the additional fungicides and PGRs if there would have been better growing conditions,” Kirk says.

Saskatchewan research looked at differences in wheat classes

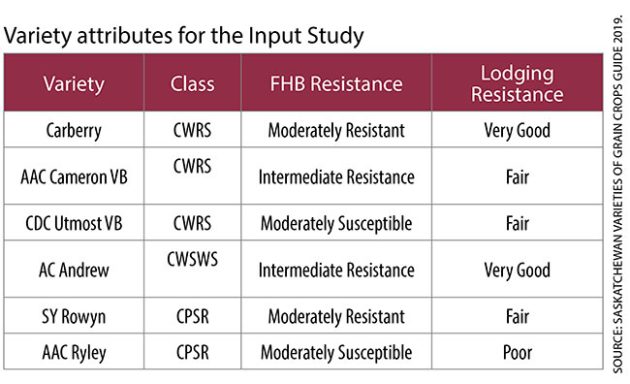

Research led by Jessica (Pratchler) Slowski, formerly with the Northeast Agriculture Research Foundation and now with Clearview Agro at Foam Lake, Sask., was conducted at five Agri-Arm sites looking at intensive wheat management. Small plot research was conducted at Indian Head, Melfort, Scott, Swift Current, and Yorkton from 2017 to 2019. Six wheat varieties from three market classes were selected based on genetic differences in Fusarium Head Blight resistance, lodging resistance, maturity, yield, and protein content. Each variety was grown under three progressively intensified management levels.

Variety attributes for the Input Study

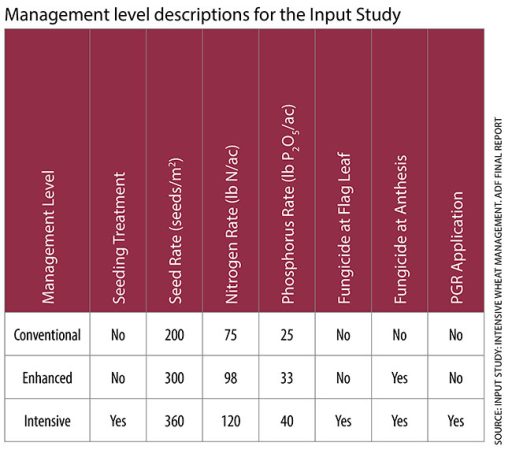

Three management levels were imposed on the different wheat varieties. Conventional, Enhanced and Intensive levels were compared at each site.

Three management levels were imposed on the different wheat varieties. Conventional, Enhanced and Intensive levels were compared at each site.

Management level descriptions for the Input Study

Slowski reports the CWRS varieties tended to respond the most to Intensive management, mainly because of a better response to seed treatment compared to CPSR or CSWSW varieties. Intensive management produced maximum yield for CWRS and CPSR varieties. The CWSWS variety was less responsive to Intensive management level.

Slowski reports the CWRS varieties tended to respond the most to Intensive management, mainly because of a better response to seed treatment compared to CPSR or CSWSW varieties. Intensive management produced maximum yield for CWRS and CPSR varieties. The CWSWS variety was less responsive to Intensive management level.

Enhanced management often led to hastened maturity across all varieties, but varietal selection for early maturity was also important to prevent delayed maturity with Conventional and Intensive management.

Test weight and seed size differences were largely attributed to genetic differences and any responses to management were of little practical agronomic importance, Slowski says.

Fusarium Damaged Kernels (FDK) values showed increased control with Enhanced management, but differences were largely because of genetics.

An economic analysis, using commodity prices and input costs at the time, was also conducted comparing varieties, sites and management level. Averaged across the three-year study period, total returns above expenses were variable across treatments, ranging from losses of $66 per acre to profits of $91/ac.

Averaged across all site years and varieties, the Conventional management level had a three year average net return of $63.79/ac, compared to $31.03/ac for the Enhanced level and a loss of $12.80/ac with the Intensive level.

Overall, Conventional management consistently provided the best net returns per acre across varieties and market classes. However, these economic returns can change depending on commodity prices and input costs. Each individual farming operation has its own cost base, yield and commodity price. As a result, these returns will vary from farm to farm.

“The results of this experiment indicate that Conventional management of wheat in Saskatchewan continues to provide the best return on investment. Although under some circumstances, Enhanced management can be beneficial and profitable,” Slowski says.