Features

Agronomy

Corn

Barley 180 project seeks to increase yields

Back in the 1990s, Westco Fertilizers tested various practices aimed at achieving 200 bushel/acre barley yields. In small plot trials in central Alberta, the company got a top yield of 190 bu/ac. That’s pretty impressive, but are such yields practical and profitable on a field-scale level in Alberta?

A team of agronomists and co-operators is hoping to answer that question through Barley 180.

This project involves side-by-side field-scale trials at various Alberta locations. One part of each trial has the good management practices already being used by the co-operator. The other part has additional practices, including some that are not commonly used in dryland barley production on the Prairies, such as plant growth regulators. Yield maps and geo-referenced locations for the different treatments are providing an easy way to collect data.

Barley 180 started as a pilot in 2011 with agronomists Steve Larocque of Beyond Agronomy and Craig Shand of Farmers Edge. In 2012, Mike Hilhorst, another Farmers Edge agronomist, joined in. Dr. Ty Faechner, executive director of the Agricultural Research and Extension Council of Alberta (ARECA), is co-ordinating the project and pulling together all the results from the individual trials. Barley 180 is funded by the Alberta Crop Industry Development Fund (ACIDF) and the Alberta Barley Commission.

“We call it Barley 180 because ideally we’d like to hit 180 bushels/acre on a field-scale level, but some areas are just too dry to get to 180 bushels,” says Larocque. “So we’re focusing on how many bushels of barley we can produce for every inch of moisture we get. So maybe it’s ‘Barley 120’ if your area’s average yield is 65 bushels.”

It’s great to aim for that 180-bushel goal, “but the learnings about practices and management are what’s really key, so producers will be able to use the information to achieve a higher yield and be more profitable with it,” adds Faechner.

2011 trials

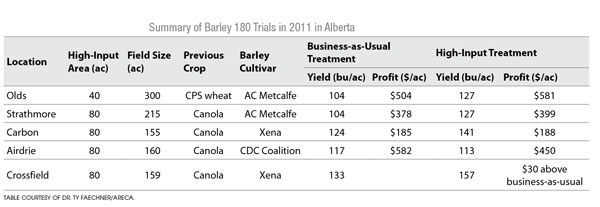

In 2011, Larocque had four sites and Shand had one (see table). Working with their co-operators, they tried various extra practices because they weren’t sure which ones might be most beneficial.

“Ultimately we want to find out which inputs offer the best rate of return,” notes Larocque. “But first we’re focusing on which inputs give the biggest yield increase, and then determining whether we need to focus on a whole package of inputs or perhaps just a couple of them. We do an economic analysis each year, but at the end of the project we’ll determine which ones provide the most consistent returns.”

Shand’s site, a quarter section near Crossfield in the Black soil zone, offers an example of what was done in 2011. An 80-acre portion of the quarter had higher-input treatments, but even the portion with the co-operator’s business-as-usual practices involved a substantial amount of management.

As a base treatment on the entire quarter, they applied 70 lb of nitrogen/ac as anhydrous ammonia in fall 2010. In spring 2011, they applied glyphosate at 1 L/ac plus Express Pro as a preseed burnoff for early weed removal of such volunteers as canola. Based on germination, vigour and 1000-kernel weight tests of the co-operator’s Xena feed barley, they used a seeding rate of 146 lb/ac for a target stand density of 25 plants/ft.2. The seed was treated with Raxil WW. Based on soil testing, they applied a drill blend of 8-40-10-0 with the seed. Assert FL and then Axial were applied for in-crop weed control. The soil test results showed a copper deficiency so foliar copper was mixed with the Axial. They applied pre-harvest glyphosate (1 L/ac) for harvest management and touch-up quackgrass control.

On the 80-acre portion, they increased the seeding rate to 163 lb/ac for a target density of 28 plants/ft.2. At late tillering, they applied top-dress liquid urea ammonium nitrate (UAN) using a sprayer equipped with stream bar nozzles. They used variable rates ranging from 0 to 45 lb/ac of nitrogen. The fungicide Stratego was applied at the flag leaf stage.

On 33 acres within the 80-acre portion, they applied Ethrel, a plant growth regulator (PGR), at about three-quarters of the label rate, just prior to 10 percent awn emergence.

The purpose of the PGR is to shorten and stiffen the straw, so the crop won’t lodge under high nitrogen conditions. “Ethrel has a very narrow window of application, and if you don’t apply it at the right crop growth stage, it could cause serious yield loss. However, if staged properly, it’s reasonably economical at about $11/ac at the three-quarter rate,” says Shand.

Top-dressed nitrogen is intended to boost yields, although opinions vary about the value of the practice. It can sometimes increase protein content in the grain, which could be a problem for malt barley. “Top-dressed nitrogen is a bit of a challenge if you want to do it on a significant amount of acres, particularly if you get some bad weather and time gets tight,” notes Shand. “When we’re top-dressing at tillering, guys also want to spray their canola, barley and wheat for weed control in that same window. However, it is ideal to top-dress UAN with stream bar nozzles in or just before a rain, which is obviously not recommended for most pesticide applications.”

The Crossfield site received 11.8 inches of rain from May 15 to Sept. 15, which is normal for the area. The business-as-usual portion turned out well: it yielded 133 bu/ac and had 10.7 percent protein. The high-input portion without the PGR yielded 146 bu/ac and had 11.7 percent protein. And the high-input portion with the PGR yielded 157 bu/ac and had 11 percent protein.

“On the high-input side where we didn’t use the PGR, we spent about an additional $58 in incremental costs and got an increased revenue of about $53, so we lost about $5. However where we applied both PGR and top-dress nitrogen, we actually made about $30/acre,” says Shand. “To me that was the eye opener: that neither of the extra inputs by itself was necessarily making money, but when we put both together we came out ahead.”

The co-operator also found that, even though the PGR-treated portion had much higher yields, it harvested about 1.5 miles/hour faster than the high-input without PGR portion because of the shorter straw.

According to Shand, he and his co-operator were fairly skeptical at the start of the trial, “but achieving 157 bu/ac was a game changer for us. It really shifted our paradigm as to what is possible when you get the right conditions.”

At Larocque’s sites he and his co-operators tested a variety of extra inputs, for example, PGR applications, fungicide treatments and various nutrient treatments, split nitrogen applications, extra nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, sulphur and micronutrient applications. The greatest yield benefits were from PGRs (about 10 bu/ac extra) and fungicides (about 7 to 10 bu/ac extra).

2012 trials

Based on the promising results from 2011, the project team continued Barley 180 in 2012. (They also started a similar project with wheat, which ACIDF is also funding.)

The 2012 trials were expanded to include eight co-operators and nine sites, with locations in the Dark Brown, Black and Thin Black soil zones. Larocque had two feed barley and two malt sites, Shand had two feed sites, and Hilhorst had three feed sites. At each site, the agronomist and co-operator focused on just one or two extra inputs to keep things simple.

At each of Hilhorst’s sites, the entire field was fertilized at seeding with the producer’s air drill, using variable rate technology with rates based on the soil tests. Then on the high-input portion, they applied Ethrel and top-dressed with liquid nitrogen (28-0-0) at about the five- to six-leaf stage, after the herbicide application. Hilhorst notes, “We top-dressed with almost an extra 100 lb/ac of actual N. Some fields were close to 200 lb of actual N on the treated areas.”

At Shand’s two sites, the co-operators followed practices similar to those used at the Crossfield site in 2011, except in 2012 they applied the fungicide on the entire field and applied the PGR on part of the business-as-usual side, as well as on part of the high-input side. “I felt we were on the right track in 2011,” says Shand. “This year, I wanted to get a better handle on the response to the top-dress nitrogen and the plant growth regulator, to see if last year’s results were repeatable.”

The high-input treatments can have remarkable effects. Faechner describes one near Crossfield: “I’ve never seen a crop that thick; it was actually difficult to walk through it because it was so thick. And there were literally no weeds in it. On the portion where they hadn’t applied the plant growth regulator, the crop was completely lodged, and the part with the growth regulator was standing straight as an arrow. It was amazing.”

Larocque and his co-operators evaluated various high-input strategies for multiple fungicides, extra nutrients, and PGRs in 2012. For example, at one of the malt barley sites, they seeded AC Metcalfe treated with Raxil WW at 160 lb/ac (30 plants/ft.2). In one pass at seeding, they applied 100 lb of nitrogen as anhydrous ammonia in a sideband, plus 70 lb as ESN (controlled release, polymer-coated urea) in the seed row. Then at post-emergent herbicide timing, they applied foliar copper (5% at 0.5 L/ac), foliar zinc (9% at 0.5 L/ac) and a tank mix of the herbicides Axial and Prestige and the fungicide Tilt. At the beginning of stem elongation, they applied the PGR Cycocel Extra at 10 gal/ac; application was a little late because they received the product at the last minute. Then at the late flag leaf stage, they applied the fungicide Twinline.

The purpose of using ESN was to delay the release of some of the nitrogen, so there would be less vegetative growth early on and more nitrogen available later to encourage higher yields. Larocque wanted to try Cycocel Extra because it has more flexibility in timing: it can be applied between late tillering and stem elongation, whereas Ethrel’s application window can be as short as one or two days in some years.

The Barley 180 team is now in the process of analyzing the 2012 results. Unfortunately, many of the sites encountered weather problems such as hail, dry conditions and high temperatures, so yields were down.

Both Hilhorst and Shand expect the results will show the extra nitrogen treatments on their sites didn’t pay in 2012. “We just didn’t have the rain we needed to crank out the extra bushels we fertilized for,” says Shand.

In contrast, they think the Ethrel treatments might turn out to have been economical. Hilhorst notes, “PGRs can virtually eliminate lodging. As well, in many cases, Ethrel shortened the barley by six to 10 inches, so there’s much less straw to put through the combine, making harvest more efficient – you go through it quicker, it’s easier to thresh, and so on.”

Hilhorst is seeing a lot of interest in the PGR results because it’s a fairly new practice for barley growers. “In our area, there is as much interest in the plant growth regulator as there is in applying tremendous amounts of nitrogen,” he says.

“Not many of these plant growth regulator products are registered in Canada, so we don’t have a lot of access to them, although that may change down the road. Ethrel is pretty reasonable at about $10/ac, or $15/ac if you go to a higher rate, but some other products are over $40/ac. The hope is that some of those products may come off-patent soon and then the price might decrease.”

Larocque has analyzed the results for the malt barley site described above. The yields were relatively low because of low rainfall. The biggest yield benefit came from the PGR. Even though Cycocel Extra’s effectiveness was reduced somewhat due to the late application, it still provided an eight to 12 bu/ac yield increase compared to the untreated check. It reduced lodging but didn’t shorten the straw as much as Ethrel.

Larocque has noticed another advantage of PGRs. “We’re getting a higher yield and a lower protein when we use the plant growth regulators, which is especially important when we’re aiming for malt barley.” However, he cautions, “The risk with PGRs is if there is an adverse weather event or if the crops are under stress, then PGRs can reduce yields by 20 or 30 percent in some cases. I’d need more research before I applied them to my regular agronomy programs.”

The ESN treatment provided a 5 to 6 bu/ac increase, but it boosted the protein by 2.5 percent, making the barley unsuitable for malting at 13 percent protein. “I don’t think ESN is a good strategy because you can’t control the release of the nitrogen,” says Larocque. “If you get a lot of heat and moisture early in the season, the nitrogen is released and you spent money for nothing.

“Overall, the economics of the trial required a 14 bu/ac increase over the check to break even. We got a 13 bu/ac increase,” he adds. “A big part of the cost was Cycocel at $46/ac; if we had used Ethrel, the cost would have been much less. And if we had replaced the ESN with anhydrous, the cost would have been even lower.”

Based on these results and the preliminary results from his other trials, Larocque says the two things that have been the most important so far are the fungicides, such as Prosaro or Quilt, and the plant growth regulators.

Next steps

Once the 2012 results are analyzed, the project team will consider possible plans for 2013. The three agronomists feel there is still more to be learned to really home in on what it takes to maximize barley yields.

“It’s a great opportunity to be part of this leading edge research,” says Hilhorst. “The yield mapping and other precision ag technologies enable us to do on-farm research at a large scale, which I think is much more relevant than anything else.”

According to Shand, the project is beneficial because both the agronomists and co-operators are learning a lot, “plus we are getting to do this without taking on the risk because of the funding.” He notes the challenge for this to become large scale across clients’ entire farms or a portion of their farm is that it’s a very significant amount of risk given the additional dollars of inputs. “So we really have to hammer down which of these best management practices are economical and are going to give us the biggest bang for our buck.”

Larocque adds he’s hoping they’ll be able to provide recommendations depending on a producer’s particular area, and advice on how to scale up the intensive management. “Using growth regulators, multiple fungicides and split applications of nitrogen may be great on 80 acres, but how do you do that on 5000 acres?”

February 28, 2013 By Carolyn King

The high-yield treatment at heading at a site in the Crossfield area in 2012. Side-by-side field-scale trials in Alberta aim for 180 bu/ac barley.

The high-yield treatment at heading at a site in the Crossfield area in 2012. Side-by-side field-scale trials in Alberta aim for 180 bu/ac barley.