Features

Agronomy

Seeding/Planting

Reconciling canola seeding rate and seed size

In an effort to reduce canola seeding costs, some growers are cutting seeding rates from five pounds an acre to four and even three pounds per acre. At the same time, hybrid canola seed size has been increasing, resulting in the possibility of inadequate stand establishment. To better understand the interaction of seed size and seeding rate, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) research scientist Neil Harker at the Lacombe Research Centre led a study comparing two seeding rates with four canola seed sizes.

“Relatively high seed costs have prompted growers to seed canola at suboptimal rates,” states Harker in his journal article, Seed size and seeding rate effects on canola emergence, yield and seed weight. “As seed costs increase, growers are pressured to reduced seeding rates; the combined effect of reduced seeding rates and the trend for larger seeds can threaten canola yield potential.”

Harker’s research was published in the January 2015 issue of the Canadian Journal of Plant Science: Harker, K. N., O’Donovan, J. T., Smith, E. G., Johnson, E. N., Peng, G., Willenborg, C. J., Gulden, R. H., Mohr, R., Gill, K. S. and Grenkow, L. A. 2015. Seed size and seeding rate effects on canola emergence, development, yield and seed weight. Can. J. Plant Sci. 95: 1-8.

In 2013, a Canola Council of Canada (CCC) survey found that approximately one-half of western Canadian canola growers had stand establishment of less than the minimum of at least 40 plants per square metre required for optimal yields. In previous research, Harker also found that across Western Canada, only about 50 per cent of canola seeds emerge. This highlights the importance of understanding the interaction of seeding rate and seed size, and why 50 per cent of canola fields have inadequate stand establishment.

Harker’s research partially builds on research done by AAFC researcher Bob Elliott at the Saskatoon Research Centre in the late 1990s. Elliott’s research provides an indication of how canola seed has grown in size. He classed small canola seed at 1.9 g/1000 seed, large at 4.0 g, and very large seed ranged from 4.2 to 4.7 g. Today, seed weights greater than 6.0 g/1000 are not uncommon. Using relatively small seed, Elliott found that canola emergence and yield increased as seed size increased. Other studies, though, did not find the same correlation.

“With continual canola improvement and cultivar changes, we felt it necessary to re-examine seed size effects on growth and yield,” Harker says. “Our hypothesis was that several canola growth, productivity and quality traits would improve as seed size increased.”

Harker’s 2013 research project looked at the effect of two canola seeding rates and a range of current canola seed sizes on crop emergence, growth, yield and quality at nine western Canadian sites. Each site was direct seeded into wheat, barley or oat fields, and agronomic inputs were applied based on standard recommendations. Canola was seeded at a target depth of 0.4 to 0.75 inch deep in 7.5 to 11.8 inch row spacings. Weather patterns were similar to long-term averages at most sites.

Canola seeding rates were 75 and 150 plants per square metre. Canola seed sizes based on average 1000-seed weight were 3.96, 4.6, 4.8 and 5.7 g per 1000 seeds, and one un-sized treatment at 4.4 g. Preliminary germination tests found all seed sizes exceeded 97 per cent.

Yield unaffected

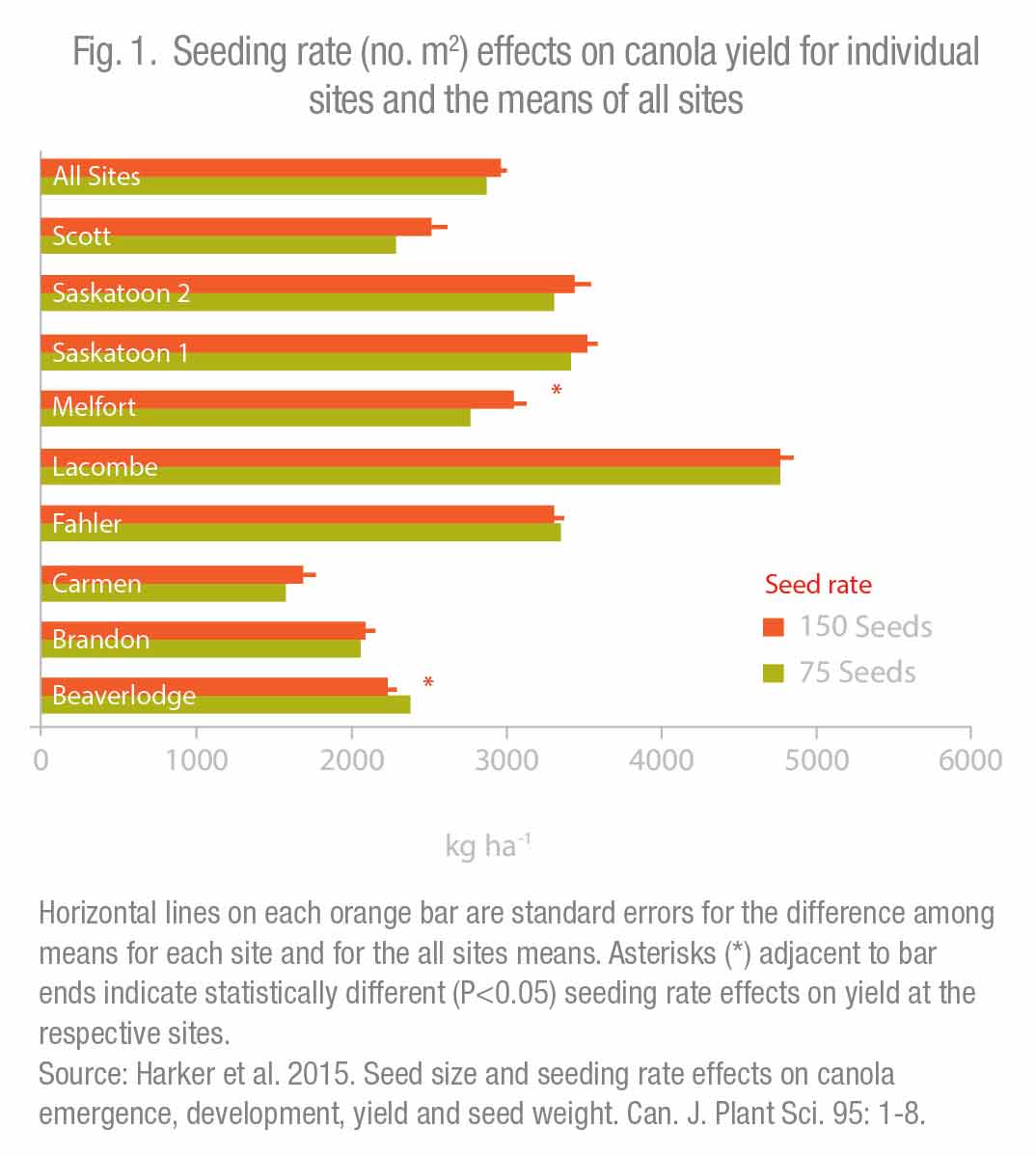

Neither seeding rate nor seed size had a significant effect on yield. In addition, seeding rate did not interact with seed size for any factor measured.

Emergence percentage was 55 per cent for both seeding rates. This resulted in an effective stand establishment of 35 plants per square metre for the 75 plants per square metre seeding rate, and 67 plants per square metre for the 150 plants per square metre seeding rate. The lower seeding rate was close to the optimum stand establishment recommended by the CCC of 40 plants per square metre. With near normal growing conditions, the good stand establishment likely explains why seeding rate did not impact yield. (See Fig. 1.)

While the higher seeding rate did not increase yield, it did result in increased early crop growth that helped the crop compete with weeds better. Higher seeding rate also resulted in the crop coming into flower sooner and decreased days to maturity. It also produced larger seed with higher oil content. All can be important factors in canola production over the longer term – flowering before high summer temperatures; avoiding early frosts; managing herbicide resistance.

Increasing seed size did not have any effect on emergence, seed quality or yield. It did, though, increase early season growth. Days to flower and days to end of flowering were also decreased with increasing seed size. Increasing seed size resulted in increased 1000 seed weight at harvest.

While not measured in this study, other researchers have found that seedlings from larger seed are less susceptible to flea beetle damage.

“Greater biomass from large seeds increases crop competition with weeds and also hastens flowering, shortens the flowering period and reduces the risk that canola will be exposed to high temperatures that can negatively impact flowering and pod development,” Harker reports.

The lessons found in the research supports the need to establish seeding rates based on plant populations and 1000 kernel weight, which can be done using an online seeding rate calculator found on various government websites. While 40 plants per square metre is the minimum recommended, the CCC recommends targeting at least 70 healthy, surviving plants per square metre to maintain yield potential for canola. This allows for some plant mortality due to post-seeding stresses such as frost, disease and insects.

February 17, 2016 By Bruce Barker

Optimal stand establishment is 40 plants per square metre. In an effort to reduce canola seeding costs

Optimal stand establishment is 40 plants per square metre. In an effort to reduce canola seeding costs