Features

Desiccants

Seed & Chemical

The Iowa pest resistance experience

As Dr. Mike Owen, longtime professor and weed scientist at Iowa State University, sees it, Iowa is a desert of corn and soybean. Iowa has approximately 14 million acres of corn and 10 million acres of soybeans. The two crops represent about 70 per cent of the landmass in the state of Iowa. And often, corn is grown back-to-back as growers chase the highest economic return.

“The problem that we have is that we are truly lacking in diversity. Consider that this type of non-diverse environment over such a large scale has overriding implications on pretty much everything,” says Owen, who spoke at the Manitoba Agronomist Conference at Winnipeg, Man. in December 2013. “I dare say it is inevitable unless you are smart about the changes that you make.”

Owen says the changes to production agriculture in Iowa are driven not so much by agronomics, but by economics and sociological changes. The political discussion around ethanol has driven the growth of corn production and revenues, skewing rotations away from diversity and impacting agronomic decisions made by growers and professionals.

“Even when looking at soybean prices of $14 to $15 per acre, we were still making more money growing continuous corn, which gets us further down the bad trail with regard to diversity and pest management,” he says.

In Western Canada, there is currently a more diverse rotation than Iowa’s rotation of Roundup Ready corn and soybean or continuous corn. However, rotations have begun to tighten up in Western Canada, with wheat and canola (approximately 50 per cent Roundup Ready canola) the most common rotation, and in some instances, continuous canola. That diversity is also changing with the increasing Roundup Ready soybean acreage in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, and an increased breeding focus on short season Roundup Ready corn for Western Canada.

“Predictably, because of this lack of diversity, pests – not just weeds, but pests – are evolving resistance to the strategies that growers are willing to use to manage them,” says Owen. “Interestingly, [farmers in Iowa,] Manitoba, Canada, Honduras, the thought process is very much the same. We are doing stuff because of the tools that are available; we’re creating the problems that we have.”

In Iowa, Owen says weeds are the most consistent problem, more than any other pest complex, because they are always there and farmers are always trying to control them. Waterhemp, an amaranth species, has populations with resistance to five different herbicide groups including Group 9 glyphosate. Horseweed/marestail and giant ragweed have also evolved resistance to Group 2 and 9 herbicides.

The corn rootworm complex is starting to evolve resistance because one of the management strategies for the rootworm complex was rotation between corn and soybean. Now with continuous corn and the use of Bt and multiple Bt genes, the selection pressure is causing an evolution in resistance. Owen says growers are now going back to the “good old days” of soil-applied insecticides because of evolved resistance to Bt.

“It comes as no surprise to me that the phenology of the rootworm is pretty much similar to the phenology of weeds, which is not terribly different to the phenology of the cyst nematode. It kind of stays in one place, moves around a little bit, but the selection pressure is similar. So we’re beginning to see the system, as it moves to less diverse, simpler, more convenient approaches, the system is pushing back.”

The evolution of weed control

Like Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory, where selection pressure initiates changes in species, the same concepts of selection and evolution of the pest complex in agriculture is occurring, but at warp speed. Owen says from the early 1900s through to today, agricultural practices in Iowa have eliminated most of the cultural and mechanical pest control practices. He says at one time, crop rotations, herbicide rotations, tillage, row spacing and planting dates helped with weed control. Now, at least in Iowa’s case, growers rely primarily on one herbicide, glyphosate, for weed control. Since the introduction of Roundup Ready crops in the U.S. in 1996, the market share of glyphosate resistant soybeans, corn, cotton and sugar beets is all over 90 per cent.

“We have almost eliminated diversity in our crop production system,” says Owen. “This is not to say that glyphosate isn’t a good herbicide. This is not to imply that the technology is not good. But like any other tool, the technology has to be used in a manner that is sustainable.”

Owen says the shift to the reliance on only herbicide for weed control comes down to economics and time management. Drivers of this change are increasing farm size where owners and agronomists have less time to manage a diverse cropping system. He says the average land price in Story County in central Iowa went up 15 per cent in 2012 and five per cent in 2013 and sat at $9,000 per acre. Further north and west it is $12,000 to $15,000 per acre. Large farms are on the increase and mid-sized farms are being eliminated.

“The ones with large areas don’t have time to manage anything. They make more money managing the grain crop and marketing of the crop than making the technical decisions on how to grow a crop. They are looking for simplicity and convenience. The siren song of those two are driving the system where they don’t have the time to do things correctly,” says Owen.

In Iowa, glyphosate is used on almost 100 per cent of all soybean acres and 90 per cent of corn acres. There is a bit of a recent increase in other herbicide use in soybean and corn, but in Iowa, out of 24 million acres, an estimated nine million acres have only glyphosate applied. Glyphosate is the primary if not sole selective factor for weed resistance.

Owen says the system is, predictably, pushing back. There aren’t a lot of train wrecks, but resistant patches are showing up in many fields. “We did a random survey of 400 fields in Iowa last year, and what we found was that 70 per cent of soybean fields had weeds above the canopy. You see that in August and September and something bad happened.”

Once a herbicide-resistant population is noticed by growers, it has become large. Research has shown that before herbicide resistance is noticed in a field, approximately 30 per cent of a weed population has evolved resistance.

“So you’ve gone through a number of reproductive cycles, and now the seed bank is full of resistant individuals. Once it goes from additive to logarithmic, the change will happen incredibly fast,” cautions Owen.

A 2011 study of 400 samples of waterhemp populations shows the worst-case scenario for Iowa growers (the samples weren’t randomly selected). Sponsored by the Iowa Soybean Association, the study found waterhemp was resistant to five different herbicide groups. Around 96 per cent were resistant to Group 2 (ALS inhibitors), just under 60 per cent to Group 5 (triazine), around 55 per cent to Group 9 (glyphosate), just under 10 per cent for Group 14 (PPO inhibitors) and 25 per cent demonstrating resistance to Group 27 (bleaching).

Each population was also screened with all five herbicides. Owen says, not surprisingly, that one third of the populations were resistant to all three of the following herbicides: Group 2 (ALS herbicides from the heyday of the 80s and 90s); Group 5 (atrazine, still the second most widely used herbicide); and Group 9 (glyphosate, the most widely used herbicide). And about five per cent of populations were resistant to all five herbicide groups.

“If you are a grower, or helping your grower, trying to come up with a management program that is convenient and simple and economic, it is getting increasingly more difficult. Right now in Iowa, 88 per cent of waterhemp has multiple herbicide resistance,” says Owen. “We got there because of the decisions that were made without an overriding understanding of the repercussions of the decisions.”

Glyphosate resistant giant ragweed has also become a problem in Iowa, and has been identified in Ontario. In the Mississippi delta in southeast U.S., glyphosate resistance is a problem in Palmer amaranth, which has moved up into Iowa in contaminated feed. It is a desert plant, but has adapted to the Midwest U.S. and could adapt further north.

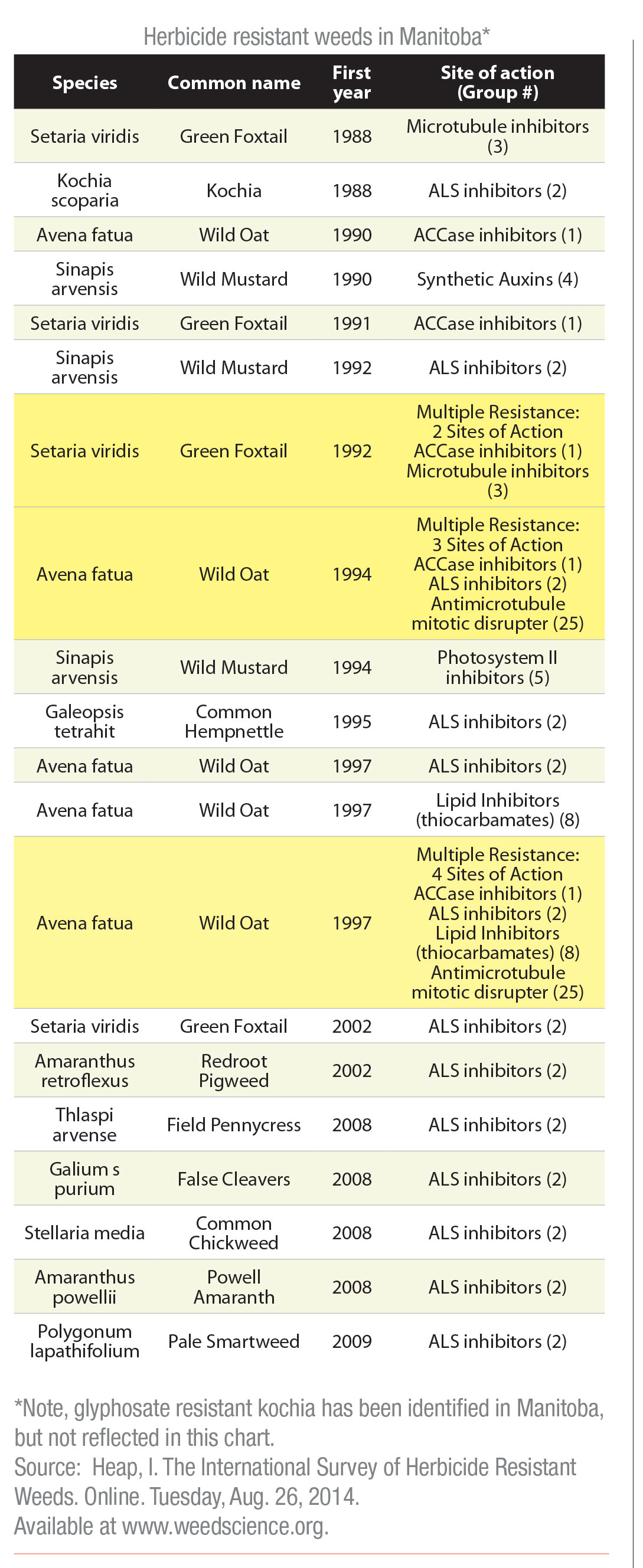

In Manitoba, 11 weed species have been identified with herbicide resistance. Most of the broadleaf weeds are resistant to Group 2 ALS inhibitors, but wild mustard has also shown resistance to Group 4 Synthetic Auxins and Group 5 triazines. Additionally, a 2013 survey of 283 different kochia populations in Manitoba found two populations resistant to glyphosate.

“I see a lot of Group 2 resistance [in Manitoba], but I am more interested in the specific weeds that might adapt well to corn and soybean production. Green foxtail; kochia, which is becoming a poster child in the west for herbicide resistance; Palmer amaranth; redroot pigweed. My point is that you are already part way there. You just need to shift things a little bit more the wrong way and you’ll end up in a bad situation unless appropriate management is applied,” cautions Owen.

Management recommendations

Owen starts with scouting as a foundation for weed control. Especially in Iowa where fields have many different resistant populations, scouting helps identify what effective herbicides are left for a particular field.

On all acres across all crops, weed specialists are promoting an effective pre-emergent treatment with multiple modes of action. He cautions that multiple modes must be effective on the weed biotypes in the field. In Iowa, many herbicide products contain a Group 2, but many weed populations have Group 2 resistance so growers must make sure their herbicides include additional modes of action that are effective. The direct parallel in Western Canada is kochia, where weed scientists assume all populations to be resistant to Group 2 herbicides, and other Groups should be included in a pre-seed burndown with glyphosate to help manage herbicide resistance.

Effective and timely post emergent herbicide applications seem like a given, but Owen cautions that growers need to target herbicides to protect yield, not control weeds. Otherwise, they are unnecessarily putting selective pressure on weeds.

“We have lost untold money by effectively killing a lot of weeds with glyphosate. We kill a lot of weeds in Iowa with glyphosate, but [not until] after they have competed with the crop and we have lost significant yield potential never to be gained.”

A diverse crop production system is key to controlling weeds and prolonging effective herbicide life. Owen sees problems on the horizon for western Canadian growers who are growing Roundup Ready corn and soybean in tight rotations.

“You need to start thinking about weed control and weed management, not just for this year, but you need to start thinking about what you are going to do three or four years down the road, and have a plan, and have a what if it doesn’t work, what will I do, what will it cost? You need to have that kind of plan to maintain that diversity,” he says.

Inevitably, without diversity, herbicides will fail. Weeds can even adapt to tillage. Waterhemp avoids cultivation by delaying germination.

In Iowa, Owen would like to see a more balanced approach to weed control that includes cultural, mechanical and herbicidal weed control tactics. He believes herbicides will remain an important tool in the foreseeable future, but they need to be supported by other control methods.

“And that’s a problem, because for growers in Iowa, we are so large, and so accustomed to simplicity and convenience that they can’t remember the way it was,” says Owen. “In fact, we have a whole generation, referred to as ‘Roundup Babies,’ who have never sprayed a herbicide other than glyphosate. They don’t know another herbicide exists.”

Owen recognizes that adding diversity isn’t easy for growers in this era of large farms and the drive for simple, convenient and profitable farming systems. He is working with rural sociologists and agricultural economists trying to figure out what kind of changes growers can make and still be profitable.

“Basically what I am suggesting is you need diversity, and if you choose not to have a more diverse system, then understand the inevitability of the failure with regards to weeds adapting. That will happen.”

November 6, 2014 By Bruce Barker

As more soybean and corn is grown in Western Canada As Dr. Mike Owen

As more soybean and corn is grown in Western Canada As Dr. Mike Owen