Features

Insect Pests

Wireworm ID 101

A new guide illustrates the species variability of wireworms on the Prairies.

June 10, 2022 By Jennifer Bogdan

To effectively manage one’s enemy, you have to know one’s enemy. But it’s pretty hard to develop a management strategy if you don’t know what you’re looking at in the first place. Enter the wireworm, the larval form of click beetles, native insects that survived on the grasses of the natural Prairie landscape long before large-scale crops ever became a part of their ecosystem. As the grasslands were broke and replaced with annual crops, the wireworms learned to feed on their new host plants, ever adaptable as nature often is. More than a century later, managing this insect remains a challenge for farmers. Luckily, there’s a team of entomologists, and their new guide, for that.

Haley Catton, research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), led a project to develop a wireworm guide specific to the Prairie provinces. The final product, Guide to Pest Wireworms in Canadian Prairie Field Crop Production, was released in 2021, thanks to funding provided by Alberta Wheat Commission, Western Grains Research Foundation, and AAFC.

Catton explains the purpose behind this new guide: “Wireworms have been a common pest in Western Canada for a very long time. There has been over 100 years of research on wireworms on the Prairies but all of it was in the scientific literature, which is not easily accessible to most people. There was also a lot of confusion with wireworms and a lack of good photos for people to understand what is and what isn’t a wireworm, as well as the differences between wireworm species. I wanted to bridge this information gap in plain language and the result is the new wireworm guide. This book is really us standing on the shoulders of giants – we took all of the extensive research available, beginning in the Prairies in the 1920s, and summarized it into one resource that is easy to read, is full of excellent photos and visuals to help with identification, and is freely accessible to everyone.”

Get to know the two main species

The two main wireworm species on the Prairies – Hypnoidus bicolor (left) and Selatosomus aeripennis destructor (Prairie grain wireworm, right). Photo courtesy of J. Saguez, CÉROM, excerpted from Guide to pest wireworms in Canadian Prairie field crop production (2021).

Of the thousands of wireworm species across the globe, at least 182 of them reside in the Prairies. Only 11 of these species are considered pests, with just two being responsible for the majority of the damage – Hypnoidus bicolor (no common name) and Selatosomus aeripennis destructor (Prairie grain wireworm).

“Our two main species almost always appear in the field together, especially in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Different fields will have different species that are dominant, but you almost never find just one species per field. Research has also found regional differences in species as well. For example, there are very few populations of Selatosomus (Prairie grain wireworm) in Manitoba but this species is abundant in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Also, irrigated fields are more likely to have a third species present, Limonius californicus. And, interestingly, near Magrath in southern Alberta, a less common species, Hadromorphus glaucus, exists in a geographical pocket by itself – a species that we still know very little about,” Catton says.

Catton emphasizes the importance of knowing which wireworm species are in fields because the different biology of each species can potentially affect the management strategy used in the future. “First of all, it’s critical to know that what you find in the field is actually a wireworm. If it is, we have new methods that we are developing that are specific to each wireworm species, such as in the area of pheromone monitoring. As well, some species are known to be more damaging than others so there may be different economic thresholds for the different species, although this is not known yet. For any integrated pest management (IPM) strategy, you need to know what your pest is so you know what its weaknesses are, which is why we’re working to develop individual IPM strategies tailored to each of the most common pest species,” she says.

Of the two main Prairie wireworm species, the Prairie grain wireworm is much larger than Hypnoidus bicolor. Size is a helpful feature when full-grown wireworms are found, but a younger Prairie grain wireworm can be the same size as a full-grown Hypnoidus wireworm, so then attention needs to be focused on the rear end (Figure 1). To confirm the wireworm species, a hand lens or magnifying glass is needed to clearly see the shape of the “caudal notch” and its surrounding “prongs” on the last abdominal segment. The new wireworm guide provides clear photos and descriptions of the distinguishing features on the final abdominal segment for each of the main Prairie pest wireworms.

If examining caudal notches aren’t for you, samples of wireworms can be submitted to provincial labs or directly to Catton’s lab for species identification.

Things often confused for wireworms or click beetles

Figure 2. Wireworm (A), Crane fly larva (B), Stiletto fly larvae (C). Photo courtesy of Jennifer Bogdan.

When digging around in a field, a lot of wormy creatures can be found, leading to the question: Is that a wireworm?

“In short, a wireworm is usually yellow and hard-bodied. They have three pairs of legs – no more, no less – and typically has some kind of notch in its rear end. Anything else can be an “imposter,” some of which are beneficial insects. Knowing the most commonly encountered insects that can be mistaken for wireworms and their click beetle adult forms will go far in determining if you actually have a wireworm issue in your field in the first place. This is why we included a section on these different look-alike insects in the guide,” Catton explains.

Crane fly larvae (Figure 2B) are chubby and dull in colour compared to the slender, often shiny wireworm (Figure 2A). As fly larvae, they do not have legs like wireworms do, and their rear end has feathery projections called papillae.

Stiletto fly larvae (Figure 2C) are skinny with a shiny, whitish body and a red head capsule. Like other fly larvae, stiletto fly larvae have no legs. These larvae thrash around wildly when disturbed and are a predator of wireworms, so finding them in the field is a good thing.

Figure 3: Wireworm (A), cutworms (B). Photo courtesy of Jennifer Bogdan.

Cutworms (Figure 3) are much chubbier than wireworms and curl into a tight C-shaped ball when disturbed. While cutworms have three pairs of true legs like wireworms do, they also have multiple pairs of fleshy prolegs along their abdomen (wireworms do not).

Carabid (ground beetle) larvae have three pairs of true legs like wireworms do, but because they are a predator, carabid larvae have a large set of mandibles used for catching prey. They also have two long, forked projections on their rear end which wireworms do not have. These are beneficial insects and may hunt wireworms in the soil.

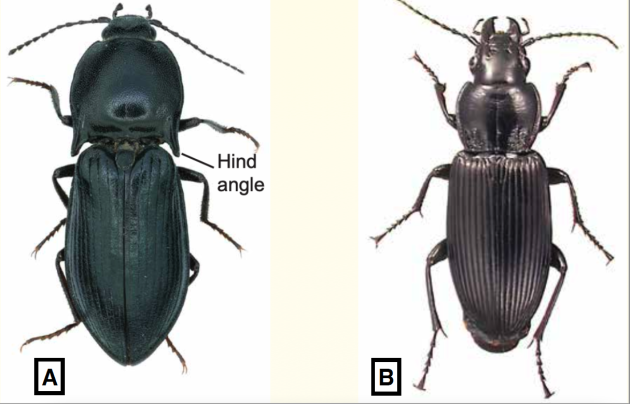

Click beetles, the adult form of wireworms, have two points (“hind angles”) on the back of their pronotum, making this segment look like the Batman mask. Click beetles get their name from the sound they make when flipping from their back onto their feet again. Ground beetles look very similar to click beetles, but they do not have the hind angles that click beetles do, and they have large mandibles (Figure 4). Like their larval forms, ground beetles are a beneficial predator on the Prairies.

Click beetles, the adult form of wireworms, have two points (“hind angles”) on the back of their pronotum, making this segment look like the Batman mask. Click beetles get their name from the sound they make when flipping from their back onto their feet again. Ground beetles look very similar to click beetles, but they do not have the hind angles that click beetles do, and they have large mandibles (Figure 4). Like their larval forms, ground beetles are a beneficial predator on the Prairies.

Insect publications available

Printed copies of the new wireworm guide are available for free in English and French, while supplies last, by contacting Haley Catton at haley.catton@agr.gc.ca. Digital copies of the wireworm guide, along with other helpful insect identification resources, can be downloaded in both official languages for free at the links below:

Guide to Pest Wireworms in Canadian Prairie Field Crop Production

Cutworm Pests of Crops on the Canadian Prairies

Field Crop and Forage Pests and their Natural Enemies in Western Canada