Features

Agronomy

Weeds

Potential for new weed control technologies in Canada

Ongoing research in Western Canada is looking at alternate weed control technologies that do not utilize herbicides to target weeds.

June 20, 2016 By Breanne Tidemann PhD Candidate Department of Agricultural Food and Nutritional Science University of Alberta Edmonton Alta.

Wild oat was not a candidate for HWSC. Ongoing research in Western Canada is looking at alternate weed control technologies that do not utilize herbicides to target weeds.

Wild oat was not a candidate for HWSC. Ongoing research in Western Canada is looking at alternate weed control technologies that do not utilize herbicides to target weeds.Herbicides typically target annual weed species at the seedling stage. Harvest weed seed control (HWSC), an Australian paradigm of weed control, shifts the focus of weed control from the seedling stage to the adult stage, after the seeds have been formed and before they go back into the seedbank.

There are several requirements for weed species to be compatible with HWSC. Weed seeds must be retained on the plant at the time of harvest. The weed seeds must also be produced at a height from where they can be collected. If weed seeds are being produced at ground level, swathers or combines will not be able to collect them without being damaged.

Several research studies are being conducted in Western Canada. My research study was done to determine if height and seed retention requirements are met by wild oat, cleavers and volunteer canola. These weeds were chosen because they are numbers two, three and six in relative abundance in Alberta, and numbers two, nine and 14 on the Prairies. Cleavers is also the fastest increasing weed in terms of relative abundance.

The other reason these weeds were chosen is the increase in herbicide resistance, particularly in wild oat and cleavers. Hugh Beckie with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Saskatoon has identified wild oat and cleavers as two of the three next most likely weeds for developing resistance to glyphosate in Western Canada.

At the three study sites at Lacombe and St. Albert, Alta., and Scott, Sask., fababeans and wheat were seeded at 1x and 2x normal seeding rates, and were cross-seeded to wild oat, cleavers and volunteer canola. The two seeding rates will allow us to see what competition is doing to weed species retention. Shatter trays were placed underneath the canopy to catch lost weed seeds, and were checked two times per week until harvesting.

Harvesting was done at three different timings: wheat swath timing, wheat direct harvest and fababeans direct harvest. At harvest timings, the crop canopy was sectioned over four heights at 0-15 cm, 15-30 cm, 30-45 cm and 45+ cm, to determine where the weed seeds are produced in the canopy.

Below 15 cm is considered an un-harvestable fraction and weed seeds in this fraction would be considered lost to the seedbank. Across all height fractions, retained seeds were counted and the number of lost seeds and percentage of retained seeds were calculated.

Two field seasons have provided preliminary data. Height does not appear to be a limitation. The vast majority of wild oat and volunteer canola weed seeds were in the 45+ cm fraction high in the canopy. Cleavers were more widespread throughout the canopy, but concentrated in the 30+ cm fractions.

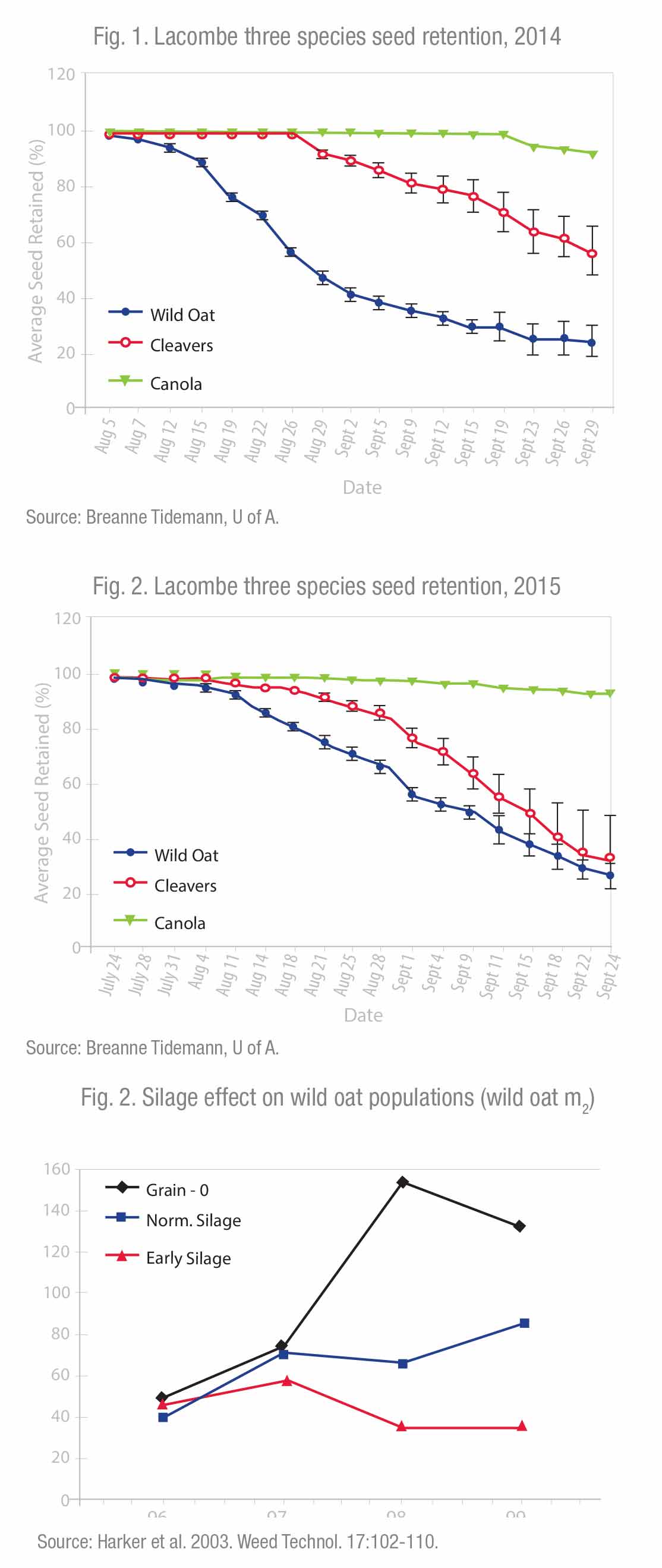

Weed seed retention was variable. Using Lacombe 2014 as an example, wild oat by the time of wheat swathing had less than 60 per cent of seed retained. By wheat harvest, wild oat retention was down to about 20 per cent.

Cleavers had full retention at time of swathing and then started to decline. Swathing may provide an opportunity to increase the cleaver seed available to target with HWSC at harvest. Volunteer canola had almost full retention through all harvest timings. (See Fig. 1.)

In 2015 at Lacombe, wild oat was retained better: about 70 per cent at wheat swathing, 60 per cent at direct harvest and 30 per cent retention at fababean harvest. Cleavers had a little less retention overall with higher losses at fababean harvest. Volunteer canola had very little loss at any point. (See Fig. 2.)

At the Scott and St. Albert sites, similar trends existed. Overall at all three sites, there was variability between sites, years and weed species. Generally, volunteer canola is very well retained, across sites and years, and looks like a good weed target for HWSC. Cleavers is variable and the crop may need swathing, but more research needs to be done to understand the variability of seed retention. Wild oat consistently loses seed early and doesn’t make a good target for HWSC.

Nikki Burton, a M.Sc. student at the University of Saskatchewan (U of S), is conducting additional seed retention studies. Her research is looking at similar studies in wheat and field pea, as well as seed retention in producer fields.

Combining my U of A research and the U of S results, the preliminary results suggest volunteer canola and green foxtail are excellent targets for HWSC. Cleavers and wild mustard may be good targets but may require swathing or the use of early maturing crops or some other method that allows early-season harvesting with good weed seed retention. Wild oats are poor targets.

Upcoming research in Western Canada in 2016 will look at the Harrington Seed Destructor purchased by AAFC. The trials will be done in a stationary format rather than pulled behind a combine. These include looking at questions such as: What about really small and really large seeds – kochia, wild buckwheat? What about the number of seeds – 10 seeds versus one million? How will the amount of chaff affect seed destruction – we have heavier crops than in Australia, so how will that volume affect the seeds? What about the type of crop and how will that affect performance?

Other technologies

Other technologies are being investigated. Research at AAFC Lacombe is looking at targeting wild oats as the seeds are being formed, rather than when mature. It is looking at whether seed formation can be prevented by cutting off the wild oat panicle when it appears above the crop canopy. We don’t know when those seeds become viable; if we cut them off above the canopy, are we preventing viable seeds from forming, or are we just putting viable seeds on the ground?

One small plot trial is cutting off the wild oat panicle and keeping it to assess for viability. An additional trial is cutting off the wild oat panicle and dropping it to the ground, seeding a crop the following spring, and assessing re-emerging wild oat populations. Weekly cuts from panicle emergence to seed shed are being assessed.

On a larger, commercial scale, silage is a way of cutting wild oat at panicle formation. Research by Neil Harker with AAFC at Lacombe has shown the benefit of early silaging in reducing wild oat populations. When barley was grown for grain with no herbicides, wild oat populations increased quickly over time. Normal silage timing with no herbicides helped to reduce populations of wild oats over four years of the study. Early cut barley, one week after crop heading, had wild oat populations decline to less than 10 plants per square metre.

In the trial, the early silage without herbicide treatment still had fewer wild oats per square metre than the treatment with a full rate of herbicide applied to barley grown for grain harvest. (See Fig. 3.)

Another new technology that may have potential is the Combcut, a Swedish machine. It is a selective weed “mower” used in cereal crops or above other crops. Stationary knives run through a cereal crop at an early enough stage that the cereals bend and are unharmed, while broadleaf weeds don’t bend and get cut off.

Another approach is to raise the Combcut above the crop canopy to cut off the seed heads of wild oats and possibly wild mustard or kochia seed. For farmers who do not silage, the Combcut may be a potential way to cut panicles and prevent seed formation.

Targeting seedbank weeds below the soil surface may be another possible weed control solution. A lot of research has been conducted over the years but this approach is still an elusive solution.

Other future technologies may include RNAi, precision tillage, vision guided tillage and autonomous weeders. Unfortunately, some of these technologies are 10, 15 or 20 years away from commercialization.

In the meantime, don’t forget the basics of establishing a competitive crop. Seeding rate is important. Of 91 cases in the literature in 29 different crops, only six failed to show decreasing weediness with increasing crop density. Use the 4Rs of fertilizer application. Pay attention to seeding depth, variety selection and crop rotation. Good agronomy makes your crop more competitive and helps take the advantage away from the weeds.

We have gotten into the cycle of using one herbicide and then when it doesn’t work, switching to use another herbicide. It just isn’t working anymore and we need to look at other alternatives.