Features

Fungicides

Seed & Chemical

When to stop spraying fungicides

Disease attacking the flag and penultimate leaves can cut into yield. Photo by Bruce Barker.

A wetter-than-normal growing season produced a bumper crop of yield and disease in 2013. While fungicide application provided an economic return for many growers, there are limitations on when to stop fungicide application. Part of the decision is timing, and part is related to label restrictions.

Faye Dokken-Bouchard, provincial specialist – plant disease with the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture, says the spray decision needs to be carefully considered, and many factors go into whether to spray or not.

“The decision whether to spray or not continues to raise more questions than answers,” says Dokken-Bouchard. “What if disease wasn’t noticed until after the proper application period passed? How late is too late to spray? When are multiple fungicide applications warranted? Will the resulting yield benefit cover the application costs?”

Crop considerations

When assessing fungicide application, several crop factors influence the decision. Crop variety and disease rating are important considerations, says Dokken-Bouchard. The disease resistance rating and the realistic expectations for the type of crop or specific variety under current conditions are important factors to consider.

Chickpea varieties currently grown commercially in Saskatchewan have fair ascochyta blight ratings, but resistance weakens as plant development nears the flowering stage, so adequate scouting at this stage is important. Cool, moist environmental conditions favour the disease, and if these conditions persist early in the growing season, the disease symptoms can occur much earlier than the flowering stage. This is especially true on chickpea grown outside the Brown Soil zone (the area of best adaptation) or on heavy textured soils such as clay and clay loam, so early fungicide application may be required. Subsequent monitoring of crop and disease will help guide the spray decision later in the season.

Blackleg may appear on otherwise resistant canola varieties if they have been damaged (by hail, for instance). In addition, new races of blackleg are evolving, and varieties that were previously rated as resistant are showing evidence of disease. In this case, little research exists on whether a fungicide application on a R-rated variety would provide an economic return, so growers and crop scouts must consider the risks/rewards carefully.

Stripe rust in wheat has become more of a concern in recent years. Randy Kutcher at the University of Saskatchewan initiated a large project assessing a combination of varietal research and fungicide timing options in 2012. Currently, there are good options in most wheat classes for growers to select varieties with good to very good resistance to stripe rust. If stripe rust is present, protecting the flag leaf and penultimate leaf (the upper two leaves) and the upper part of the stem is important because those essentially provide nearly all of the green area needed to fill the head. So far, Kutcher’s results have found that early flowering is an effective fungicide time for wheat varieties with no stripe rust resistance.

Crop staging

For cereals, Dokken-Bouchard says to spray at flag-leaf emergence for leaf spots and rusts, as photosynthesis by the last two leaves on the plant contribute the most to yield. For Fusarium head blight (FHB), spray when the main head is 75 to 100 per cent emerged and no later than 50 per cent flowering. Wheat is susceptible to FHB during flowering. By the time you see FHB symptoms, it is too late to spray. Stripe rust can also spread to the glumes, so a fungicide application at FHB timing may provide added benefit if stripe rust is observed after the flag leaf stage.

Most pulse crop pathogens need moisture and green, living tissues to infect and spread. Generally, the recommendation is to spray during flowering to protect the crop yield; applying fungicides later in the season to protect new growth may delay crop maturity says Dokken-Bouchard.

“Applications after canopy closure are generally ineffective in controlling sclerotinia white mould and botrytis grey mould in lentils because these diseases develop in plant canopies too dense to allow penetration of a fungicide. Later fungicide applications can protect the developing seeds from infection so seed growers may benefit. However, once the crop starts to visibly ripen it will likely not make a difference,” she explains.

For sclerotinia in canola, the recommendation is to spray at 20 to 50 per cent bloom as the fungicide needs to cover the petals in order to protect against the disease. By the time you see symptoms of sclerotinia, it is too late to spray. The earlier the infection takes place, the greater the potential damage; therefore spray to protect the most blossoms at the earliest stage. Petals infected after 50 per cent bloom may still lead to disease, but the impact will be less intense as the petals are likely to drop into the upper canopy and later infections have less time for the disease to progress.

Other considerations

Fungicide application isn’t a black and white decision. Many other questions must be asked, says Dokken-Bouchard. Is disease present? Fungicides cannot cure disease. If effective control has not been achieved during the season and symptoms are already widespread, it is usually too late to apply a fungicide.

Has the crop been damaged by other factors? Are there other reasons it may not be worth saving? Do you expect the crop to recover? Crops often recover from damage such as hail if it occurs early in the season. However, if significant injury occurs during podding/seed development, crops are less likely worth saving.

Will flowers developing in mid to late summer have time to mature before fall frosts? For example, pulse crops require about one month to form mature seeds from flowers. Protecting late-season growth in August is rarely economical in regions where fall frosts are common in the first two weeks of September.

Weather conditions will also guide the spray decision, and are an important consideration in many fungicide decision support systems. Cool, wet weather will favour disease and potentially delay maturity. Warm, dry weather will naturally control diseases as well as help crops mature.

Will it pay?

While predicting crop yield response to fungicide application is difficult, it can help guide a spray decision. Ask what disease impact you are expecting and to what degree you anticipate that a fungicide will improve the crop yield/quality. A fungicide application is only warranted if it will make you enough money after harvest to pay for the application(s), and provide a return on both fungicide and application costs.

Expected Gross Return ($/acre) =

Estimated yield (unit/acre) X Estimated yield savings (%) X

Selling Price ($/unit)

Expected Net Return ($/acre)

Expected Gross Return ($/acre) minus Fungicide application costs (fungicide and application; $/acre)

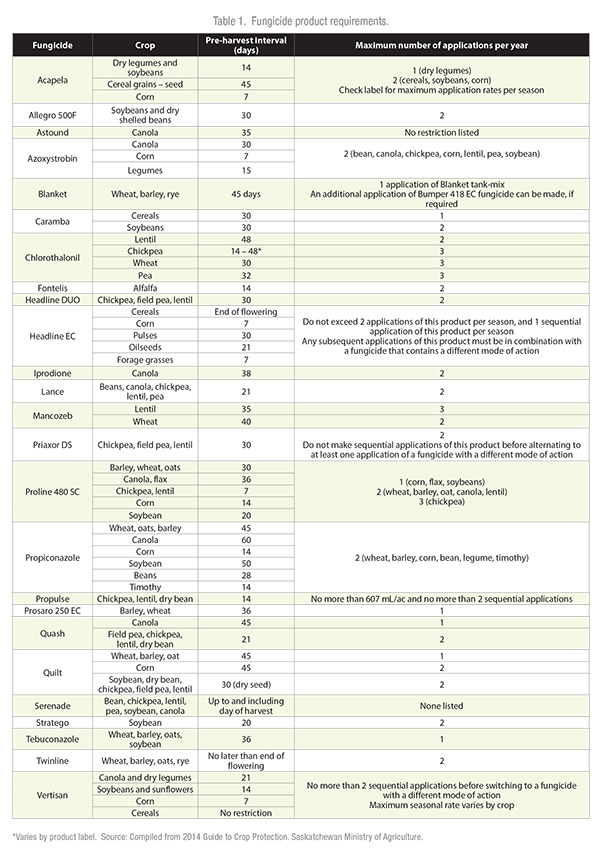

Check the label

Product label requirements are also important, as they guide scientifically proven and acceptable uses of the products, and govern maximum residue limits in seed, which also impact export standards. Fungicides have a maximum number of applications per year that can be applied to a crop, and established pre-harvest intervals (see Table 1). Also consider whether you are using a proper fungicide rotation to help manage fungicide insensitivity.

In the end, Dokken-Bouchard provides one final thought that will guide growers: “When deciding whether to stop spraying fungicides, keep the disease triangle in mind: the stage of the host crop; the potential of the pathogen to cause further damage and the environmental conditions expected for the remainder of the season.”

May 8, 2014 By Bruce Barker