Features

Agronomy

Weeds

Harvest weed seed control

Presented by Breanne Tidemann, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Lacombe, Alta., at the Herbicide Resistance Summit, Feb 27-28, Saskatoon.

In order for harvest weed seed control (HWSC) to be effective, weed seeds still have to be retained on the plant at the time of harvest. If they’ve already dropped to the soil, they’re already in the seed bank. The weed seeds also need to be at a height where they can be collected by the combine. For example, chickweed is very low growing and its seeds are very low to the ground. Most producers don’t cut that low to the ground because of risk of damaging their equipment, so chickweed would not be a good candidate for harvest weed seed control.

Harvest weed seed control also means being able to get the weed into the combine. An example is a big tumbleweed, such as kochia. If the tumbleweed won’t feed into the combine and goes over top of the header, then you won’t be able to get the seeds into the combine for harvest weed seed control.

There are different methods of harvest weed seed control. Some of them have been scientifically evaluated in Australia. One of the most common methods is narrow windrow burning. The straw and chaff are dropped into windrows using metal chutes that are attached to the back of the combine. It’s cheap and easy to implement. But there are environmental impacts because it does involve burning. From a practical point of view, it may not work in western Canada, but it is used a lot in Australia.

Chaff carts were originally developed in Canada. The Australians have modified Canadian chaff carts and use a conveyer system instead of a blower system to move the chaff to the cart. They’ve also adopted new technologies to make burning or collection easier and more efficient. Some of the chaff carts are programmed with GPS to dump the chaff in a certain area of the field to be grazed or burnt.

There was one Australian producer that commented he’s been using a chaff cart for 15 years, and about 10 years in he started seeing annual ryegrass that was much shorter, much lower to the ground and was dropping its seeds much earlier. So this is still a selection pressure. You will select for resistance to these methods if it’s what you’re relying on to control your populations.

The bale direct system bales chaff and straw directly behind the combine into a square bale. The square bales are removed from the field, taking the weed seeds with them. The loss of the residue from the field can be detrimental in terms of nutrients loss. And there is potential for transport of weed seeds in the bale from one region to another, potentially moving herbicide resistant weeds with the bale. The other issue in Australia is one producer started doing this and he saturated the entire market. The bales can also be pelletized to produce pelletized sheep feed, but again it’s a relatively small market. So market can be an issue with this methodology.

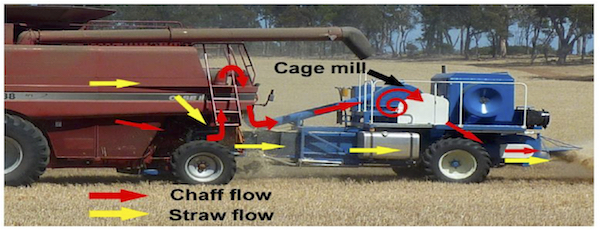

The Harrington Seed Destructor uses a cage mill to grind the chaff and weed seeds. The cage mill has two counter-rotating plates that spin very fast in the opposite directions. The weed seeds go in to the middle of the mill and have to move from the inside out to continue to move through the system. The straw moves along a conveyor belt and goes through a spreader at the back. Only the chaff is processed through the cage mill. The disadvantage is that the first model was towed behind the combine and required a lot of horsepower.

The tow-behind model was always intended as step one. The Integrated Harrington Seed Destructor (iHSD) is mounted on the combine and uses the same cage mill system. The integrated model had several improvements. Instead of having the two counter-rotating plates there’s only one rotating plate and one stationary plate, but that rotating one turns twice as fast. It is a hydraulically driven machine and takes about 80 horsepowers from the combine to run this machine.

A new combine mounted seed impact implement was first announced January 2017. The Seed Terminator is competition to the Harrington Seed Destructor. It uses a slightly different type of mill called a multi-stage hammer mill, but it works on essentially the same idea of crushing or grinding those seeds so that they’re dead and can’t grow the next year. This is mechanically driven rather than hydraulically driven. In terms of price differences, the original tow behind Harrington Seed Destructor was about $200,000. The integrated Harrington Seed Destructor is somewhere around $150,000. The Seed Terminator is about $100,000. So what you’re seeing is as these competitors come to the market that price point is dropping, and we do expect that to continue. Chaff deck or chaff tramlining works in a controlled traffic system. The idea is to put chaff on the permanent tramlines so if weeds grow there isn’t much impact on overall yield. The chaff in the tramline is also driven over multiple times, which can impair weed growth, and there is potential for seed decomposition in those tramlines. What farmers have seen is that there are fewer weeds growing in the tramlines, but it hasn’t been scientifically evaluated at this point.

Chaff deck or chaff tramlining works in a controlled traffic system. The idea is to put chaff on the permanent tramlines so if weeds grow there isn’t much impact on overall yield. The chaff in the tramline is also driven over multiple times, which can impair weed growth, and there is potential for seed decomposition in those tramlines. What farmers have seen is that there are fewer weeds growing in the tramlines, but it hasn’t been scientifically evaluated at this point.

Chaff lining can still be used outside of a controlled traffic system. The chaff is placed in a narrow row to decompose instead of spreading the seeds across the entire field. However, there is potential for some seeding or emergence issues if you’re seeding through this concentrated chaff row. It hasn’t been researched, but a lot of producers are adopting this in Australia as their first step in harvest weed seed control because it’s inexpensive and easy to implement.

The Australian experience

In Australia, a 2016 survey of 602 growers were asked about their adoption of narrow windrow burning, chaff carts, chaff tramlining, the bale direct, and the HSD. The Seed Terminator and integrated Harrington Seed Destructor were not released at the time so they don’t show up in the survey. Across Australia 43 per cent of producers were using some method of harvest weed seed control. Narrow windrow burning was the most common. In Western Australia that number goes up to about 63 per cent. Western Australia is essentially where all of these methods were developed. Western Australia is really the epicentre because of herbicide resistance, and harvest weed seed control is spreading out from there.

The adoption of chaff tramlining this past harvest has skyrocketed. There is a lot more discussion about different systems on social media, and a lot more discussion about what works and what doesn’t work than we’ve see in past years. If that survey was to be redone I think we would see some of the tramlining and chaff lining skyrocketing.

Results from the same survey show that 82 per cent of producers said they expected to adopt some form of harvest weed seed control in the next five years with 46 per cent expecting to use narrow windrow burning. More producers would like to be using the iHSD, but they had concerns about the cost and the perception that it was unproven in terms of weed kill. The perception of unproven control of weed seeds is interesting because weed kill is where there is the most research.

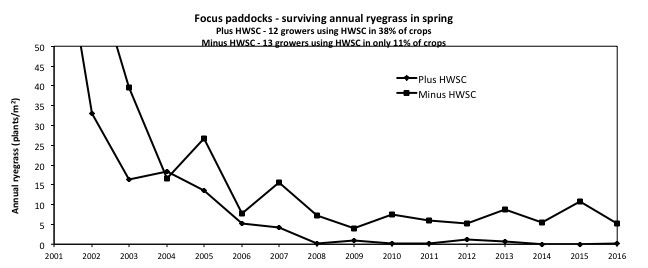

Research has been done in Australia to show how effective harvest weed seed control was on controlling annual ryegrass populations in “focus paddocks” or “focus fields.” The research compared crop rotations where harvest weed seed control was used in 38 per cent of crops compared to rotations where it was only used in 11 per cent of crops. The ryegrass population was managed far more effectively where harvest weed seed control was used, and it has stayed very low.

Effects of HWSC in Australia:

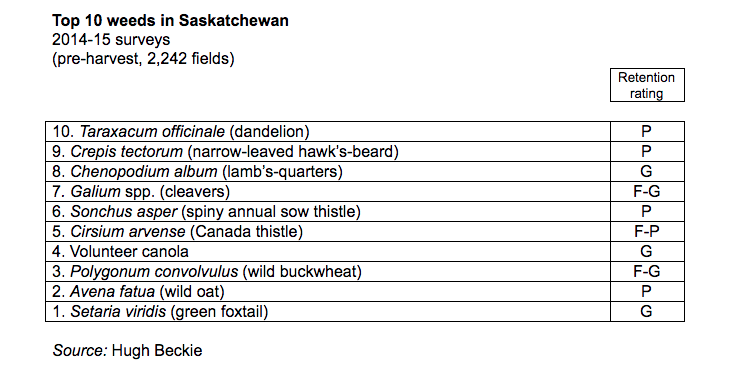

Potential in Canada

In Western Canada we’ve believed that the physical impact implements that destroy seeds are most likely to have the best fit. They don’t require the burning, and it has some scientific testing behind it that shows it’s effective. So that’s where researchers have focused efforts in terms of testing a method for Western Canada.We looked at the top 10 weeds in Saskatchewan and gave them a seed retention rating -- how well does the weed holds onto those seeds until harvest. A number of weeds are in the good or fair to good retention rating, and that’s promising. Green foxtail gets a good retention rating while buckwheat gets a fair to good. Volunteer canola is rated good. The unfortunate ones are the poors: wild oat, spiny annual sow thistle, narrow-leaved hawk’s-beard. Those have poor retention and are unlikely to be primary targets for harvest weed seed control because a lot of their seeds are already gone by harvest.

Looking at some small plot experiments, seed retention of wild oat, cleavers, and volunteer canola was looked at. Volunteer canola retained most of its seed by the end of September, cleavers was intermediate and wild oat retained about 20 per cent of the seed by the end of September.

Looking at some small plot experiments, seed retention of wild oat, cleavers, and volunteer canola was looked at. Volunteer canola retained most of its seed by the end of September, cleavers was intermediate and wild oat retained about 20 per cent of the seed by the end of September.Kochia has good seed retention. Their seeds only mature after harvest, so most of the seed is still there at harvest, but the concern is that below the cutting height, typically six inches, there can still be over 5,000 seeds below that cutting height. So even though a lot of seed is collected by the combine, there could still be a lot missed and left in the field. At this point we aren’t sure what impact harvest weed seed control would have on kochia.

As part of my PhD research, we looked at running samples through the Harrington Seed Destructor in a stationary format set up in the shop. We mixed buckets of chaff with weed seeds and ran them through to determine how many are destroyed. We looked at five weed seed species: kochia, green foxtail, cleavers, volunteer canola, and wild oat. We put 10,000 seeds of each of those species into a five-gallon pail of chaff, put it into the Seed Destructor and assessed how many lived when they came out the other side.

A second study looked at weed seed size. Weed seed species are all different shapes, sizes and seed coat types. We took canola seeds and we hand sieved them to get thousand kernel weights between 2.2 grams per 1,000 and 5.8 grams per thousand.

We also looked at weed seed number by comparing 10 canola seeds up to a million canola seeds in the same volume of chaff. We also looked at chaff volume, so 10,000 canola seeds going through with no chaff or up to eight five-gallon pails of chaff in the same timeframe. And we also looked at chaff type, so barley, canola, and peas.

When we looked at weed seed species we did find significant differences in terms of control but our lowest level of control was still over 97 per cent killed. It worked really well on all the species that we tested.

In terms of canola seed size, we expected to see an increase in control as the size of the canola seed went up, and we did. But again, we’re within a percentage point of 98.5 per cent control so weed seed size isn’t a big factor in control.

Looking at weed seed number, once you have over 100 seeds going through, we were back up at that 98 per cent control.

As we increased the amount of chaff going in, initially our control increased, which may be that there’s more deflection within that mill. Those seeds get hit an extra time or two, and then it started to taper off. But again, we are in the 98 to 99 per cent control so it’s not going to have a huge impact in the field.

There was a similar story with chaff type. We did have less control in our canola chaff but we were running volunteer canola seeds through the seed destructor so there was likely a background presence of volunteer canola in our canola chaff that we did not account for. But again it’s by one-half per cent and we are still getting 98 to 98.5 per cent control.

In summary, what we found with the seed destructor was if you can get the weed seeds into the seed destructor you’re going to kill most of them – greater than 95 per cent.

The big question now is how does it work in the field? The answer is we don’t know yet. We have an ongoing study with the seed destructor in 20 producer fields where the seed destructor is in the field at harvest time. We harvest with the seed destructor and compare it to a pass with the seed destructor not milling the chaff. We learned a lot of lessons in 2017.

The first is that air velocity is really key. Chaff needs to be moved from the sieves, up and into the input of the tow behind Harrington. In order to get the chaff from the sieves, it has to go up into an input tube, and takes a fair bit of air velocity. If your air velocity is too low, your machine will plug. And if you don’t catch the plug fast enough, you end up with burning belts.

Greener, wet material also doesn’t work. We know it takes a lot more effort for the combine to thresh green or wet material. It’s a similar story with the mills. You need higher air velocity, and without it the green, wet material can plug where it forms a nice solid block of really hot, wet chaff in the blower. Green, wet material doesn’t grind well, either. So if you have green material in the field desiccation or swathing is going to be needed to dry the material down.

The other complication the tow behind HSD is a big machine that has problems with hills. The integrated seed destructor or the Seed Terminator makes a lot more sense for Western Canada. The research that’s been done in Australia shows that the tow behind unit and the integrated unit are very similar in terms of their control, so it’s still a valid test for those integrated units in Western Canada.

An example from a single field in 2017 shows some interesting results, although very preliminary. We compared photos from an untreated and treated Seed Destructor pass. There was substantially less volunteer canola in the treated pass after harvest. There is still some volunteer canola, but there’s substantially less.

We hope to start seeing benefits in the spring of 2018, but it is a three-year study. We’ll be back on the same locations for the next two harvests so that we can take into account the seed bank buffering that we’ll see in terms of our treatments.

These are new strategies. There’s always going to be bugs to work out, but they can be very effective in helping us manage the herbicide resistance that we’re currently facing.

For more stories on this topic, check out Top Crop Manager's Focus On: Herbicide Resistance, the first in our digital edition series.

June 18, 2018 By Breanne Tidemann