Features

Cereals

Ultra-early seeding wheat

Seeding wheat at 2 C doesn’t compromise yield or quality.

September 27, 2020 By Bruce Barker

Ultra-early seeded wheat, at the very least, yields as well as conventional seeding dates, and often with a yield benefit. Photo by Top Crop Manager.

Ultra-early seeded wheat, at the very least, yields as well as conventional seeding dates, and often with a yield benefit. Photo by Top Crop Manager. When should wheat go in the ground? April 25? May 8? When the temperature hits 10 C? Chances are, most farmers go by a calendar date based on experience. Most studies and crop insurance guidelines refer to calendar date rather than soil temperature when it comes to seeding deadlines. But would you believe wheat seeded at soil temperatures of only 2 C could thrive?

“In recent years, there is an opportunity to get on the land earlier because of earlier and warmer springs,” says Brian Beres, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Lethbridge, Alta. “In our research, we identified the optimal seeding time as between 2 C and 6 C soil temperatures. So, rather than abide by an arbitrary calendar date, we developed an approach where a prescriptive soil temperature of 2 C is the ‘trigger’, if you will, to commence with planting wheat.”

A benefit of seeding earlier is that the crop has a better chance of avoiding the negative effects of warmer, drier summers on grain fill. It also helps mitigate the longer days to maturity for new, higher-yielding varieties. While Beres is quick to concede that this won’t work at every farm every single year, producers from a range of locations and latitudes have adopted the strategy and reports have all been positive.

Seed into soils between 2 C and 6 C

Beres led several research studies to determine the feasibility of seeding ultra-early into cold soils. The first experiment was conducted in Dawson Creek, B.C., Edmonton and Lethbridge, Alta., and Swift Current and Scott, Sask., from 2015 to 2018 to prove that ultra-early seeded wheat could work. Three experimental wheat lines with cold-tolerant traits were compared to AC Stettler. Wheat was sown when soil temperature in the top two inches (five centimetres) reached 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 or 10 C.

Ultra-early seeding resulted in no detrimental effect on grain yield. Grain protein content, kernel weight, and bulk density were not affected by ultra-early seeding, either.

“The sweet spot for optimal, stable yield was between two degrees and six degrees,” Beres says.

But what about spring frosts after seeding? Beres says a greater reduction in grain yield was observed from delaying planting until soils reached 10 C than from seeding into 0 C soils. This was despite extreme environmental conditions after initial seeding, including air temperatures as low as -10.2 C, and as many as 37 nights with air temperatures below freezing.

AC Stettler performed just as well as the cold-tolerant lines. Cold-tolerant wheat lines did not increase stability of the ultra-early wheat seeding system. “AC Stettler, and I suspect many of our CWRS varieties, have good tolerance to cold and frost given they were bred and selected in northern latitude environments,” Beres says.

Impact of agronomics

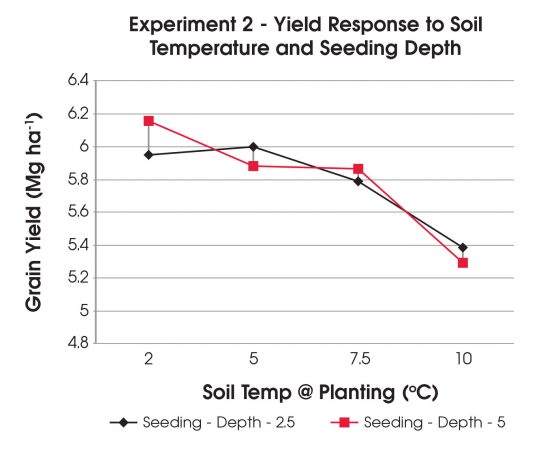

A second experiment looked at the interaction of several agronomic practices on ultra-early seeded wheat. Two cold-tolerant wheat lines were sown at 20 seeds per square foot (200 seeds per square metre) or 40 seeds/ft2 (400 seeds/m2). Seeding depth was one inch (2.5 cm) or two inches (5 cm). Soil temperatures at seeding were 0 to 2.5 C, 5 C, 7.5 C and 10 C.

In this experiment, Beres found that, generally, the optimum yield and stability was at 2 C, and the worst yield was at 10 C with lower seeding rates. The higher seeding rate had increased yield potential and stability, and occurred more frequently with a shallow seed depth.

Graham Collier, as part of his PhD research, is working with Beres on further refining recommendations for ultra-early seeded wheat. In one experiment, Collier is looking at the effectiveness of fall-applied pre-emergent herbicides.

“When you switch to ultra-early seeding, you lose the opportunity to apply a pre-seed burndown. There can be a benefit of increased crop competition with the crop emerging before or at the same time as weeds, but it does not replace the full value of a burndown application, and there is increased pressure on in-crop weed control,” Collier says.

Collier looked at fall-applied flumioxazin (Group 14; Valtera/Chateau) and pyroxasulfone (Group 15; various herbicides) alone or in combination with each other (Fierce herbicide). With the field research completed, he is finalizing the data analysis. His preliminary results indicate the residual herbicides provided good pre-emergent weed control the following spring.

Seeding ultra-early wheat on February 16, 2016. Photo courtesy of Brian Beres.

“I think we have found that there is a nice complementary action between the residual weed control and earlier presence of crop competition from ultra-early seeded wheat,” Collier says.

Collier was concerned that there might be some crop tolerance issues because seeding early into cold soils can result in slow crop growth, which slows herbicide metabolism. He didn’t see any tolerance issues. “I had horrible conditions one year. We had a really late snowfall after we had seeded, and cold, saturated soil, but we saw next to zero phototoxicity.”

Another experiment looked at nitrogen sources and application timing. Urea, ESN and SuperU were banded in the fall or spring. Ultra-early seeded wheat at 2 C was compared to conventional seeding at 8 C. Collier didn’t see any difference within nitrogen sources between soil temperature seeding treatments.

“The preliminary results are telling me that if you want to band most of your nitrogen fertilizer in the fall for ultra-early seeded wheat in order to reduce fill times in the spring, that it is okay instead of banding in the spring while seeding,” Collier says. “We didn’t see our wheat run out of nitrogen during grain fill because of losses from the system.”

Collier is also screening conventional wheat varieties to see if lines can be identified that perform equal or better in ultra-early seeding compared to conventional seeding. The results based on the presence or absence of certain genes could provide the basis for selected varieties predisposed to ultra early seeding.

Beres initiated another study in 2019 looking at the effects of opener configuration, seed treatment and soil temperature in an ultra-early seeded wheat crop. Unfortunately, he was unable to conduct the trial in 2020 because of AAFC’s COVID-19 policy restricting field research until May 26.

“The biggest message I have is that this is easy to do. There’s no additional expense to seeding ultra-early, and there is a demonstrable grain yield benefit,” Collier says.