Features

Cereals

Agronomy

Diseases

Tracking barley yield robbers

On the lookout for changes in existing disease problems and emergence of new diseases.

April 4, 2020 By Carolyn King

Ramularia leaf spot has been spreading rapidly to many countries, including Ireland, where this photo was taken. The project team is checking to see if the disease has arrived in Western Canada.

Photo courtesy of Kelly Turkington.

Ramularia leaf spot has been spreading rapidly to many countries, including Ireland, where this photo was taken. The project team is checking to see if the disease has arrived in Western Canada.

Photo courtesy of Kelly Turkington.

Staying on top of barley disease issues is critical for barley growers, pathologists, breeders and agronomists. “We need to identify emerging and changing disease issues so that we can put in place strategies to mitigate those issues. If we don’t, we could have a potential wreck on our hands, especially if we let the problem get well established rather than managing it at an earlier stage,” says Kelly Turkington, a plant pathologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lacombe, Alta.

Turkington is leading a Prairie-wide, multi-agency project to provide up-to-date information on barley pathogens. The project involves: surveying barley fields to determine pathogen distribution and prevalence; testing pathogen strains to look for shifts in virulence and other key properties; and tracking emerging concerns like Ramularia leaf spot.

The project runs from 2018 to 2023. Research personnel with AAFC, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry (AAF), the University of Saskatchewan, the University of Alberta and the Canadian Grain Commission are collaborating on the project. It is funded under the Canadian Agricultural Partnership’s Barley Cluster, a joint initiative between AAFC and the Barley Council of Canada. Industry funding is from Alberta Barley, SaskBarley, the Manitoba Wheat and Barley Growers Association, and the Brewing and Malting Barley Research Institute.

Shifting pathogens

“Like any biological entity, barley pathogens will adapt to their environment,” Turkington says. “So the disease spectrum could change quite dramatically depending on the barley varieties that are grown, the cropping practices that are used, and any shifts in the climate that might occur.”

For example, repeatedly growing barley varieties with the same source of genetic resistance, especially in very short rotations, will select for pathogen strains that can infect those varieties. And repeatedly using fungicides with the same mode of action will select for strains that are less sensitive or resistant to that fungicide class. So, once-reliable disease management tools will no longer provide the protection that growers expect.

Turkington has been involved in monitoring barley pathogens since the mid-1990s. “Probably our first experience with quite dramatic shifts in virulence in terms of host resistance occurred with the scald pathogen in the mid-to-late 1990s,” he notes.

“At the time, some barley varieties had excellent resistance to scald, an important leaf disease. However, this was largely based on major single-gene resistance [and pathogens can more easily overcome single-gene resistance than resistance based on multiple genes]. When those varieties were grown continuously, the scald pathogen adapted to the resistance source and the varieties’ reaction to scald changed within two to three years from being highly resistant to being intermediate or, in some cases, quite susceptible.”

In the 2010s, Turkington and his University of Alberta colleagues Stephen Strelkov and Alireza Akhavan saw similar shifts with net blotch, another leaf disease. Likely, continuously growing the same resistant variety or using short rotations resulted in a shift in the pathogen’s virulence.

As well, Akhavan and colleagues found that the net blotch pathogen was becoming less sensitive to propiconazole, an older triazole fungicide, and to pyraclostrobin (Headline), a strobilurin fungicide.

“Propiconazole was a common fungicide and tended to be a little cheaper, so maybe it was used more frequently and especially in short-rotation barley production. And often it was applied at a herbicide timing, and sometimes at a half rate. Invariably that did not provide sufficient control of net blotch. So, the farmer would need to go back in with another application at flag leaf emergence or head emergence,” Turkington explains.

“The strobilurins tend to be at very high risk of fungicide resistance development. So, you’ll often see a wholesale shift from the pathogen being fully sensitive to being fully insensitive or resistant to that particular active. We’re not seeing that type of dramatic shift with the net blotch pathogen, but we’re seeing indications that we need to be cautious [with applying these products].”

Focusing on leaf pathogens

The current project’s primary objective is to assess the prevalence and spectrum of barley diseases that are present in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

For this work, the project team is collecting diseased leaf samples from about 30 to 50 barley fields per province per year. The survey mainly targets commercial barley fields. In addition, Kequan Xi and Krishan Kumar with AAF in Lacombe are monitoring the disease nurseries that AAF’s Field Crop Development Centre uses for evaluating disease response in barley breeding materials.

The project team analyzes the leaf samples in the lab to identify the pathogens, and also conducts detailed testing on some key leaf pathogens. In particular, as part of a PhD project at the University of Alberta, graduate student Dilini Adihetty is evaluating the spot blotch pathogen for variation in virulence, variation in genetic characteristics at a molecular level, and in fungicide sensitivity. And the project team is assessing the scald pathogen and the net blotch pathogen for changes in virulence on different barley varieties.

Why focus on leaf pathogens? “Traditionally the biggest barley disease issues in terms of yield loss and impacts would be the leaf diseases,” Turkington explains. These diseases can cause yield losses of more than 30 per cent in susceptible barley varieties when conditions favour disease development.

The three major leaf diseases in Western Canadian barley are scald (caused by Rhynchosporium secalis), net blotch (Pyrenophora teres) and spot blotch (Cochliobolus sativus).

“Scald tends to be an issue in cooler, wetter regions. So traditionally we find it in central and northern Alberta up into the Peace Region, and occasionally in northwestern Saskatchewan,” he says.

Net blotch has a net form and a spot form. “As the name implies, the net-form net blotch lesions can have a netted appearance, whereas the spot form tends to produce oval or elliptical brownish lesions.”

During the past few decades, these two forms have switched back and forth in terms of their relative predominance. The net-form is more common at present. “There seems to be a background level of intermediate to maybe higher levels of resistance to spot-form net blotch [in our current barley varieties],” Turkington notes.

“Spot blotch has traditionally been more of an issue in the central to eastern Prairies. But over the last 10 years or so, we have started to detect it at increasing levels in our central Alberta surveys.”

The spot blotch fungus can infect more than just the leaves. “The fungus can move quite readily from the leaf tissue to the developing barley kernels where it causes kernel smudge. Kernel smudge may have implications for acceptability for malt status or downgrading due to grain discoloration,” Turkington explains. “Also, if you plant that infected seed, the pathogen can be quite aggressive on seed germination, seedling growth and stand establishment. Plus this fungus is a cause of common root rot.”

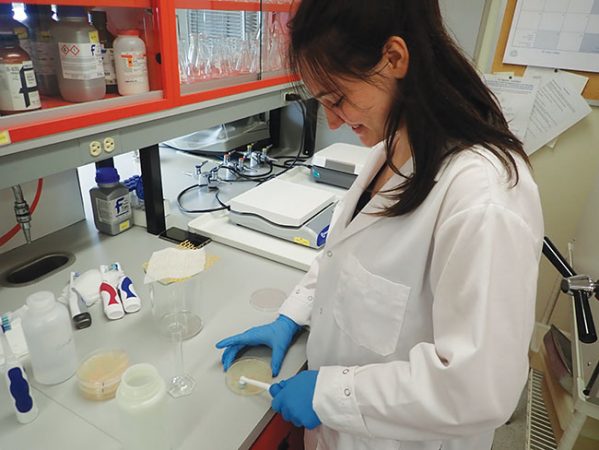

Summer student Marieke De Vynck harvests scald spores from agar plates for inoculation of barley germplasm to test for variations in the pathogen.

Photo courtesy of AAFC Lacombe, Plant Pathology Laboratory.

Checking stripe rust’s status

The project team is also taking a close look at stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis) in barley, which is a potentially emerging issue in the western Prairies.

“In some other major barley-producing areas, stripe rust in barley can be a devastating disease, causing major yield losses in susceptible varieties and where the disease is not adequately controlled with fungicides,” Turkington explains.

There are signs that the disease could become an issue in Alberta. “Over the years, Kequan and Krishan have documented quite significant levels of stripe rust primarily in their disease nurseries and very occasionally in commercial barley fields. Also, they sometimes see pathotypes of the stripe rust pathogen that have dual virulence on wheat and barley. These dual types tend not to be as common as the barley type, which is more adapted to barley, and the wheat type, which is more adapted to wheat.”

Stripe rust requires a living host to survive, so it doesn’t usually overwinter on the Prairies. Typically, the pathogen’s spores are carried by the wind from the U.S. into Canada. “For Alberta, most of the stripe rust inoculum comes from the Pacific Northwest – Washington State, Oregon and northwestern Idaho. If you think about stripe rust moving into the Lethbridge area, a parcel of air going over eastern Washington State can reach Lethbridge in less than half a day,” he says.

“The central to eastern Prairies can find stripe rust in wheat, but not so much in barley. Most of their inoculum comes from Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska.”

Turkington thinks that a key reason why barley stripe rust is not a serious issue at present in Western Canada is that winter barley is not grown on the Prairies and very little winter barley is grown in the stripe rust source regions in the U.S. However, that could change if, for example, breeding advances result in winter barley varieties that are able to survive the harsh Prairie winters.

According to Turkington, good sources of stripe rust resistance are available in the barley germplasm and in some of the current barley varieties. So, if monitoring efforts show that barley stripe rust is starting to become a concern, then growers and breeders have some options.

Watching for Ramularia leaf spot

The team is also determining the prevalence and distribution of a new disease: Ramularia leaf spot (Ramularia collo-cygni).

“Ramularia has become a global issue in barley. It is highly seed-borne and seed-transmitted [and current seed treatments don’t control it]. Since the early to mid 2000s, it has spread quite rapidly to many regions, including major barley-growing areas in Europe, South America and now Australia,” says Turkington.

This leaf disease can have serious impacts on grain quality and yield. He notes, “A real concern is that, in other growing areas, such as Europe, the pathogen has developed resistance to some of the main fungicide classes. So we’re concerned that the disease could become an issue here.”

Ramularia may already be in Western Canada. He explains, “Over the years, we have seen symptoms that appear to be characteristic of Ramularia, but it is a difficult pathogen to isolate in the lab using traditional agar plating. So Xiben Wang at AAFC-Morden and Sean Walkowiak with the Canadian Grain Commission are using molecular detection techniques to confirm the presence of this pathogen.”

In 2018, the survey detected a few potential occurrences of Ramularia infections, and Wang and Walkowiak are now checking those isolates as well as processing plant samples from 2019.

Disease monitoring at the farm level

This monitoring initiative is providing crucial information that will help plant pathologists, barley breeders and others in developing effective disease management strategies for growers.

But Turkington emphasizes that disease-monitoring is just as vital at the farm level.

“Growers and their crop consultants need to stay on top of the disease situation in their barley fields so they can proactively tweak their management programs. They might change the barley varieties they grow [or rotate the fungicides they apply]. They might consider lengthening the rotational interval between barley crops to at least two years if not longer – these leaf pathogens often need at least two years for decomposition of infected residues so those residues no longer represent a source of inoculum. And if growers see anything unusual or they are concerned about something, they can contact a pathologist working on barley leaf diseases.”