Features

Agronomy

Weeds

Harvest weed seed control in Australia

The widespread evolution of multiple herbicide resistance in annual weeds infesting Australian cropping fields has dramatically depleted the available herbicide options and forced investigation into the development of alternative weed control strategies. One approach that is now widely adopted in Australian cropping systems is referred to as harvest weed seed control (HWSC), which targets weed seed during grain harvest to minimize seed inputs to the seedbank.

June 28, 2016 By Michael Walsh Associate Professor and Director of Weed Research University of Sydney Australia

Harrington Seed Destructor.

Harrington Seed Destructor. Harvest weed seed control came about because of an opportunity to target weed seeds during crop harvest. Farmers figured out quite quickly how to target weeds with HWSC. Their four main weed species were wild oats, wild radish, bromegrass and annual ryegrass. They all have very high seed retention at crop maturity.

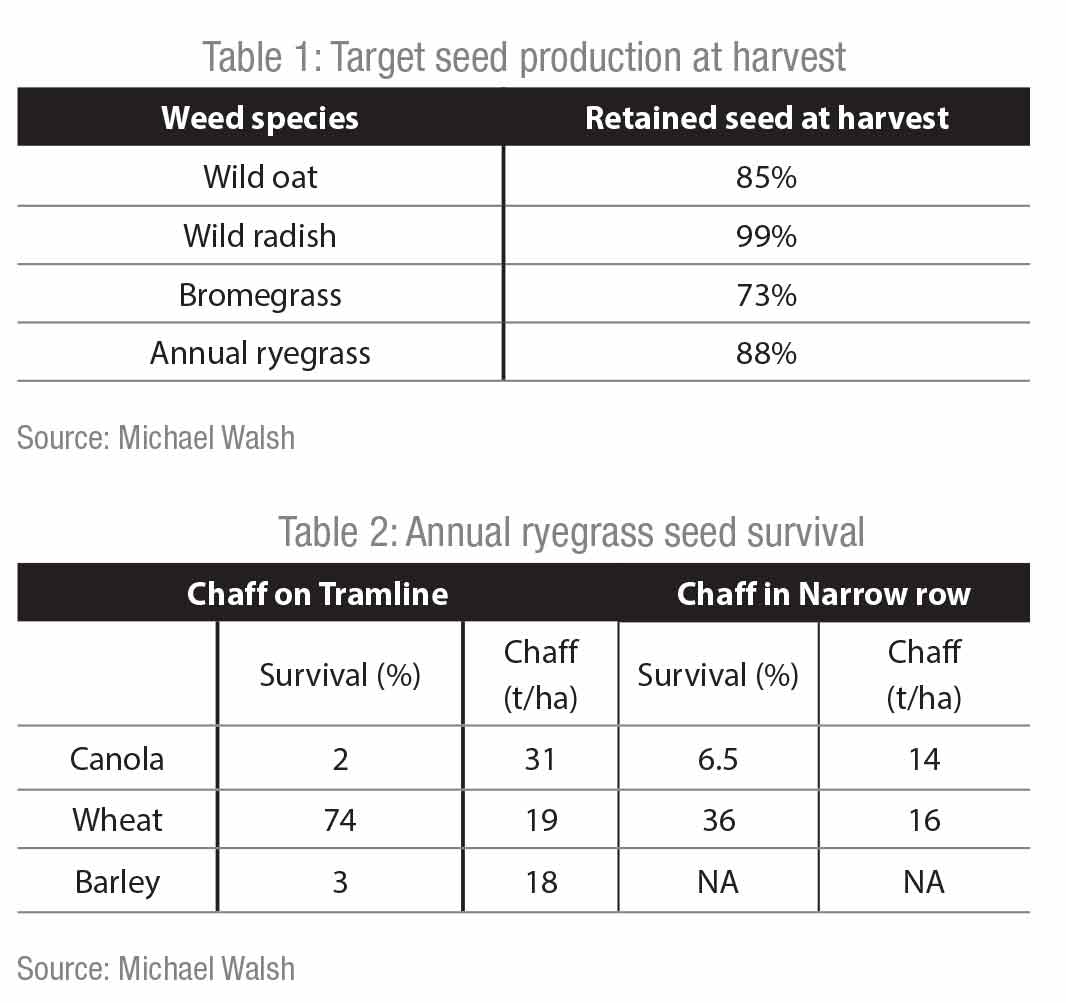

Seed retention is the proportion of total seed production retained at a height that can be collected during the harvest operation (see Table 1).

Seed retention changes over time. The proportion of weed seed retention declines the longer harvest is delayed past crop maturity. Wild radish and annual ryegrass have about one per cent decrease in seed retention per day over a 28-day period. Bromegrass and wild oats have a loss of seed retention of about two per cent per day. As a result, crop and weed maturity have an impact on the success of HWSC.

What used to happen at harvest in Australia was the combine spread the weed seeds back across the field, reseeding the weeds for next year. Growers in western Australia recognized they needed to interrupt that process and started to import chaff carts from Canada. They soon developed a love/hate relationship with chaff carts, which dragged on for about 20 years. Although the carts were effective they were frustratingly difficult to use.

Chaff carts collect the weed-seed-bearing chaff material, which is then left in piles around the field. The chaff piles are grazed by livestock or moved to feedlots, but with fewer sheep raised in Australia, the piles are typically burned to kill the weed seeds.

Ten years ago, a farmer, Lance Turner, modified the chaff cart by putting an elevator system on it to efficiently transfer the chaff out of the combine into the cart. The big impact was that the piles of chaff now burned out in two to four hours instead of up to two days. As a result, the adoption has increased and, in western Australia, at least 200 of these new chaff cart systems have been introduced since 2013.

One of the first users of the chaff cart system imported from Canada was the Shields family in western Australia. They subsequently developed a completely different system, called residue baling. During harvest, all residue goes into an attached baler. Farmers in locations where excess straw is an issue, and where there are markets for this material, can profit from the sale of baled residue. At the same time, weed seeds are removed – up to 95 per cent of annual ryegrass seed can be removed in baled harvest residue.

Another innovation in western Australia is the chaff lining system, which came about because not all growers like to burn residue. Burning means a loss of nutrients. Chaff lining systems collect chaff and drop it in the wheel tracks of a tramline system where there are dedicated wheel tracks in the field. Those wheel tracks are usually left unseeded and the weed seeds are left to break down in a hostile environment.

Another chaff lining approach is to catch and concentrate the chaff into a narrow strip. This chaff is concentrated in a row placed between narrow 17-centimetre row spacings where there is a mulch effect on the weed seeds.

Preliminary research measured survival of seed placed under chaff at harvest just prior to seeding the next year. Some of the findings were unexpected. Weed seeds didn’t typically survive under canola and barley chaff, perhaps because of some allelophathic effect. Interestingly in wheat, there was quite high survival of annual ryegrass seed underneath the wheat chaff, which is unexplained. More research is required, but overall, chaff lining works to reduce seed survival and is being rapidly adopted across Australia. (See Fig. 1.)

The next HWSC technology was chaff processing, developed by Ray Harrington 20 years ago. The technology uses a rotating mill to kill weed seeds. In research conducted with the Australian Herbicide Resistance Initiative (AHRI), it was found the technology provided greater than 90 per cent control of annual ryegrass through the mill across a range of speeds, and no effect of chaff type on weed seed destruction.

The first Harrington Seed Destructor was developed in 2006 as a pull-type unit attached to the combine where it collects and pulverizes the chaff and weed seed. The combine spreads straw separately. AHRI research found it worked just as well as the prototype, with seed destruction in the chaff at 95 per cent for annual ryegrass, 92 per cent for wild radish, 99 per cent for wild oats and 98 per cent for bromegrass.

The Harrington Seed Destructor (HSD) introduced a new way to control weeds in Australia. The cost of the pull-type machine is approximately $200,000 Cdn.

In 2010 and 2011, research was conducted comparing narrow windrow burning, chaff carts and the Harrington Seed Destructor at 25 replicated sites across Australia. It compared the three systems at the same sites at the same time with effects of these at harvest treatments assessed by measuring the impact on weed emergence. The overall result was that each technology reduced annual ryegrass emergence in the autumn prior to seeding by an average of 57 per cent. There was no difference between treatments at any of the sites. This makes sense because they are all targeting the chaff fraction, and if they are working properly, they should have the same result.

Recently, an integrated Harrington Seed Destructor (iHSD) has been developed that is incorporated into the combine harvester. It was launched into commercial production in March. This is a twin mill system. The previous pull-type HSD had counter rotating rotors. The iHSD has a fixed top plate and a spinning base plate. It is hydraulically driven and is powered by the combine harvester. De Bruin Engineering of Mount Gambier, South Australia, is manufacturing the iHSD (ihsd.com).

The iHSD works very well. Compared to previous research, it worked just as well or even better, with almost 100 per cent weed seed kill on the four weed species. This is a very exciting, new, non-chemical weed control system. The company is currently taking orders and is looking at building a small number in 2016, around 10 units. In the following year, they hope to go into full-scale production.

The most important HWSC message is the long-term impact on weed populations. Research by colleague Peter Newman, starting in 2001, looked at problem fields where annual ryegrass was out of control with plant populations of more than 100 plants per square metre. Twenty-five fields were monitored with 13 of the fields using herbicides alone; another 12 fields used herbicides plus a HWSC system.

After 12 years in the herbicide-only fields, annual ryegrass populations were reduced to about five plants per square metre and were stabilized at that level after six or seven years. Where herbicides plus HWSC were used there was even better control, with populations reduced to less than one plant per square metre.

When growers reduce annual ryegrass populations down to around one plant per square metre, managing weed populations to improve crop management/cropping is so much easier because the weeds don’t dictate how you manage the cropping system. Rotations can be changed. Herbicide applications can be dropped to take pressure off of herbicide selection. HWSC adds some insurance to your weed control program at harvest time.

Across the same 25 field sites, annual ryegrass seed set was estimated. The fields with five to 10 plants per square metre have about 1000 seeds going into the seedbank per square metre. The field with less than one plant per square metre has only a few seeds going into the seedbank. HWSC dramatically changes the whole weed control program.

A survey of 600 growers across Australia looked at HWSC adoption in 2013. Narrow windrow burning was adopted by 40 per cent of Australian crop producers. This practice is most widely adopted in western Australia, but is now becoming more common across all wheat growing areas.

One of the factors that has driven the adoption of narrow windrow burning and chaff lining is their low cost. It just requires a chute to concentrate the chaff and straw material; subsequent burning or mulching will potentially provide 95 per cent control of weed seeds. One of the lessons from the development of HWSC is the need for inexpensive but relatively effective alternatives that growers can use to evaluate the efficacy of these systems for themselves.

Low weed densities are the best insurance against herbicide resistance. The biggest driver against herbicide resistance is to have fewer weed seeds in your fields.