Features

Agronomy

Other Crops

The multiple personalities of barnyard grass

Barnyard grass is a major grass weed in eastern areas of the Prairies, and weed surveys indicate it is on the rise and spreading throughout the region. Weed scientists say there is much to learn about the weed, including proper identification because there is more than one species of barnyard grass, a native and introduced species.

March 1, 2010 By Bruce Barker

|

|

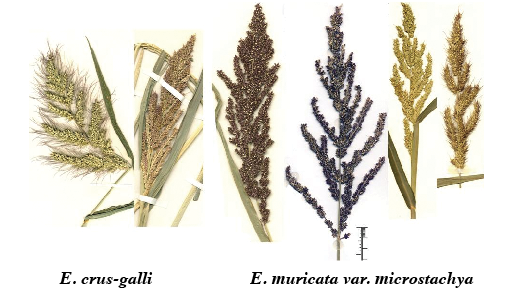

| Both species exhibit considerable morphological variation.

|

Barnyard grass is a major grass weed in eastern areas of the Prairies, and weed surveys indicate it is on the rise and spreading throughout the region. Weed scientists say there is much to learn about the weed, including proper identification because there is more than one species of barnyard grass, a native and introduced species. “The correct common name for the introduced species is ‘Barnyard grass’, while the correct common name for the native species is ‘Western barnyard grass’,” says Julia Leeson, a biologist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Saskatoon Research Centre. “However, in the past, few people have distinguished between the two species and generally assumed that the species present was the introduced weed.”

Leeson works on the Prairie Weed Surveys conducted by AAFC. She points out that barnyard grass describes the introduced European species Echinochloa crus-galli(L.) P. Beauv. Western barnyard grass is the native Echinochloa muricata var. microstachya Wiegand species.

The taxonomy and identification of the grasses have been difficult and controversial, and little is know about whether they react differently to agronomic practices. Barnyard grass (as a species complex, both native and introduced, combined) was ranked 35th in the 1980s on the Prairies, 25th in the 1990s and 15th in the 2000s based on Prairie Weed Surveys.

Recently, Gordon Thomas, a scientist at AAFC Saskatoon Research Centre, and Leeson initiated a study looking at the two barnyard grass species in order to better understand the identifying characteristics of the two species, and compare their distribution across the Prairies. Their collaborator Stephen Darbyshire, a taxonomist with AAFC in Ottawa, examined more than 190 specimens dating from 1906 to 2005, while Leeson and Thomas collected and examined 98 specimens from 2006 through 2008.

Both species were found in all three Prairie provinces, but the introduced E. crus-galli was less frequent. Both species were sometimes found at the same site. The introduced species was found more often in cultivated fields and disturbed areas in the recent collections. All specimens from native habitats were the native E. muricata var. microstachya.

Identification

In Canada, Leeson says the echinochloa species are relatively easy to distinguish from other grass weeds at the seedling stage by the absence of the ligule, a thin outgrowth at the junction of the leaf and stem. The plants have erect to horizontal stems up to 1.5 metres long. They are prolific seed producers with up to 750,000 to one million seeds per plant. The seeds are about 2.5 millimetres long.

Where things get difficult is distinguishing between the barnyard grass species. Leeson says the two can best be distinguished by examining the fertile lemma and palea in a spikelet in the panicle of a mature plant. However, these critical characteristics are small and best viewed at a magnification of 20 to 40 times on fully mature spikelets.

For example, on the native E. muricata var. microstachya, the top of the lemma gradually and smoothly tapers into a pointed tip, without a sharp contrast in texture, colour or pubescence. On E. crus-galli, the top of the lemma is broadly rounded with an irregular row of hairs. The short acute tip is abruptly different in colour and texture from the body of the lemma.

On a seed that is only 2.5 millimetres long, to the casual observer these characteristics are likely to be indistinguishable, so identification is best left to the taxonomy experts.

What is important moving forward, though, is that weed scientists need to better understand how the two species react to different agronomic management systems. For example, barnyard grass is controlled by many grass weed herbicides, but Leeson says that research has not been conducted to determine if the two species will respond the same to herbicide control. “We do know that while the two species are similar in appearance, they do not behave the same. For example, the introduced species come into head about a week earlier than the native species,” she explains.

In the meantime, it is known that cultivation will control barnyard grass, perhaps providing a clue to the increasing relative abundance in the presence of increasing no-till on the Prairies.