Features

Agronomy

Soil

Farming in nature’s image

Hard economics and one man’s experience may be influencing a number of farmers to reconsider their farming practices this growing season, for the benefit of their soils.

Ray Archuleta, a conservation agronomist with the United States Department of Agriculture, is working to convince progressive farmers to adopt some very old philosophies. For those unfamiliar with him, Archuleta’s biggest complaint with modern agriculture is that too much focus is put into working against nature and not enough on working with it. So, he’s travelling the continent, asking audiences to name peers or mentors who taught them how to farm “in nature’s image” and even among organic farmers, he says silence is far too common. “When industrial agriculture kicked in, we lost the art and science of how to work with the natural ecosystem,” he laments. The most critical of these ecosystems, he says, is the soil itself.

Soil is alive and too many people in the industry have forgotten that, according to Archuleta. “There are textbooks that teach the soil is just a medium - and that’s ridiculous,” he says. “To me, the most important component of soils is the living part.” Arthropods, mesofauna, springtails, and earthworms, these organisms make the dynamic properties of soil ecosystems. Protecting their habitat and feeding them will improve soils in just two to five years, when managed correctly he says. Any farmer unsure of that can take a shovel to the nearest woodlot, dig up a soil sample, and compare it to another sample from any field. “Your woodlot is going to look magnificent,” he says.

Archuleta takes his own demonstrations further by dropping soil samples in a clear container full of water. “Soil that’s been tilled will explode in the water and that means the biotic glues and cementing agents have been oxidized off,” he explains. “Good healthy soils should hold together as water rushes in to fill pore spaces.”

Reducing tillage, along with diversifying crop rotations, growing diverse cover crop mixes, graze like the Bison, and adding organic components (manure, compost, residue), are five ways Archuleta says farmers can get soil in the field that’s more like the one found in woodlots. In other words, mimic nature. Nature does not till, it is diverse, covered 24/7 with green living plants or armor and nature does not farm without animals. This is “biomimcry” or “ecomimcry” (mimicking biology and ecology).

“I’m a huge advocate of no-till,” he says. “Once you understand how elegant and complex soils are, you don’t want to till.”

Although he admits the climate and temperature found in Ontario is more forgiving than in hotter, drier regions, he insists the disorder caused by even some tillage will stress the natural ecosystem found in the soil. Archuleta doesn’t even recommend tillage for incorporating compost or manure into the soil, even though adding organic material is one of his five recommended practices. You must limit surface disturbance. Injection is fine, but disking in manure is destructive to the soil.

“I don’t want manure incorporated into my soil,” he says. “When you incorporate the manure in, you wake up r-strategists – opportunistic bacteria that break up aggregates and release nitrates – you bring weeds to the top, and you think you saved your nitrogen, but you just made it worse.” He advises farmers to let the system take care of itself and work to eliminate things that stress the natural system like tillage, insecticides, herbicides, fungicides and chemical based nitrogen. Trying to farm using “ancient sunlight” (petroleum based inputs – diesel, chemical fertilizer, and pesticides) will make a farmer go broke, Archuleta says, but trying to farm only using “new sunlight” can save a lot of money.

“No tillers cut their energy costs by 70 per cent in the first year,” he says. “Nobody talks about that.”

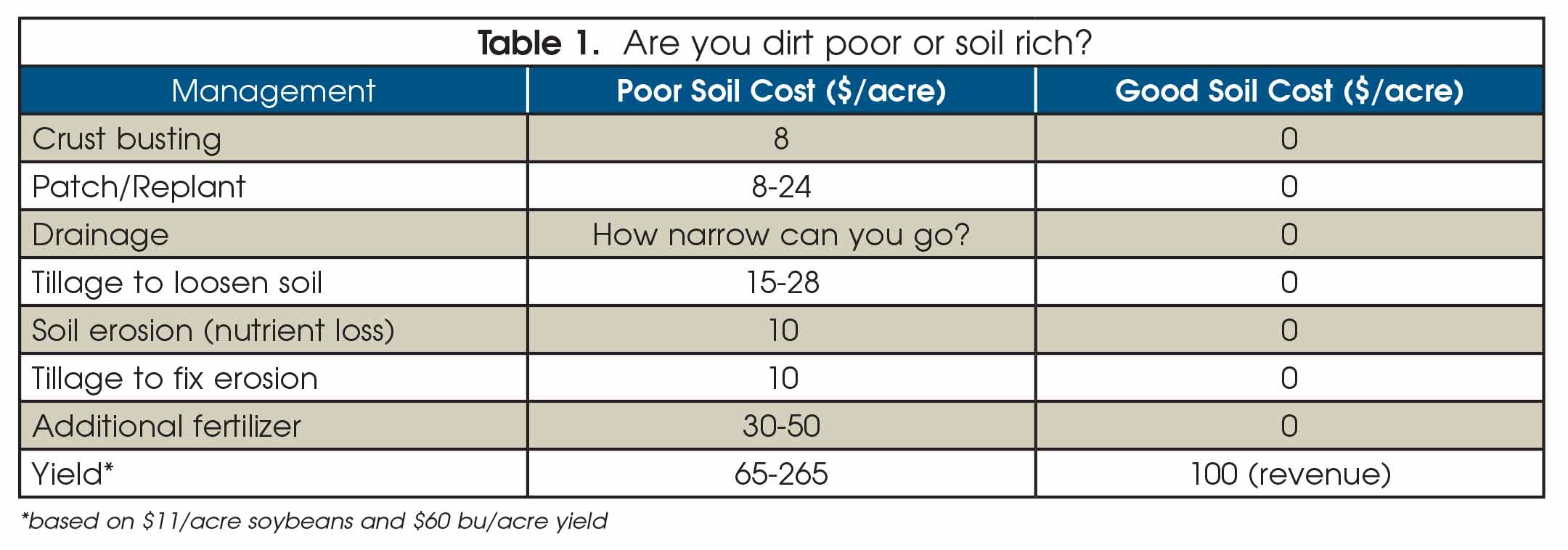

But Anne Verhallen, soil management specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) and her colleague, Adam Hayes, actually have been talking to farmers about the cost of tillage (see Table 1). “I think the hard economics of soil health are really important to our growers,” Verhallen says. “Soil health goes beyond the warm and fuzzy.”

Verhallen adds the cost of not having good soil health is something many farmers don’t figure in, but can calculate for themselves. “If you’re having to split your tile because your soil structure has degraded and you’re not getting good internal drainage of water, there’s a cost to that,” she offers as an example.

Even though the data is pretty clear, Verhallen says Archuleta is far more severe in tillage discussions than she and her co-workers are, but she believes Archuleta pushes the bar a little higher. “He might take it a little further than we do but he’s still saying the same things,” she says. The ultimate point is that results are what matter, not excuses. For instance, Verhallen says one common excuse for refusing to adopt no-till is increased slug pressure, a concern for most Ontario soil types. “The guys who are trying [no-till] acknowledge there are slugs and feeding, but not enough to knock out the population.” In her opinion, it’s just one of those things farmers need more experience with, but that’s something Archuleta can share.

“Ray’s got such fervour, such enthusiasm for his topic but he’s also got some really good observations,” Verhallen says. “We brought Ray [to Ontario] to challenge producers to think outside the box, to think about their soil in a different way.”

September 3, 2015 By Amy Petherick

Ray Archuleta challenges producers to work with nature Hard economics and one man’s experience may be influencing a number of farmers to reconsider their farming practices this growing season

Ray Archuleta challenges producers to work with nature Hard economics and one man’s experience may be influencing a number of farmers to reconsider their farming practices this growing season