Features

Herbicides

Seed & Chemical

The state of herbicide resistance in Western Canada

The big story in 2017 was that canola surpassed wheat as the number one crop, and the most common rotation in Western Canada is canola-wheat, which certainly has implications for resistance management.

May 15, 2018 By Presented by Hugh Beckie Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Saskatoon at the Herbicide Resistance Summit Saskatoon Feb. 27-28 2018.

Group 1 and Group 2 resistant wild oats were found in 25 per cent of sampled Saskatchewan fields. The big story in 2017 was that canola surpassed wheat as the number one crop

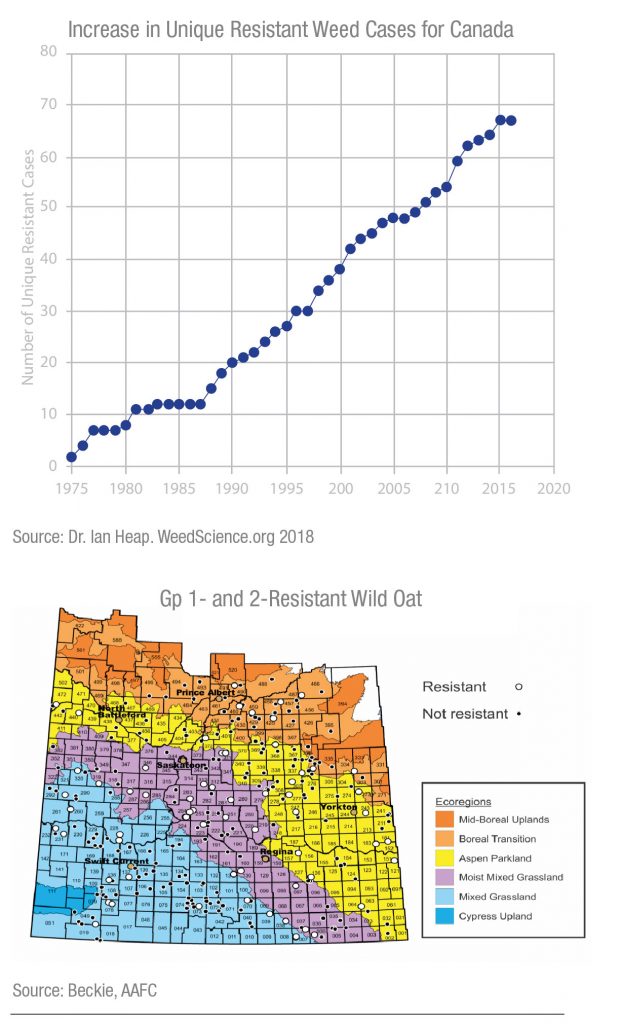

Group 1 and Group 2 resistant wild oats were found in 25 per cent of sampled Saskatchewan fields. The big story in 2017 was that canola surpassed wheat as the number one cropIn terms of unique resistant weed cases for Canada, 76 have been identified. Manitoba has seen a big jump and now has 30 cases. Saskatchewan has 22 and Alberta 23 cases.

I’ve been doing surveys since the first one in Saskatchewan in 1995 and since 2001 they’ve been random surveys. It takes three years to do a round because we do Alberta then Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. We’ve gone from 10.9 million acres with herbicide resistance in the first survey to 24.4 million acres in the second round from 2007 through 2009 and I would estimate we will clearly reach 38 to 40 million acres in the last survey completed in 2017. With 70 million cultivated acres in western Canada, over half the acres have herbicide resistant weeds.

The Saskatchewan situation

In the 2014-15 Saskatchewan Weed Survey 227 of 400 fields, or 57 per cent, had resistant weeds. This compares with 31 per cent in 2009 and 10 per cent in 2003. The screening is for just Group 1 and Group 2 resistance. We do plan to do the other herbicide groups but these two groups account for most of the cases. Overall, wild oat resistant populations were found in 65 per cent of the fields that were sampled.

Group 1 resistance wild oat was found at 59 per cent incidence. Group 2-resistant wild oats in Saskatchewan took quite a jump and were found in 32 per cent of fields sampled. That compares with only seven per cent in 2009 and four per cent in 2003. Obviously, growers are trying to manage Group 1 resistance by switching to Group 2 wild oat herbicides.

Multiple resistance, though, is where it gets challenging. Group 1 and 2-resistant wild oat was found in 25 per cent of fields versus only five per cent in 2009 and one per cent in 2003. We are seeing blanket resistance across all the Group 1 classes – the FOPs, the DIMs, and pinoxaden – and all the classes of Group 2 very commonly across the Prairies. We’re now at a stage where growers are asking which Group 1 or which Group 2 herbicide still works, if it does? For the wheat and barley growers in Western Canada, when you have wild oat resistant to all the Group 1, all the Group 2 – you cross out a lot of options. You cross out all of the post-emergence options.

We’ve been dealing with this multiple resistance for a very long time. In 1994, we documented four-way resistance – Group 1; Group 2; Group 8 (triallate) and Group 25 (Mataven or Flamprop-methyl, which is no longer on the market), and it was due to metabolic resistance. Recently, University of Alberta graduate student Amy Mangin, who’s now at the University of Manitoba, documented five-way resistance in wild oat. We had known previously it was Group 1 and Group 2-resistant, but we found it was also resistant to triallate, Group 8; and then, unexpectedly, to sulfentrazone, Group 14; and pyroxasulfone, Group 15. Even though this population clearly hadn’t been exposed to Group 14 or 15 herbicides, again, it was due to metabolic resistance.

Looking at green foxtail, 31 per cent of the fields sampled had herbicide resistance. Seventeen per cent of the fields had Group 1 resistance, versus 14 per cent in 2009 and none in the 2003 survey. The most recent survey is the first to document Group 2 resistance, so it’s paralleling the wild oat’s story, although at a slower pace. We also had two fields with multiple resistant green foxtail to Group 1 and Group 2 – again, the first time.

Cleavers, I was a bit surprised that it really hadn’t changed in incidence over the last survey at around 20 per cent of fields sampled. Certainly, northeast of Saskatoon, there’s an epicentre of Group 2 resistant cleavers. Group 2 cleavers is problematic especially our pulse growers. If look at options in field pea, whether it’s Group 1 or Group 2 wild oat or Group 2 cleavers, the options become quite limited.

Group 2-resistant wild mustard hasn’t changed in incidence at 25 per cent. It was first recorded in the 2009 survey. Central

Saskatchewan is where most of it is. For lentil growers in Central Saskatchewan, if you drive from Rosetown down to Swift Current, it’s all Group 2-resistant wild mustard.

Group 2-resistant stinkweed was first documented in the recent Saskatchewan survey on 14 per cent of fields surveyed. It was also the first survey to document shepherd’s purse resistant to Group 2 herbicides on three fields or 23 per cent incidence, mostly northwest of Saskatoon.

Finally, in the Saskatchewan survey, we are starting to see some redroot pigweed resistance to Group 2, although, certainly, the amaranthus resistance is certainly not like it is with the waterhemp or Palmer amaranth in the Midwest United States.

The Manitoba situation

In the 2016 Manitoba survey, we had 102 out of the 151 with herbicide resistance, or 68 per cent. The majority of growers are dealing with resistance. If you look at herbicide-resistant wild oats, 79 per cent of fields had herbicide resistant wild oats, with 78 per cent of them resistant to Group 1 compared to 55 per cent incidence 2008, and 40 per cent in 2002. Group 2-resistant wild oat took a big jump, similar to what it did in Saskatchewan, with 43 per cent incidence versus 18 per cent in 2008 and 12 per cent in 2002. Multiple resistant Group 1 and Group 2-resistant wild oat were found on 42 per cent of fields, versus 13 per cent in 2008 and eight per cent in 2002. Manitoba continues to lead the pack in terms of incidents of multiple resistance.

Almost half of the fields had green foxtail resistance. Forty-four per cent were Group 1 resistant. That’s pretty stable since 2008. Group 2 resistance was at six per cent, and 2016 was the first survey to pick up Group 2 resistance. Multiple resistance to Group 1 and 2 was found on only one field near Brandon.

Yellow foxtail was the surprise of the 2016 Manitoba survey. We found 42 per cent of the fields with resistance in yellow foxtail – 32 per cent of that was Group 1. This was the first case in Canada to document resistance in this cousin to green foxtail. Group 2 resistance was found on 17 per cent of fields surveyed, and Group 1 plus Group 2 resistance on four fields. This resistance came out of nowhere since it wasn’t documented in the 2008 survey.

We found Group 2 resistant barnyard grass on three fields — the first documented cases of resistance in the 2016 Manitoba survey.

There was just a sprinkling of broadleaf weed resistance with a few cases of cleavers, wild mustard, redroot pigweed and shepherd’s purse resistant to Group 2 herbicides.

Alberta’s status

We started to screen the 2017 Alberta survey of 250 fields – the last survey was in 2007. The results will be coming out in 2018. We also did a 2017 post-harvest glyphosate-resistant kochia and Russian thistle survey at 330 sites. We had 305 sites of viable kochia, 31 sites of Russian thistle. We compared these results to the recently completed Saskatchewan and Manitoba surveys.

In the 2013 Saskatchewan survey, five per cent of the sites had glyphosate-resistant kochia, mainly associated with chemfallow in West/Central Saskatchewan. In Manitoba in 2013, we only had two sites in corn and soybean in the Red River Valley, although the University of Manitoba has identified a few more sites. We’ll be surveying Manitoba again 2018 using the similar methodology, including a few other suspected glyphosate-resistant weeds. We’ll be doing

Saskatchewan in 2019.

By comparison, in Alberta in 2012, we had 13 of 309 sites with glyphosate-resistant kochia, or five per cent – in the three counties of Warner, Taber, and Vulcan. From the 2017 post-harvest survey in Alberta, we’ve screened about 77 per cent of the kochia samples and found 54 per cent of the sites with glyphosate-resistant kochia. We’ve jumped from five per cent to 54 per cent in five years. Most of these fields were not chemfallow. We found it in all kinds of fields.

For these Alberta kochia samples, the next step is to screen with Group 4 resistance, and so time will tell what the level of Group 4 resistance is. And, of course, all of these kochia samples are Group 2 ALS-resistant. We’ve lost Group 2 and we’re losing glyphosate. If we lose Group 4 for kochia, southern Alberta is not going to look the same as it is today.

When we wrote up the paper for these surveys, I stated: “The ease of mobility of resistant alleles from field to field demands a collective regional response in proactively or reactively managing this multiple-resistant weed biotype.” Clearly, we’ve collectively failed to slow down the spread of glyphosate-resistant kochia.

There is a need for a Group 4 kochia action committee, but we can’t just include researchers because we are all the same people talking to each other. We have to include all levels of government, the administrators of the municipal districts or counties or municipalities. We have to include provincial government, federal government. We need to include all the stakeholders if we want to make an impact against Group 4 resistance.

Top 10 herbicide-resistant weed management practices

On a positive note, a retired AAFC colleague, Neil Harker, and I wrote a paper with “Top 10 Herbicide-Resistant Management Practices.” The number one practice was crop diversity.

- 10. Maintaining a database: invaluable reference

- 9. Strategic tillage: If, where, or when needed

- 8. Field and site-specific weed management – one size may not fit all

- 7. Weed sanitation: border control and slowing herbicide resistance dispersal

- 6. In-crop wheat-selective herbicide rotation – combating non-target-site-resistance

- 5. Herbicide Group rotation – avoid back-to-back in-crop Group 1 or Group 2

- 4. Herbicide mixtures/sequences – better than rotations

- 3. pre- and post-herbicide scouting – know your enemy

- 2. Competitive crops and practices that promote competitiveness –natural biological control

- 1. Crop diversity

What are missing from these top 10 practices are incentives for growers to implementation. Stuart Smyth, myself, and others are co-authoring a paper that will be coming out shortly arguing that crop insurance is the best vehicle to incentivize and facilitate best pest management practices. We need government public policy to incentivize growers, and, really, governments have been missing in action for the last 30 years, in terms of sitting on their hands and doing nothing.

In our management surveys with growers, we are starting to see some of the weed management messages get out. I think the message is that growers . . . whether themselves or with crop consultants or with agronomists, are starting to scout their fields; know what their enemy is before they implement treatments. If you don’t know what’s out there, how can you effectively manage that, whether it’s resistant or not?

I was very encouraged to see quite a change from our previous grower management questionnaire results. We have seen a big shift over the last 10 to 15 years in terms of what growers . . . at least what they perceive as being effective to manage resistance. What we did find interesting though was that growers specifically dealing with resistance, these were the four practices that they do preferentially, more so than growers without resistance: crop rotation, herbicide site of action rotation, tank mixing, and a burndown. Of course, when you lose the effectiveness of your post-emergence, you have to rely more on a burndown, which will delay the selection pressure when you do have to come in with a post-emergence.

When we looked at the Manitoba results, the only thing that was really different was that in Manitoba, growers are reverting to much more tillage to manage resistance.

When we asked growers the cost of weed resistance – a combination of yield loss and increased herbicide cost – it averaged $12/acre in Saskatchewan, and $11/acre in Manitoba.

Overall, growers are implementing some of the best management practices if they fit in to their operations, but we need new tools, too. We also need all levels of government to incentivize – not regulate but incentivize – these best management practices because the status quo right now is not moving the ball fast enough in the right direction.

For more stories on this topic, check out Top Crop Manager’s Focus On: Herbicide Resistance, the first in our digital edition series.

Print this page