Features

Agronomy

Insect Pests

Target correct timing for optimum wheat midge control

In recent years, wheat midge Sitodiplosis mosellana moved westward into areas of Alberta that traditionally did not experience infestations previously.

October 20, 2009 By Bruce Barker

In recent years, wheat midge Sitodiplosis mosellana moved westward into areas of Alberta that traditionally did not experience infestations previously. While many fields did reach economic levels, and farmers and agronomists assessed and responded appropriately with insecticides, some fields were sprayed prematurely or at stages too late to justify. “There was some confusion in 2008 on proper management of wheat midge, but at least producers and agronomists were out looking for the insect,” explains Scott Meers, insect management specialist with Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development at Brooks, Alberta. “There was some spraying and some denial, and a fair amount of revenge spraying, late treatments. As an industry, that needs to be addressed because spraying at the wrong time or when it is not economic can hurt beneficial insects.”

|

|

| Wheat midge control requires proper insecticide timing. Photo courtesy of AAFC-Saskatoon Research Centre. |

In Saskatchewan and Alberta, the wheat midge forecast maps indicate that a reduction in risk is predicted for 2009. However, the forecasts note that there exists enough wheat midge across widely separated areas that individual fields across the Prairies could still be at risk. As a result, Meers recommends that farmers should still monitor fields at susceptible stages to ensure that wheat midge is not present at economic levels.

Wheat midge scouting review

Wheat midge overwinter as larval cocoons and may remain dormant until conditions become favourable. Research at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), Saskatoon has found that 20 millimetres of precipitation is required in April and May for wheat midge to continue development into the pupal stage. If this criterion is not met the result will be a delayed and extended emergence of the wheat midge adult. This may explain why in 2008, areas of eastern Saskatchewan with little precipitation in April and May experienced delayed emergence of the wheat midge.

Scott Hartley, provincial insect specialist with the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture (SA) says that farmers should understand the lifecycle of the wheat midge to better time scouting and insecticide applications.

Adults usually emerge from the pupal stage in late June and early July. Males usually emerge two to three days earlier than females, and emergence of the flies can last for up to six weeks. During the day, adults generally remain in the crop canopy where conditions are humid. In the evening, the females move to the top of the wheat canopy, laying eggs on the newly emerged wheat heads. Egg laying generally takes place in the evening or night when wind speeds are less than 10 kph (6 mph) and air temperature is greater than 10 degrees C. Upon hatching, the larvae crawl within the wheat glumes and feed on the developing kernels.

Hartley explains that wheat crops become susceptible to damage from the wheat midge “as soon as the boot splits and any part of the wheat head is visible or can be seen. The crop remains susceptible and you should be scouting until about 70 percent of the crop has reached anthesis (flowered) and the yellow anthers are extruded from the wheat glumes,” says Hartley.

If the wheat midge is present, and the crop is at a susceptible stage, scouting on successive nights is important to understand the development of the wheat midge population. The best time to scout is usually after about 8 p.m. when the female midge is most active. Hartley says that females are more active when the temperature is above 15 degrees C (59 degrees F) and wind speed is less than 10 kph (6 mph). When wind speeds are greater than 10 kph, egg laying may still occur on shorter, tillering heads within the shelter of the crop canopy.

Fields should be inspected at three or more locations in a field as midge densities and plant growth stages at the edge and centre of fields may be very different. The Saskatchewan ministry information indicates “that the highest densities are often next to fields where wheat was grown in previous years or in low spots where soil moisture is favourable to midge development. Often, midge infestations are higher at field edges with populations declining dramatically toward inner parts of the same field. In these situations, control around the field margins may provide adequate control and result in reduced cost. However, if midge densities remain relatively constant at all sampling sites, control over the entire field is warranted.”

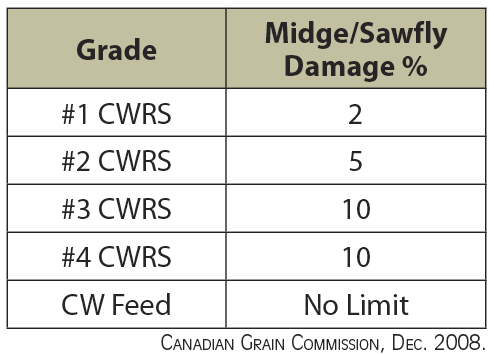

Prior to 2008, the economic threshold with respect to yield was one midge per four to five wheat heads, and was based on a yield loss of 10 to 15 percent. Using the same yield loss estimate, but with higher wheat prices in 2008, and taking into consideration the Canadian Grain Commission grading standards for wheat, the economic threshold was changed to one midge per eight to 10 wheat heads.

Grading tolerances for wheat midge damage to CWRS

Control when warranted but skip the revenge application

Research has shown that the best control for wheat midge comes from insecticides containing chlorpyrifos (Lorsban, Nufos, Pyrinex, Citadel), says Hartley. If the economic threshold has been reached when the wheat crop is susceptible, application can be made up to four days after reaching economic threshold. The reason for the delay is to allow more midge flies and wheat heads to emerge, and because it will take about four to seven days for the eggs to hatch. This timing allows the greatest level of control with chlorpyrifos, since the insecticide controls adult midge as well as eggs and newly hatched larvae. Only one application of chlorpyrifos is permitted annually.

Insecticides containing dimethoate are registered also, but this insecticide must be applied as soon as the economic threshold is reached. Two applications of dimethoate may be made per year, if necessary.

Hartley explains that once the wheat crop has reached advanced stages of flowering, insecticidal application is not recommended because the wheat crop is no longer susceptible to attack, and any larvae already inside the florets are unlikely to be affected by an insecticide. The insecticide also will have a negative impact on midge parasites. “It is often difficult to convince producers that late application of insecticides is unwarranted and costly, especially when large numbers of flies are hovering around the wheat heads,” says Hartley. “High commodity prices also resulted in reports of producers spraying just ‘to be on the safe side.’ At advanced flowering stages, larvae are unable to do much damage since wheat plants build up a natural resistance that tends to coincide with anthesis.”

For 2009, both Meers and Hartley recommend that farmers who have experienced wheat midge problems in the past, continue to scout their wheat fields when they reach the susceptible stage. While the wheat midge forecasts indicate that the risk is lower in 2009, the forecasts should only be used as one of the tools for monitoring wheat

midge risk.