Features

Insect Pests

Tackling the lesser clover leaf weevil

Looking for more options for managing this yield-limiting pest in red clover seed production.

May 26, 2021 By Carolyn King

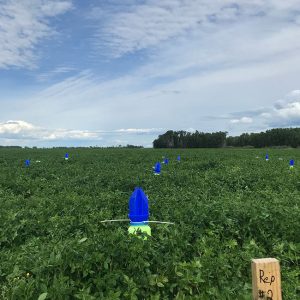

The lesser clover leaf weevil larvae damage red clover shoots as they crawl toward the buds and flowers. Photos courtesy of Dan Malamura.

The lesser clover leaf weevil larvae damage red clover shoots as they crawl toward the buds and flowers. Photos courtesy of Dan Malamura.

Despite its name, there is nothing “lesser” about the challenges in controlling the lesser clover leaf weevil (LCLW) in red clover seed crops. Now a project has assessed potential additional options for managing this tough-to-control pest so growers will be able to rotate their insecticides.

“The lesser clover leaf weevil is far and away the biggest pest and the biggest obstacle to red clover seed production in Saskatchewan. So it is a major pest of an important forage seed crop for growers here,” says Sean Prager, an assistant professor in plant sciences at the University of Saskatchewan, who led this project.

“This weevil is from Europe. It was first noticed as an invasive species in Saskatchewan in 1985 because it was causing problems in red clover seed production.” Red clover is the weevil’s preferred host, and the pest is a much greater concern in red clover grown for seed than for forage. Heavy infestations can lead to seed yield losses of over 50 per cent in red clover crops.

Both the adult weevils and the larvae damage the crop. The adults feed on the leaves and leaf buds at night. They overwinter mainly in the fields where they have been feeding. In the spring, they emerge, mate and lay their eggs within the stipules and stems of the red clover plants. The larvae crawl from their hatching site to the plant’s buds and flowers, feeding on the green parts, buds and flowers. Prager says, “When that happens, the flowers will abort, the buds will fall off, and the shoots will lodge.” And of course, seed yields will decline.

He notes, “The weevil has a few natural enemies, but they are not abundant enough to control it [sufficiently to prevent yield losses in seed crops]. So we need some kind of chemical control. Currently, the only active ingredient registered in Saskatchewan for this use is deltamethrin (Decis or Poleci).” This Group 3 insecticide is registered for suppression of the weevil in red clover seed crops.

Prager and his research group are interested in finding alternatives to Decis for several reasons. “One reason is that we’re hoping to identify something that is a little less harsh to bees [because bee pollination is important for high seed yields in red clover],” he explains.

“Another factor is that Decis is a contact foliar spray, but [the weevil adults] are moving around at night and the larvae are inside the stems, so the product is not necessarily going to come into contact with them.

“And third, we really want another insecticide option because relying on a single active ingredient for controlling the weevil increases the risk that the pest will develop resistance to that active ingredient.”

Assessing effectiveness and impacts

The three-year project evaluated the effectiveness of three different insecticides in controlling the LCLW in red clover and assessed the impacts of the insecticides on bee abundance. Dan Malamura, who is one of Prager’s master’s students, carried out the work. Project funding came from the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture’s Agriculture Development Fund and the Saskatchewan Forage Seed Development Commission (SFSDC).

Prager and Malamura compared Decis with two insecticides that are not currently registered for LCLW in red clover: Exirel (cyantraniliprole, Group 28), and Voliam Xpress (lambda-cyhalothrin, Group 3; and chlorantraniliprole, Group 28).

“We chose Exirel because it is systemic. Systemics, in theory, could have some advantages [over contact insecticides for controlling the LCLW]. For instance, in some cases systemics are less harmful to non-target organisms because they are absorbed into the plant rather than being sprayed as a foliar. Also with a systemic product, ideally you would get an extended period of protection and therefore you wouldn’t have to worry quite so much about the issue of these weevils moving around nocturnally or the larvae being inside the plant,” Prager explains.

“We chose Voliam Xpress because it is a combination of those two modes of action; it has both a systemic and a contact in it. The idea is that you’d have the best of both worlds in a way.”

The field experiments were carried out in 2018 and 2019 in six commercial fields in the Nipawin area. “We were very lucky to have had a whole series of Saskatchewan seed growers who would help us,” Prager notes. “So we were able to find fields suitable for the project each year. We used second-year red clover fields; typically you worry about the weevil in the second year because that is usually when you get flowering and seed.” All six fields had a history of LCLW damage.

At each site, Malamura set up a replicated block trial with multiple replicates to compare four treatments: Decis; Exirel; Voliam Xpress; and an untreated control where water was sprayed instead of an insecticide.

Malamura used a specialized backpack sprayer that allowed him to adjust the spray rate, pressure and so on to simulate a regular commercial spray application. He used water-sensitive spray cards to confirm that he was achieving the desired spray characteristics.

He applied the insecticides based on rates from the manufacturer and used a nominal threshold of six LCLW larvae per 10 clover shoots to decide when to spray. He rarely had to spray a plot twice.

To estimate the impacts of the treatments on bee populations, Malamura installed two types of pollinator traps – a blue vane trap and a set of three bee bowls – in each plot. He collected the pollinators from these traps several times over the course of the growing season, both before and after spraying. The bees in the traps were identified and counted.

To estimate the efficacy of the treatments for controlling the LCLW, he used two different methods in each plot. One method involved sampling clover shoots in the field and counting the number of living LCLW larvae. That sampling occurred three times: shortly before spraying, 24 hours after spraying, and 12 days after spraying. For the other method, he collected clover stems shortly before spraying and 24 hours after spraying. He put the stems in a growth medium and kept them in a growth chamber for 10 to 12 days, and then counted the living larvae and adults in each sample.

All three products improved yields

“Our most important findings relative to the insecticides were that all three insecticides worked pretty well in bringing down the weevil numbers compared to the untreated control, and all three resulted in greater seed yields compared to the untreated control,” Prager says.

“There were some minor differences in the time to become effective [for example, Decis provided better pest suppression in the first 24 hours after application than Exirel]. But ultimately any of them will control your weevils and reduce yield losses due to the weevils.”

Although the threshold they used for spraying did produce yield benefits, the project’s findings indicate that this threshold could possibly be improved. “Our work suggests the actual threshold might be somewhere between four and six larvae per 10 shoots,” Prager says. “There was visible stem and leaf damage on clover plants at densities below four LCLW larvae per 10 shoots, but it seems red clover can compensate for the damage later in the season.”

Another interesting finding was that there was no difference between the untreated and the treated plots in either the types of bees or the number of bees. Prager emphasizes that this result does not mean these insecticides have no impacts on bees.

He explains that various factors could have influenced how many bees were in the traps. “First of all, we were sampling small plots in a big field so it could simply be that there were lots of bees in those fields and even if the insecticides did kill some, they didn’t kill enough to change what was in the traps. Also, we applied the products based on the label instructions, which means being quite careful to not apply the insecticide when pollinators would be in the field. For example, we applied Decis towards the evening. So it is quite possible that no bees came into contact with this insecticide [while the residues were still hazardous to bees]. It is also possible that the traps were attracting bees from all over the field and that those bees were just going to the traps and maybe not visiting the insecticide-treated plants.”

Overall, they found that bee densities did not limit seed yields in these trials, but a lack of insecticide treatment resulted in significant seed yield losses when weevil pressure was high.

Possible next steps

If funding becomes available, Prager and his research group would like to look into several other LCLW control questions.

“The current threshold for spraying the weevil has not been really well tested, and our work suggests it could probably be optimized. We need to figure out exactly what the threshold and the timing should be,” he says.

“Also, it is important to pin down the rate for Exirel. Exirel is not well tested in red clover; they are working to get a minor-use registration for it now. In our project, we used rates recommended by the manufacturer [based on other weevils in other legume crops]. Since Exirel is about five or six times more expensive than Decis, it is very important to try to find the minimum appropriate rate, how frequently or infrequently to spray, all those sorts of things, to make it a viable option for growers to include in insecticide rotations.”

Prager is also interested in evaluating some other insecticides that might be good rotation alternatives for Decis.

As well, Prager’s research group had been planning to help the SFSDC to partner with a company specializing in automated sprayers, in an LCLW project in 2020. The project was postponed due to COVID-19, but Prager hopes it will go ahead in the future. “We were going to try using the automated sprayers to spray at night. We think it might be more effective to spray overnight when the weevils are moving around and the pollinators are not in the field.”

Such studies could help put more of the pieces in place for improved management of the lesser clover leaf weevil in red clover seed crops.