Features

Agronomy

Other Crops

Seeding canola into tall stubble

Seeding canola into tall standing stubble doesn’t always produce higher yield, and carries some risk in some geographic locations, but under the right conditions, the practice can work.

Building on research conducted by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada scientists Herb Cutforth and Brian McConkey at Swift Current, Sask., University of Manitoba (U of M) graduate student Michael Cardillo expanded the research to look at tall stubble effects at 11 site-years across Western Canada.

“The climate is changing, and with increasing world population, we need to look at management practices that farmers can very easily implement that can help them produce more food,” Cardillo says. “Cutforth’s work at Swift Current showed that leaving stubble taller was very successful in improving the microclimate in tall stubble and producing higher yield under semi-arid conditions. We wanted to see if it would work for canola in a larger eco-climate across the Prairies.”

Cardillo’s research, conducted with Paul Bullock and Rob Gulden of the U of M, Aaron Glen of AAFC Brandon and Cutforth, included four locations in 2011 at Swan Lake, Man., Indian Head and Swift Current, Sask., and Grimshaw, Alta. In 2012, an additional three sites were added at Kenton, Man., and Falher and Lethbridge, Alta. The sites provided a broad range of eco-districts, climatic conditions and soil types.

Cereal stubble heights compared were 20 cm (7.9 in) and 50 cm (19.6 in). In some cases, the stubble was cut to height in the fall. In other cases, the stubble was left tall over winter, and then cut to the shorter height in the spring ahead of canola seeding. At some sites, the tall stubble was flattened as a result of lodging from over-wintered snow, strong winds or mechanical damage during seeding. This created an additional factor to consider, and so the sites were further classified into whether the tall and short stubble treatments were intact or damaged.

“One of the risks farmers have to assess is whether the tall stubble might be flattened by snowfall, and how that will impact their ability to seed, and the potential for cooler, wetter spring soils,” Cardillo says.

The snowpack was assessed at Swan Lake and Indian Head in both 2011 and 2012 because the tall and short stubble was established in the fall. Overall, Cardillo says, as expected, the tall stubble had higher snow water equivalent than the short stubble.

“Historically, 30 per cent of precipitation falls as snowfall, so in a dry year, tall stubble can help recapture moisture loss coming into the spring,” Cardillo says.

In 2011 and 2012, growing season precipitation was above average at 10 of the 11 site-years, with generally wetter conditions earlier in the growing season and a gradual reduction in rainfall to below-average levels.

Stand establishment and yield

Canola emergence and plant populations were compared across intact and damaged sites for both tall and short stubble. Plant populations were greater in intact tall stubble than damaged tall stubble. But for short stubble, the plant population was significantly higher in the damaged stubble. On the intact stubble sites, there was no significant difference in plant populations between tall and short stubble.

“The wet spring conditions provided good seedbed conditions in the intact stubble treatments, and resulted in good stand establishment at the intact stubble sites,” Cardillo says.

Canola yields were significantly higher in the intact stubble rather than the damaged stubble, for both tall and short treatments. Cardillo explains this is likely due to the soil warming and drying more quickly in the intact stubble than on the sites where the stubble was flattened on the ground. The tall intact stubble sites also had significantly higher yield than the short intact stubble treatments.

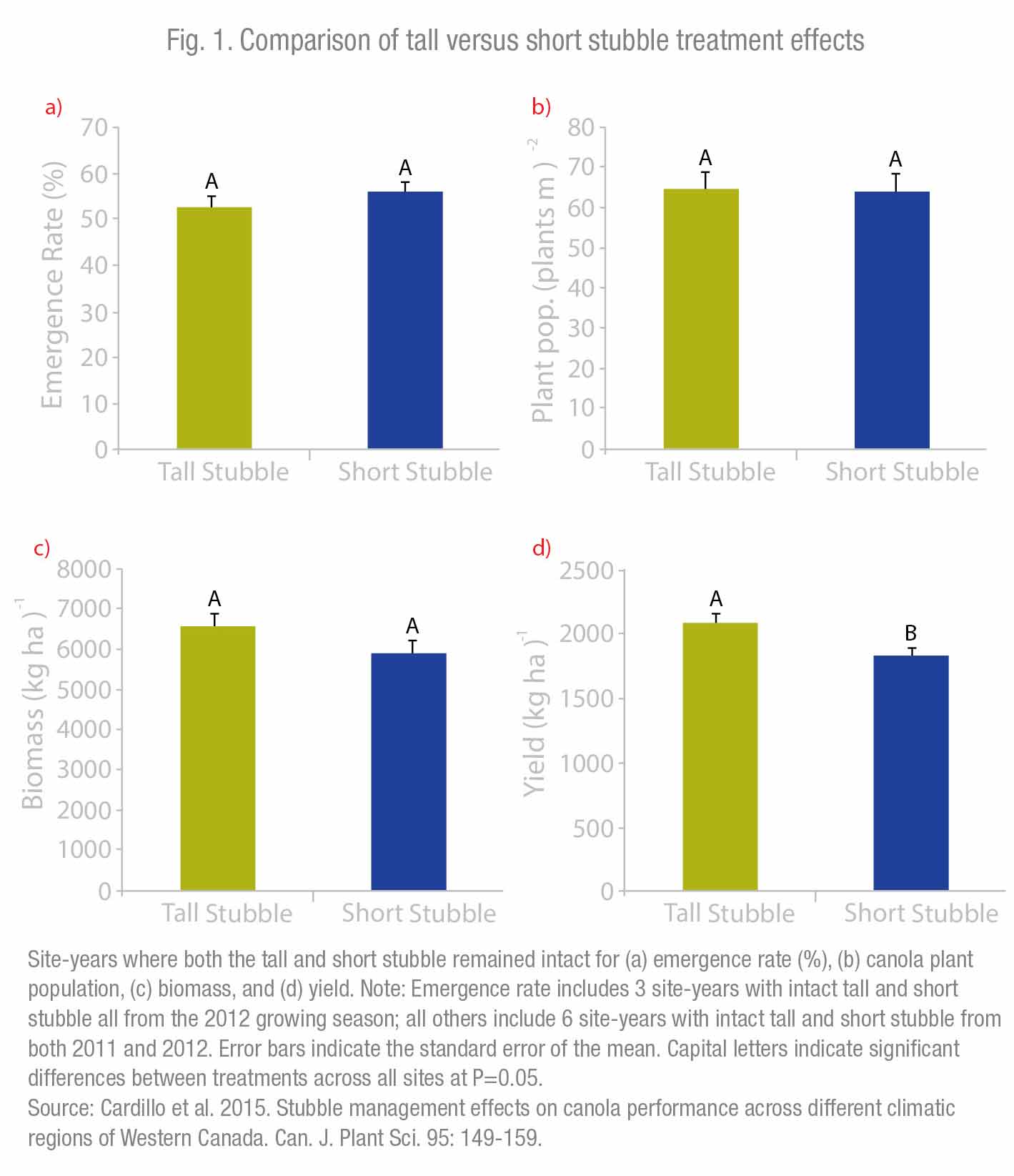

“There was enough moisture stress later in the growing season to provide an advantage to the tall stubble. The tall stubble provided a better microclimate with reduced evaporative water loss, which resulted in higher yield,” Cardillo explains. (See Fig. 1.)

Risk vs. reward

Cardillo says results of the research show both the risk and rewards of leaving stubble tall prior to seeding canola the following spring. In areas with typically heavier snowpack and wetter spring conditions, tall stubble may be flattened in the spring, slowing soil warming and making seeding difficult. Short stubble may also be flattened and suffer lower yields as well, but with less straw to contend with short stubble may present fewer seeding challenges.

In areas where snowfall is lower and growing conditions drier, the potential for higher canola yields when seeded into tall stubble is well proven by Cutforth’s and Cardillo’s research. In these areas, tall stubble will usually remain standing overwinter, thus capturing more snow and providing a better microclimate, resulting in higher yield.

“Leaving stubble tall is a nice useful tool for farmers. But it isn’t written in stone. You don’t have to do it every year. It’s a judgment call. Farmers can assess soil moisture conditions at harvest and decide if they want to take the risk of leaving stubble high. And you don’t have to cut at 50 cm. Maybe there is less risk of lodging at 30 cm, or maybe a greater advantage at 60 cm. It is a potentially good management practice that has flexibility for many farmers,” Cardillo says.

February 17, 2016 By Bruce Barker

Intact stubble (left) produced significantly higher canola yields than damaged stubble (right). Seeding canola into tall standing stubble doesn’t always produce higher yield

Intact stubble (left) produced significantly higher canola yields than damaged stubble (right). Seeding canola into tall standing stubble doesn’t always produce higher yield