Features

Weeds

Weed phenology can impact control

How weeds develop affect control options and timing.

October 27, 2022 By Bruce Barker

Weed phenology influences management practices such as clipping of wild oat.

Photo by Bruce Barker.

Weed phenology influences management practices such as clipping of wild oat.

Photo by Bruce Barker. How and when weeds grow can determine the success of weed management programs, and this weed phenology can change over time. The best advice is to catch weeds off-guard.

“There is an interaction between our management timing and weed ‘happening’ timing and how that affects the efficacy of management options,” says research scientist Breanne Tidemann with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada at Lacombe, Alta. “But perhaps a more intentional way of thinking about this is how to use weed phenology to your advantage.”

Weed phenology can be defined in different ways, but the basis of it are the various characteristics of the weed. These include emergence, emergence periodicity, synchrony with crop staging, days to flowering, flowering period, seed set, seed viability, and seed shed. Many of these characteristics can be tied to a specific time period, measured by standard calendar date, Julian date (days from the first of the year) and growing degree days.

Emergence and staging are some of the most important weed phenology characteristics when it comes to herbicidal weed control. Read any herbicide label and application timing is based on weed size or staging. If you want to control narrow-leaved hawk’s-beard in the spring with a low rate of 2,4-D, then you need to hit them at the one- to two-leaf stage – pretty small. But increase the rate by one-third and you can control it up to bolting. The staging and rate is important because trying to control narrow-leaved hawk’s beard at the one- to two-leaf stage is virtually impossible because 2,4-D application timing in wheat is at the four-leaf to early flag leaf stage – a time when the weed is long past two leaf stage so the higher rate would be necessary.

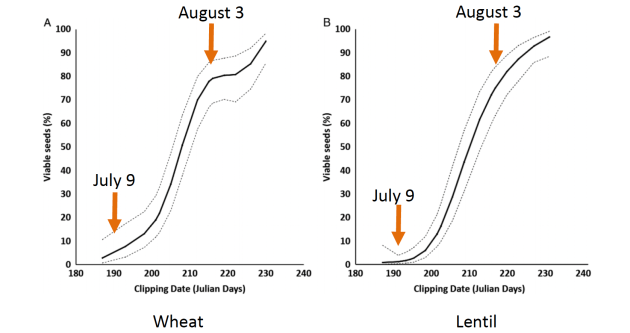

Another important factor in weed phenology is when seed viability develops. This can impact the success in preventing weed seeds from entering the seed bank. Research was conducted at Lacombe and Saskatoon in 2015 and 2016 to look at whether the clipping of wild oat panicles (seed heads) could be used to reduce the number of seeds entering the seedbank. Hand clipping of panicles was done weekly from panicle emergence to initiation of seed shed.

On July 9, about 10 per cent of wild oat seeds in the panicles were viable. By August 3, about 85 per cent were viable. The researchers found that clipping viable seeds wasn’t really preventing weed seeds from entering the seedbank.

Effect of clipping date on viable wild oat seed in wheat and lentil. Chart courtesy of Tidemann et al., 2016.

“Early clipping means longer exposure to insects, pathogens and the weather, but putting viable seeds on the ground isn’t helping,” Tidemann says.

When a weed produces seed is also an important factor in weed management. Research scientist Charles Geddes at AAFC Lethbridge is developing the new concept of the Critical Period of Weed Seed Control (CPWSC). The critical period for weed seed control (CPWSC) is the period of the growing season during which weed control can minimize weed seed production and return to the seedbank.

In Geddes’s research using kochia as an example weed species, he found that seed production could be decreased by up to 99 per cent through strategic timing of weed control when targeting the (four-day) window between 2,056 and 2,120 GDD starting around the third week of August. This approach using the CPWSC may help develop other management tools in addition to pre- or post-emergent weed control.

The CPWSC is different than the Critical Period of Weed Control (CPWC), which is when a weed needs to be controlled in-crop to prevent economic yield loss. For example, research at the University of Saskatchewan (U of S) found that lentils have a CPWC beginning at the five-node stage and continuing to the 10-node stage. The researchers stated that this is the period when weeds begin to start to accumulate significant growth and ends with lentil canopy closure.

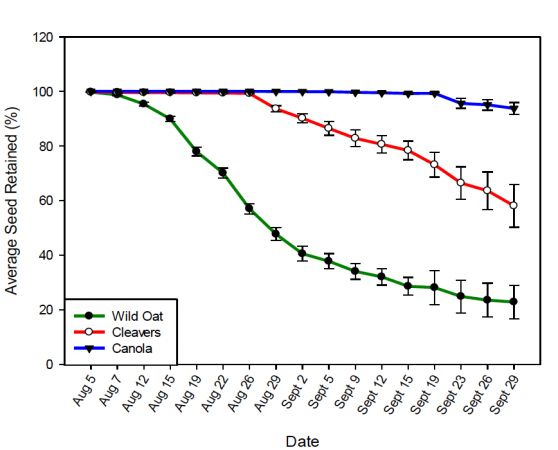

Weed phenology can also determine the success of Harvest Weed Seed Control (HWSC) practices such as using chaff carts to collect weed seeds at harvest, or a seed destructor to destroy weed seeds as they exit the combine sieve. The success of HWSC depends on when weeds shed their seeds.

Tidemann says the phenology of seed shed varies by weed species, environment, year and cropping system. In her research, she found that by Aug. 26, wild oats had shed approximately 50 per cent of seed, but cleavers and volunteer canola still retained almost all of their seed. By Sept. 29, this decreased to about 25 per cent average seed retention for wild oat, about 65 per cent for cleavers and 90 per cent for canola.

Retention of three weed species at Lacombe (2014). Chart courtesy of Breanne Tidemann.

“Differences in seed retention means differential levels of control by Harvest Weed Seed Control,” Tidemann says. “Only some weeds make good targets, because of their phenology.”

Management can affect phenology

Tidemann says that weed phenology can shift with management practices. The development of herbicide resistance is one example of selection pressure and how that can change weed phenology. The chosen herbicide and when it is applied can also affect weed phenology. An example comes from Andrew Kniss with the University of Wyoming. In his study in Nebraska, he found that kochia phenology changed. Applying isoxaflutole herbicide every year resulted in much higher kochia populations (113 plants/m2) after 12 years compared to glyphosate every year (3 plants/m2) or glyphosate/isoxaflutole in rotation (12 plants/m2). The reason is that isoxaflutole is a pre-plant, pre-emergence or early post-emergence herbicide, which meant that the kochia population, with a wide window of emergence, shifted to later emerging biotypes.

“We need to be aware of the pressure management puts on the weed phenology and how the phenology could change,” Tidemann says. “Keep an eye on what is happening in the field and make adjustments to management tactics.