Features

Inoculants

Seed & Chemical

Timely advice on using inoculants

Understand the why, when and how, first.

November 23, 2007 By Ralph Pearce

Research from one university in the US suggests the use of inoculants in soybeans to be a sure-fire method of boosting yields and increasing profits. Following more than 10 years of field tests, Dr. Jim Beuerlein of Ohio State University concludes growers can raise yields an average of 1.9bu/ac through the use of inoculants. He also contends such an increase will produce ‘a profit of about 300 percent when beans are worth US$6.00 per bushel and the inoculation material costs $3.00 per acre’.

Research from one university in the US suggests the use of inoculants in soybeans to be a sure-fire method of boosting yields and increasing profits. Following more than 10 years of field tests, Dr. Jim Beuerlein of Ohio State University concludes growers can raise yields an average of 1.9bu/ac through the use of inoculants. He also contends such an increase will produce ‘a profit of about 300 percent when beans are worth US$6.00 per bushel and the inoculation material costs $3.00 per acre’.

Beuerlein’s work is well known by many in eastern Canada, including Horst Bohner and Dr. Dave Hume. Although the two agree that inoculating new soybean fields is necessary, they question the recent surge of acres being inoculated in Ohio that have previously grown soybeans: a reported jump from 200,000 acres in 2006 to nearly two million in 2007. Bohner is the first to note that while the Ohio State University test results are consistent, similar research in Michigan and other states does not yield as clear a result. “Michigan’s numbers are lower and more inconsistent, and Indiana’s numbers, as you read their work and talk to their people, they wouldn’t recommend using it every year on every soybean field,” says Bohner, the soybean specialist for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Research data from Iowa is neither consistent nor significant. “It really seems to be a regional thing with regional differences.”

Like a form of mimicry however, it follows a pattern where some growers inoculate and others follow their lead. If fewer growers are inoculating, then less seems to be done in the region. Bohner estimates that 35 percent of growers in Ontario inoculate their soybeans.

The biology involved

From a biological and symbiotic perspective, inoculation is important for soybean production. To produce a 50bu/ac crop, soybeans will remove 210lb/ac of nitrogen. In most Ontario trials, about two thirds of that is soil N and one third is atmospheric nitrogen fixed symbiotically by rhizobia in the soybean nodules. The symbiosis occurs between the soybean plant and the bacterial strain Bradyrhizobium japonicum.

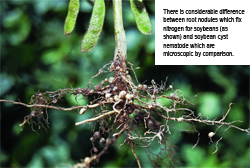

The bacteria help form the nodules which convert N2 from the air to more readily usable ammonium (NH4+). The soybean plant can convert the nitrogen it needs to grow while the rhizobia receive carbohydrates, minerals and a protected environment in which to live.

Bohner is involved in the first of a three year study to evaluate new inoculant technology in fields with a history of soybeans. He is reluctant to make recommendations based on just one year of data. “We’re reassessing the Ontario situation to see when it makes sense to inoculate. Is it soil

characteristics, growing conditions, or other factors that dictate when there is a yield boost?” he explains. “As a general statement, we already know that you’re more likely to have a response on low pH or sandy soils or if you haven’t had beans in that field for a number of years. And of course, if you haven’t had soybeans in a field before, you absolutely have to inoculate.”

The numbers involved

To Dr. Dave Hume, inoculating new soybean ground is a given. Yet he acknowledges all of the reasons why growers might not favour inoculating when soybeans have been grown previously, including the pay back, the apparent hassle of growers having to inoculate their own soybean seed and initially, the lack of visible results. “When those beans come up, they’re not going to have a whole lot more nodules on them, they’re not necessarily going to have a height difference or a colour difference,” says Hume, professor emeritus at the University of Guelph and a consultant with Agri-Trend Agrology.

The return on the initial investment when inoculating soils with a soybean history is like many agronomic practices: it looks better on paper when commodity prices are higher. Hume’s research has shown an average yield increase of 1.5bu/ac, but on a limited number of trials. At $9.00 per bushel, it is much more attractive than at $5.00. “The other thing that has changed is that you can get pre-inoculated soybean seed in the tote from the dealer and avoid all that hassle,” he says. “If it costs $6.00 to have the soybeans pre-inoculated and it has the potential of returning me 1.5bu/ac at $9.00 for $13.50, then that’s a pretty easy choice because there’s no hassle factor in there.”

In research done at Wheatley, Woodstock and Guelph, results have indicated that inoculants tend to remain in the soil once placed there. Hume had a graduate student load all the inoculant he could on soybeans, then tested whether the nodules were being formed by the bacteria in the inoculant or the bacteria that were in the soil. “The most we ever saw in any of those sites over two years was five percent nodule occupancy by the inoculant strain, rather than the strains already in the soil,” says Hume. “It’s really hard to move out the soil rhizobia population that is already adapted to that particular site and have an inoculant strain take over. Nobody’s figured out how to do this.”

Hume has seen some fields in tobacco sands lose their in-soil inoculants in very hot summers, but for the most part, it is very rare, he adds, to see a field where soybean rhizobia have disappeared. If soybeans are light green and appear N deficient, he says to check for nodules. “It’s easy for a farmer to detect areas in a field that have lost rhizobia, by inoculating one row on the drill or planter and not the others. If you can see the difference, you know you have a problem and you have to reintroduce inoculant into that soil,” says Hume. “So that’s easy to check.” n