Precision Ag

The Swinglet Cam

Technology is revolutionizing precision agriculture through the creation of exciting, innovative systems, and farmers have been quick to adopt these new technologies, particularly anything that reduces crop loss and maximizes returns. The Swinglet Cam is cutting-edge technology that takes precision agriculture to new heights, providing farmers with a tool that enables them to get a better idea of what’s going on in their fields.

June 10, 2013 By Melanie Epp

The drainage map is geo referenced. Technology is revolutionizing precision agriculture through the creation of exciting

The drainage map is geo referenced. Technology is revolutionizing precision agriculture through the creation of excitingAs a farmer of 20 years and a technical agrologist, Felix Weber knows that there are variations throughout his fields. For years, he’s been using technology to learn more about those variations, their causes and how best to manage them. In 1992, for example, he was one of the first to adopt yield monitor technology. Using the data he collected over four years, he created yield maps, comparing the differences he saw throughout his fields to data he already had, for example, soil samples.

“That told me a lot, but really it didn’t tell me the whole story,” Weber says. He believes that those lower-yielding areas aren’t something you have to accept; you just have to manage them differently. You can only do so, though, if you know what you’re managing for. Drainage is probably the best example, but there are many types of losses that farmers can experience that are likely very easy to correct. Until recently, though, technology hasn’t been sophisticated enough to allow for this type of micromanagement.

Enter the Swinglet Cam, created by SenseFly in Switzerland.

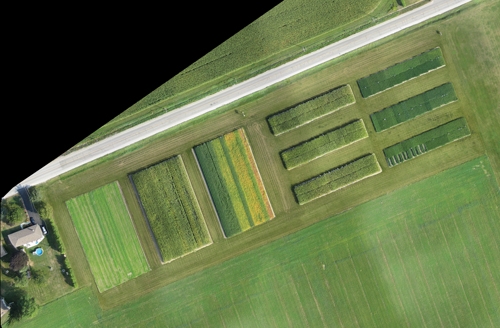

The Swinglet Cam is a flying camera that takes aerial digital images, which are later geo-referenced and stitched into 2D or 3D maps. The digital maps help farmers to locate trouble spots quickly, enabling them to act on pest problems or nutrient deficiencies better because you are able to see the good zones and stressed zones. As well it an easier process because you know where to look.

So how does it work?

Once released, the landing speed is about three metres per second but the climb speed and cruise speed is more. Although it has the ability to fly as high as 1,000 metres, in Canada, it can only be flown as high as 400 feet, and only with permission from Transport Canada. From above, the camera takes digital images of crops and in just 30 minutes, it can create images for up to 150 – 200 acres. At lower altitudes, the area covered is reduced, but resolution increases. Images are stored on an SD card; once the unit lands, the images are easily transferred to a computer where the software orthomosaiced it together, creating profile maps.

The camera itself sits in a hard Styrofoam shell that weighs about 500 grams and has a wingspan of 80 centimetres. The device is sophisticated enough to take off and land on its own, returning to within 20 metres of its original takeoff position. Operating in winds of up to 25 km/h, its light weight means that it can land on its own without any damage.

Weber uses two different cameras on his plane. He uses a “normal camera” – a Canon Ixus 12 megapixel camera – and an NIR (Near Infra Red) camera. In the near future, he hopes to use an upgraded 16-megapixel camera. Weber shows a preference for the NIR camera because the images it produces reveal potential problems before they even occur, but both types of cameras work quite well.

In the past, Weber says, he used satellite imagery on his farm, but felt that it just wasn’t good enough. He didn’t like having to depend on someone else to collect the data, a process that is highly dependent on weather conditions. If, for example, there is cloud coverage, satellite images cannot be collected. On top of that, Weber didn’t like that he had no control over timing and felt that as a result response times were too slow, sometimes as long as two weeks.

“Within that time period, the weather changed,” he says. “Whatever I saw on the satellite image was not reflected when I walked the field after, so to me that was useless.” The response time using the Swinglet Cam, however, is very short. Depending on the quality you want, it can be as short as an hour or as long as a day. “Because my response time is so short, I may be able to do a treatment right off the bat,” says Weber.

Although the Swinglet Cam wasn’t created with the agricultural industry in mind, it has become an invaluable tool to farmers like Weber. Its ideal users are farmers with over 1,000 acres or farm consultants who may want to support field walks.

Often, he says, the Swinglet Cam will pick up on a problem before farmers do on foot. “By the time the crop shows us there’s a problem,” he says, “That crop is sick. That crop is stressed.” If there is a fungus stress in the crop, for example, by the time you see if with your eyes, it’s probably quite advanced. Fungicides can’t reverse the process, but knowing there’s a problem earlier can help to avoid it altogether.

At a starting cost of less than $13,000, the Swinglet Cam can pay for itself, especially on larger operations. Weber knows a farmer who’s flying over his fields every two weeks to look for changes in his crops. Weber himself uses it to see patterns. The Swinglet Cam can be used to scout fields for variances from the air, to reveal bare soil differences, and to look for drainage problems. It can also be used to improve things like your spring nitrogen application. While Weber’s focus is mainly on looking for stress in a growing crop, others could use the Swinglet Cam to make better management decisions that could save money in the long run.

“I could see this being used as a tool to calculate crop loss due to spray drift,” says Weber. It can help to determine the right time for doing an application, and to decide whether or not the crop is worth keeping.

“From the ground it looks different than it does from the air,” says Weber. From the air, he can see what percentage of the crop is good, and what percentage is not so good.

As with all new technology, only time will tell how it will be used. For now, Weber says, its uses are endless. “We’re really barely scratching the surface of what this can do,” he says, “As every new tool comes out, we have to learn how to use it – find out what’s useful, and what’s not going to work.”