Irrigation

Understand crop water use to guide management

It is early July and there are two inches of moisture stored in the

soil. How long will the crop last? That was a frequent question in 2009

for some producers on the Prairies. However, understanding how much

water a crop uses at each crop growth stage can give drought-stricken

farmers a tool for planning management decisions, and maybe even a

little peace of mind.

February 24, 2010 By Bruce Barker

|

|

| How long can this crop last without rainfall? Photo by Bruce Barker.

|

It is early July and there are two inches of moisture stored in the soil. How long will the crop last? That was a frequent question in 2009 for some producers on the Prairies. However, understanding how much water a crop uses at each crop growth stage can give drought-stricken farmers a tool for planning management decisions, and maybe even a little peace of mind.

Comparing the soil moisture available to the crop’s needs can be valuable in making decisions such as whether to invest in costly inputs like foliar fungicides or in marketing decisions, says Alberta Agriculture agronomy research scientist, Dr. Ross McKenzie. And it can also indicate how long a crop might be able to hang on. “Just as you wouldn’t apply high rates of fertilizer if moisture is likely to limit crop growth, maybe applying fungicide is not a good investment if the crop isn’t likely to achieve its full potential,” he says.

Water use is measured as evapotranspiration (ET), evaporation from a wet canopy or bare soil plus transpiration, defined as the water vapour plants lose through stomata, the pores on the undersides of leaves. The stomata open to release moisture, drawing water up from the roots for photosynthesis and other processes in the plant. Transpiration cools the plant, but if conditions are too hot or too dry, the plant closes the stomata to limit moisture loss, then reopens them when conditions improve.

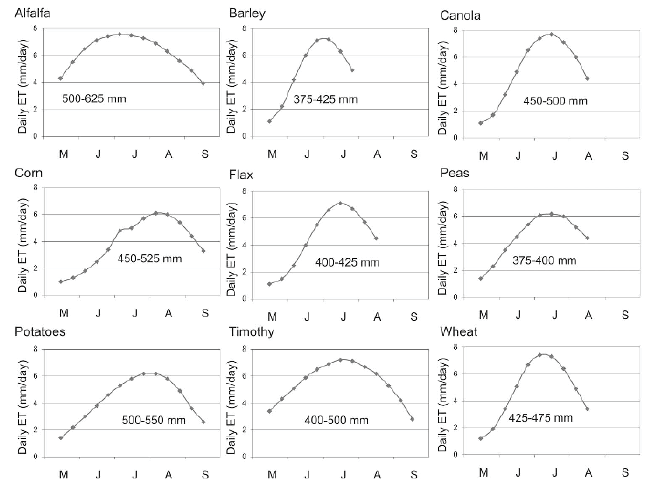

Under optimum moisture conditions, peas use about 375 millimetres (15 inches), barley about 400 to 450 millimetres (16 to 18 inches), potatoes 500 to 550 millimetres (20 to 22 inches) and alfalfa up to 625 millimetres (25 inches) of water per year. With that amount of moisture, water does not limit the productivity of the crop and if nutrients, disease or insects do not limit productivity, harvest can match the crop’s full yield potential.

Very good yields are possible with less moisture than these amounts, but there are critical times when inadequate moisture can stunt cereals. The number of heads a cereal plant can produce is set at tillering. Any stress, such as lack of moisture or nutrients reduces the number of tillers and the number of heads, lowering yield potential. The length of heads, and the potential number of kernels on each head is also set at tillering. Whether all those kernels develop and what size they may be depends on various factors including moisture availability during grain filling.

The yield potential of canola and peas is set during flowering. Under good moisture conditions, canola branches and flowers more extensively, increasing yield potential.

During establishment (one- to four-leaf stage), cereal crops use very little moisture, usually less than two millimetres per day. By mid- to late-June barley uses about six millimetres per day. At the boot and heading stage, moisture use peaks at seven millimetres per day. A wheat crop at heading, or canola in full bloom is at peak water use, taking up more than seven millimetres per day, or almost two inches in a week. Alfalfa uses almost eight millimetres per day at flowering under good moisture conditions, but once it is cut, water use drops down to two millimetres per day and takes about 10 days to get back up to six millimetres.

The other side of the equation is how much stored water is in the soil. Rough estimates have been developed that show how much water is stored in the soil per foot of moist soil, soil that can be rolled into a ball in a person’s hand. Coarse, sandy loam soils hold about 25 millimetres (1 inches) of water per foot of moist soil. Medium, loam and clay loam soils hold 37.5 millimetres (1.5 inches) per foot, and fine, clay soils hold 50 millimetres (2 inches) of water per foot of moist soil.

So, if a grower finds that in early July he has two inches (50 millimetres) of stored soil moisture, and a wheat crop in the boot stage would be using about seven millimetres of moisture a day, the crop could hang on for a about one week before yields would start to decline. Not exactly comforting news, but at least it provides a guideline for management practices.

|

|

| Approximate daily water use and total growing season water use in millimetres (mm) for some commonly grown crops in Alberta. Average water use shown indicates soil moisture as being adequate throughout the growing season. Graphics courtesy of AARD.

|

Manage soil water

To save soil moisture, McKenzie is a great believer in direct seeding and minimizing the use of cultivation. “You lose a half to an inch of water with each tillage pass,” he says. “It takes four or five inches to get wheat, barley or canola through their vegetative growth before any grain is produced. My trials have shown each inch of moisture after five inches will produce five or six bushels of wheat, seven to nine bushels of barley or 3.5 to 4.0 bushels of canola. Conserving soil moisture by direct seeding increases yield potential.”

McKenzie recommends taking soil cores in the spring just before seeding to estimate the amount of stored soil moisture. “Coupling soil moisture with average growing season precipitation helps you estimate crop yield potential,” he says. “Then, you can make final decisions on the amount of fertilizer to apply to meet each field’s yield potential.”

Soil cores also show the impact of the previous crop, which can also be useful in planning rotations. A pea crop, with its lower water use and shallow rooting depth generally leaves moisture below the 60-centimetre (24-inch) depth for a deeper-rooted crop, such as a cereal or canola in the following year. Peas can even replace fallow in rotations for dry areas where continuous cropping increases risk.

Cereals and canola root down a full metre (40 inches), so they can use moisture left deep in the soil profile by shallower rooted crops such as pea. McKenzie looks at hundreds of soil cores every fall and almost always sees roots in the soil to three and four feet depths (roughly one metre to 1.21 metres). If moist soil is left below four feet, sunflower and alfalfa have very deep roots and can scavenge moisture and nutrients leached beyond the reach of other crops.

Roots grow into and proliferate in moist soil, but they can’t grow through dry soil, says McKenzie. “You may find roots in dry soil,” he says. “But that’s because they’ve spread through moist soil and dried it out; they can only grow in moist soil.”