Features

Agronomy

Irrigation

Tips for new growers of irrigated corn

Saskatchewan’s growing conditions aren’t exactly ideal for corn, a crop that loves heat and water. But with the development of shorter-season hybrids, an increasing number of Saskatchewan growers are trying corn for silage, grazing or even grain. Irrigation can play a key part in making corn production more successful.

December 12, 2016 By Carolyn King

Silage corn production is increasing in Saskatchewan Saskatchewan’s growing conditions aren’t exactly ideal for corn

Silage corn production is increasing in Saskatchewan Saskatchewan’s growing conditions aren’t exactly ideal for corn“Irrigation can definitely boost corn yields – whether that’s more tonnes of silage or more grazing days per acre,” says Sarah Sommerfeld, a regional forage specialist with the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture in Outlook, Sask. “But the choice of whether to irrigate would relate back to the producer’s own management and how all the other pieces on the farm fit into production of that corn.”

In particular, irrigation is needed to maximize grain corn yields. “Grain corn uses from 16 to 20 inches of water. Our average [growing season] rainfall won’t cover that, so irrigation is always needed unless you have a year like 2016 when we have more than sufficient water,” notes Joel Peru, a provincial irrigation agrologist with Saskatchewan Agriculture, also based in Outlook.

If you’re growing grain corn under irrigation, Peru recommends ensuring the soil contains at least 60 per cent plant-available water throughout the growing season. “This will allow the corn to have sufficient water to reach its yield potential.”

He says the most critical stages for irrigation of grain corn are during germination and early growth – so the crop gets off to a good start – and during reproductive growth, from tasselling to grain filling. In the reproductive stages, corn can use almost 0.3 inches of water per day.

For irrigating silage and grazing corn, the reproductive growth stages are the most critical time. “The period from flowering right through to cob filling is where you’re going to get your yield, and where you really want to manage and monitor your moisture,” Sommerfeld says.

The recommended timing for irrigation termination is the dent stage for grain corn and grazing corn, and about two to three weeks before silage harvest for silage corn. Sommerfeld adds, “Corn is a long-season crop so make sure you’re not ending irrigation too early. For silage or grazing corn, make sure there is enough moisture to carry the plant through until the harvest end date, whether that’s your silage cutting date, or the first killing frost for grazing.”

More tips

Some of the most common questions that Peru and Sommerfeld get from new corn growers are about which hybrids are best, what equipment is needed and what yields to expect.

“When it comes to which corn hybrid to choose, first you need to decide if you are going for silage, grazing or grain,” Sommerfeld explains. “For silage, you want to cut that crop at about the R5 to R6 growth stage, which is about the half to three-quarter milk line stage, when the whole plant moisture is about 65 to 70 per cent. With that as your harvest time, choose a silage variety that fits with your area and that is about 150 to 300 heat units longer than your area’s heat unit rating, which is the long-term average corn heat units for your area.”

Corn heat unit (CHU) maps for the province are available on Saskatchewan Agriculture’s website.

“For grazing, you want your crop maturity to be at about the R3 to R5 stage, which is dough to half milk line, on the date of the first killing frost. In Saskatchewan, the long-term average for the first killing frost is around Sept. 15. So try to align your planting date and your first killing frost date so your corn will be at the dough to half milk line stage at the time of first frost. Select a silage/grazing hybrid that is about 150 to 300 heat units longer than your area’s rating.”

“Only certain locations in the province give consistently high enough heat units to allow grain corn to mature,” Peru says. Since grain corn needs to reach maturity before the first killing frost, pick a grain hybrid with a CHU rating similar to your area’s rating, if you’re planting by mid-May. For delayed planting, choose a hybrid with a lower CHU rating, reducing the rating by 100 for each week of delay after mid-May.

Peru suggests seeding corn into pulse stubble or cereal stubble. He adds, “Don’t seed into canola stubble. Corn heavily relies on mycorrhizal fungi to take up phosphorus, especially during the plant’s early growth stages. Canola isn’t a host to these fungi, so if you seed corn into canola stubble there won’t be sufficient levels of the fungi to allow the young corn plant to take up enough phosphorus to meet its needs.”

Corn has high nutrient needs, no matter whether it is grown for grain, silage or grazing. Peru says, “It’s recommended to have at least 150 to 180 pounds per acre of actual nitrogen (N) in the soil. Also, make sure you have enough potassium (K) and phosphorus (P). Soil tests are highly recommended. Make sure you have at least 35 to 40 pounds of phosphorus available, and each year apply around 10 to 15 pounds of potash, unless you have sufficient amounts based on your soil test.”

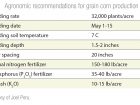

The current agronomic recommendations for grain corn are listed in the table below. The requirements are generally similar for silage and grazing corn, but a new project is underway to determine the optimal seeding rates and nitrogen fertilizer rates for silage and grazing corn under Saskatchewan conditions.

Corn production also requires some specialized equipment. “You need a row planter to grow corn. Corn doesn’t like to compete with itself so you want the seeds placed equally apart from each other,” Peru explains. For grain corn, you also need a corn header for your combine and a grain dryer. Grain corn is usually harvested between 20 and 27 per cent moisture content and then dried down to below about 13 per cent for long-term storage. Letting it dry down in the field below 20 per cent moisture increases the risk of harvest losses.

Overall, corn is a relatively high-input crop. The Irrigated Crop Diversification Corporation (ICDC) produces an annual booklet called “Irrigation Economics & Agronomics,” which includes worksheets for corn for grain, silage and grazing to help Saskatchewan farmers with irrigated land figure out if irrigated corn production makes economic sense for their farms. Peru adds, “For grain corn, you would probably want to aim for at least 150 bushels an acre to make a good profit.”

Filling agronomic information gaps

ICDC, which is based in Outlook, has been conducting corn-related research for a little over a decade. Its primary focus has been on trials to evaluate the performance of different corn hybrids under irrigated and dryland conditions. “We typically see a benefit to irrigation in both grain corn and silage corn,” notes Garry Hnatowich, ICDC’s research director.

The hybrid trials, which began in 2003, were initially a subset of the Alberta Corn Committee’s annual trials; the results are available at www.albertacorn.com. “For those trials, seed companies were invited to enter hybrids and to check off whether they also wanted trials conducted at Outlook, the only Saskatchewan site within the Alberta test,” Hnatowich explains.

However, Hnatowich found most of the hybrids being tested at the Alberta Corn Committee trials in Outlook weren’t actually available in Saskatchewan’s irrigation districts. So he, Peru and Sommerfeld got together to ask the corn retailers in the irrigation districts to submit their hybrids for the Outlook trials. As a result, starting in 2012, ICDC conducted an additional set of silage trials with these locally available hybrids.

ICDC stopped participating in the Alberta trials in 2016, so now all of its testing involves locally available silage and grain corn hybrids.

These Saskatchewan-oriented hybrid trials are funded by the province’s Agriculture Demonstration of Practices and Technologies (ADOPT) program. The results are published in Saskatchewan’s Crop Varieties for Irrigation guide.

Since 2003, average corn yields in the Outlook trials have been increasing. “The breeding efforts that the major companies are putting into corn are resulting in better yield stability,” Hnatowich explains. “The older hybrids tended to be longer maturing and often they were not ready to harvest when the first frost occurred. Over the last number of years, the days-to-maturity levels have been coming down significantly. Both for silage and grain, we are usually able to harvest prior to a frost event.”

Along with these Saskatchewan-focused hybrid trials, Hnatowich also emphasizes the need for made-in-Saskatchewan agronomic corn research. “In Saskatchewan, corn has been a very minor crop of interest, so we’ve got a bit of a learning curve in terms of corn agronomics compared to our sister Prairie provinces, Manitoba and Alberta. Manitoba gets the heat units, which we lack somewhat; it has a longer growing season that can accommodate corn. Southern Alberta has the heat units and it also has ‘Feedlot Alley,’ a concentration of beef production in the area that can utilize both silage and grain corn.”

He adds, “We can use the experiences of Alberta and Manitoba as a starting point for agronomic practices here, but there are refinements that need to be done for both grain and silage corn production in Saskatchewan.”

To get up to speed, ICDC’s corn agronomic research is starting with some basic considerations. As noted above, a new project is developing and refining recommendations for seeding rates and nitrogen rates for silage and grazing corn. ICDC and the Prairie Agricultural Machinery Institute are collaborating on this research.

“We don’t have a good handle on silage corn plant populations. So in our study we’re comparing 30,000, 40,000 and 50,000 plants per acre,” Hnatowich says. “In addition, we have very little information on fertility, in particular nitrogen fertility. So within those seeding rate experiments, we are also looking at three different levels of nitrogen fertilizer: 100, 150 and 200 pounds of nitrogen per acre (or kilograms of nitrogen per hectare). And on top of that, we are looking at two different hybrids at each site.”

The project is taking place at five sites in Saskatchewan: in Redvers, Yorkton, Outlook, Lanigan and Melfort. “At each site, we have different corn heat units, so we are using hybrids that we felt were best adapted to those climates. Typically they tend to be hybrids that retail outlets in the local area are selling,” Hnatowich explains. The Outlook site is irrigated; the other sites are dryland.

The project team will be examining silage yields, feed value and economics under the different treatments. The Western Beef Development Centre is conducting the feed testing. Project funding is from Saskatchewan’s Agriculture Development Fund.

Another agronomy project underway in 2016 involves grain corn. It is demonstrating the effect of a liquid starter fertilizer (6-22-2) on the yields of different hybrids under irrigation.

The idea is to use a small amount of fertilizer to boost early corn seedling growth. “Liquid phosphorus products are possibly more available to plants at early growth stages compared to granular products. Starter fertilizers improve early seedling development by providing available nutrients to the plant’s early root zone. Rapid crop establishment is desirable since plant development and yield can be influenced during early growth stages,” Peru, the project leader, explains.

The starter fertilizer treatments will be compared to untreated controls. Funded by ADOPT, this project is taking place on a 25-acre, pivot-irrigated field near Birsay in Saskatchewan’s Luck Lake irrigation district.

Looking ahead

Hnatowich, Peru and Sommerfeld all see potential for continued increases in corn production in Saskatchewan.

“I think there is great potential. With silage corn, livestock producers are perhaps looking at utilizing corn as a high value, high production, high-quality forage crop for either backgrounding animals or supplementing cows through the winter. So they are looking at using corn to increase the amount of forage production while maintaining the same number of acres on their farm. I think that is really one of the best fits for silage corn,” Sommerfeld says.

“With grazing corn, they can look at extending their grazing season, reducing some of the costs associated with keeping cattle in the yards during the winter. So again it is about increasing forage production without needing to increase their land base. I think that is what producers are really looking for – maximizing production but also trying to minimize their costs.”

“I feel Saskatchewan is a little behind the eight-ball when it comes to basic agronomics in corn production,” Hnatowich says. But, he adds, “The DeKalbs and the Pioneers in this world are certainly looking at Western Canada and Saskatchewan in particular right now as an expanded area for corn, with the promise of very early maturing hybrids that provide an acceptable level of yield. I suspect the corn companies might have target acreages for the province that might be optimistic. But each and every year we have a growing number of producers calling about silage corn production and there’s increasing interest in corn grazing in a lot of the areas.”

When it comes to grain corn, Peru emphasizes the need for continued advances in hybrid performance and agronomics. “We still need to do a lot of agronomic research to figure out the best way to grow corn in Saskatchewan. And we really need varieties that not only require low heat units but also produce high yields in order to make a profit because corn is a very high input crop that requires specialized machinery.”

Gallery photos courtesy of Joel Peru.