Features

Agronomy

Soil

Too wet, too dry, just right

How fall rye cover crop options affect soil moisture and soybean yields.

February 28, 2022 By Carolyn King

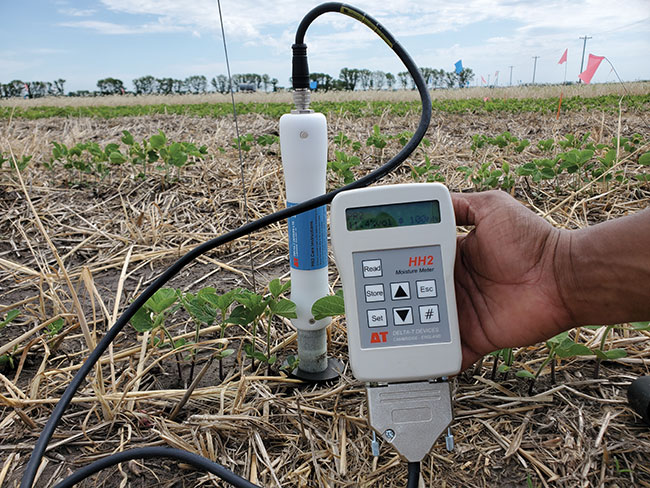

The University of Manitoba study tracked soil moisture levels in soybeans following different rye cover crop options. Photo courtesy of Chamara Imbulana Acharige, University of Manitoba.

The University of Manitoba study tracked soil moisture levels in soybeans following different rye cover crop options. Photo courtesy of Chamara Imbulana Acharige, University of Manitoba. I think cover crops are an interesting tool to deal with moisture extremes, either too much or too little,” says Yvonne Lawley, assistant professor of agronomy and cropping systems at the University of Manitoba. “It comes down to the kind of cover crop and the kind of management that you are going to use with that cover crop.”

She explains that cover crops can play a role in moisture management through both long-term and short-term effects. Over the long term, cover crops can increase a soil’s resiliency for managing extremes in moisture. For instance, by increasing soil organic matter and improving soil structure, cover crops can increase a soil’s water-holding capacity. As a result, the soil can absorb more water when precipitation is high and can store that water for later use if the weather turns dry.

In one of her current cover crop projects, Lawley and her graduate student Virginia Janzen are looking at short-term moisture management – how a cover crop could help a grower get through an immediate moisture crunch. They are working with overwintering fall rye as the cover crop and seeing how different termination options affect soil moisture levels and the growth and productivity of the following soybean crop.

“When we developed the proposal for this project, it was very much focused on extreme wetness because we had just come through a very wet time. Unbeknownst to us, we were transitioning into a very dry time,” Lawley notes.

“The project was intended to look at using overwintering cover crops to manage a well-known problem, which is excess moisture in the springtime. Could we use a cover crop to transpire water, moving at least some water out of the soil surface, to make conditions more favourable for planting or to improve trafficability by anchoring the soil?”

But a cover crop can also help deal with dry growing conditions, depending on how the cover crop is managed. For example, if you terminate a cover crop with herbicides, then the crop residues could reduce evaporation of soil moisture.

So, this project can shed some light on how rye cover crop termination options would work in either wet or dry scenarios under Manitoba conditions.

Funding for the project comes from the Manitoba Crop Alliance, Manitoba Canola Growers, and Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers, as well as the Ag Action Manitoba program of Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development. Also, funding support for the project’s soil moisture monitoring equipment and labour is layered on top of funding from the Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers for another study led by Lawley, which is about cover crops for low-residue crops like soybeans and edible beans.

Comparing rye termination options

The project took place at two Manitoba sites from 2019 to 2021. In all three years, one site was on a loam soil at the University’s research station near Carman. In 2019 and 2021, the other site was on a clay soil at Kelburn Farm, Richardson’s research farm just south of Winnipeg. However, because of the University’s pandemic-related research restrictions in early 2020, the clay soil experiment was moved. Janzen’s father, who farms near Morris, had a fall rye crop on a heavy clay soil. So, in a pandemic pivot, they did the experiment in his field that year.

The Carman and Kelburn sites had open-pollinated rye, while the Morris site had hybrid rye. The control plots had no rye cover crop.

Fall rye can make a good overwintering cover crop. For example, it is winter hardy, competitive with weeds, and easy to kill, and it builds organic matter and reduces soil erosion. In addition, a rye cover crop might offer more flexibility for a grower in the spring — if conditions are either too wet or too dry for soybean planting, then the grower could just let the rye continue to grow and harvest it.

Lawley chose soybeans as the cash crop in this project for several reasons. “Troubles with cover crops immobilizing nitrogen are less important with nitrogen-fixing crops like soybeans. In fact, nitrogen fixation can increase if you tie up some of the nitrogen,” she explains.

“Also, soybeans really need moisture in August, so there is the potential benefit, if you go from a wet period to dry weather, of having that cover crop residue reduce evaporation later in the summer. The rye residues might also reduce soil erosion from harvested soybean fields that typically we see when we have open winters in Manitoba.”

The project used herbicide-tolerant soybeans and terminated the rye using glyphosate.

In one set of treatments, the project team direct seeded the soybeans into the terminated or living rye cover crop using a planter capable of seeding through such residues. In the other set, the team strip tilled and then planted the soybeans into the same cover crop treatments.

Within each set of treatments, four termination timings were compared. The timings were relative to the mid-May soybean seeding date, a typical window for planting soybeans in Manitoba. The timings were: two weeks before soybean planting, which is a common recommendation for rye cover crop termination; a few days before planting; one day after planting; and two weeks after planting, which was to see how bad the soybean yield impacts might be if a grower couldn’t get in and terminate the rye any earlier.

The team generally did the strip till treatments around two weeks before soybean planting; at that stage, the rye was less than 3 or 4 inches tall.

They measured soil moisture in the soybean seed row, rye biomass, soybean stand establishment, soybean staging, and soybean yield.

Soil moisture findings

The growing season was fairly dry in each of the three years. Lawley summarizes, “In 2019, the growing season was dry, and then the fall was very wet, completely recharging the soil. So, in 2020 we started off with good soil moisture, but it was another dry growing season. Then in spring 2021, the tank was empty. We had a little rain in the spring, but otherwise it was dry, and our soybean crop was definitely drought stressed.”

As you would expect, the rye biomass increased from two weeks before soybean planting to two weeks after. She notes, “With the open-pollinated rye, rye biomass was still quite limited by the time we were terminating it in mid-May; it was under 1000 pounds per acre. With the hybrid rye, we had well over 1000 pounds per acre of rye biomass.”

In 2019 and 2020, the team had monitoring equipment to track soil moisture at 5 centimetres deep, a measure of planting depth moisture, and at 30 centimetres, a measure of rooting depth moisture. Then in 2021, they were able to purchase additional equipment for monitoring soil moisture in the whole profile down to a metre.

You might guess that the rye cover crop would increasingly dry out the soil profile as the termination date got later and later. Interestingly, that was not necessarily the case.

In 2019 and 2020 at the three sites growing open-pollinated rye, there were no moisture differences at 30 centimetres depth between any of the treatments, including the control treatment with no rye cover crop. At five centimetres, all the rye treatments caused some drying compared to the control treatment, but not extreme drying due to the moderate amount of rye cover crop growth. This surface drying indicates a rye cover crop could be helpful in a wet spring when growers are trying to get into their fields to seed.

The higher biomass hybrid rye plots at Morris in 2020 definitely used more moisture than the no rye control treatment, especially in the surface soil. Lawley notes, “So, depending on whether we’re talking about really wet or really dry conditions, the higher biomass production from a hybrid rye cover crop could be a great thing or a terrible thing.”

In 2021, in the surface soil at 10 cm, they again saw some drying with the various rye cover crop treatments as compared to the control treatment. They also saw some moisture differences between the cover crop treatments, but the differences between strip tilled versus the direct seeded treatments were greater under the very dry conditions that year. Soil moisture at 10 cm was drier in the strip till treatment compared to the direct seeded treatment where no tillage occurred and residue was left in place to reduce moisture loss.

“In the soybean rooting zone, from about 15 to 60 centimetres, we saw no differences from our treatments. To me that says, regardless of our treatments, the soybeans were doing a good job of drinking up all of the water present in that really dry year,” Lawley explains.

“However, we did see differences once we got down to 1 metre. At that depth, our rye treatments were slightly drier than our control treatment with no rye cover crop.”

Soybean growth and yields

“I was really surprised by how much flexibility we had in timing the termination of the rye cover crop. Compared to our no rye control treatment, we didn’t see differences in soybean yields, all the way from two weeks before planting right to one day after planting,” says Lawley.

She adds, “We did see yield reductions where we terminated two weeks after planting. Although no one would plan on not being able to terminate the rye by soybean planting time, it’s good to know what the yield penalty would be if termination was really delayed.”

Lawley had hypothesized that strip tilling would improve soybean growth because it would reduce competition between the rye and the soybeans, especially when the rye was terminated later. “However, under the dry conditions that occurred during this

project we saw good stand establishment with and without strip till. And we didn’t see delays in soybean staging or any differences in soybean yield.”

She thinks the fact that strip tillage didn’t make much difference is probably a positive factor for enabling rye cover crops to fit with current soybean production practices in Manitoba. “Strip tillage is intended for wider row spacings, but in Manitoba the most common row spacing for soybeans is narrower, more solid seeded,” Lawley explains.

“Also, one of the challenges with strip till on clay soils in Manitoba is that farmers are very reluctant to do any tillage in the spring for fear of smearing the soil. In that situation, you would need to set up the strip tillage in the fall. In loam soils, you could operationalize a decision to add strip tillage to a rye cover crop in the spring with less risk.”

Take-home lessons

Lawley and Janzen are currently finishing up the data analysis for the project. Lawley points to some key take-home messages for growers in the results so far.

“Our findings show that, from a soybean yield point of view, a rye cover crop is something that farmers could try as a strategy for managing very wet or even very dry conditions before soybeans,” she says.

“We had some drying of the surface soil with the open-pollinated rye, which could help with planting. And we had greater drying when we had more rye biomass with the hybrid rye at Morris. And yet we still managed to have no difference in soybean yield.

“It may be that soybean yields were sustained later into the growing season because the rye residues were helping to conserve moisture. So, it may not be as simple as: you dried out the soil in the spring and therefore yields are going to be lower in dry year.”

She adds, “I don’t think our results hold for all crops following a rye cover crop, but I think planting a nitrogen-fixing crop has some merit.”

Next research questions

For Lawley, the project’s results are raising some fascinating new questions.

“It’s really interesting to think about cover crops in terms of risk management on the Prairies,” she says. “For instance, how much cover crop is needed for our Prairie environments with extremes of moisture? With more cover crop growth, we would see greater long-term gains in our soil building goals like increasing soil carbon and improving soil structure. But if we’re balancing that with conserving moisture or using some but not too much moisture, then would thrifty amounts of cover crop biomass be more appropriate for Prairie environments?”

She would also like to find out more about fall and early spring soil moisture dynamics with cover crops. And she wonders what those dynamics would mean for choices in cover crop types and management.

Trafficability is another interest. “In addition to yield, the timeliness of planting is a really important economic variable for soybean production. One of the reasons why farmers are using overwintering cover crops in the Red River Valley, especially our neighbours to the south, is because it allows them to drive across their fields when these heavy clay soils are wet in the spring.”

Lawley emphasizes that the need for more information around using cover crops to manage extremes in moisture is not going away, especially since climate change will likely bring more

extreme events in the years ahead.