Features

Canola

Diseases

Tackling clubroot

Disease updates, reducing risk and practical management tips.

June 18, 2020 By Presented by Dan Orchard, Canola Council of Canada & Curtis Henkelmann, central Alberta canola grower at the Top Crop Manager Plant Health Summit, Feb 25-26, 2020, Saskatoon.

My name is Dan Orchard and I’m an agronomist with the Canola Council of Canada at Wetaskiwin, Alta. I guess my claim to fame was the first discovery of clubroot in canola. A farmer called me because he had a problem in his canola and he didn’t know what it was. I helped identify it, so I guess my claim to fame is kind of the inventor of clubroot in Alberta.

Curtis: Well, that’s how I got to know Dan back in 2003. We farm just south of the Edmonton International Airport area. We’re spread out about 30 miles across and we crop about 4,000 acres. I figured out that we move 96 times down the road, in and out of about 128 parcels of land. In ’03 when we discovered this disease, it was quite devastating at the time. But, hey, we’re here today, and at the point now where we feel that we’re seeing a reduction in what we had initially.

Dan: I realized that the county south of where I discovered clubroot on Curtis’s farm was just as bad, but nobody knew how to look for it or what it was. So, I think one of the big take-home messages here is that you need to find clubroot early. You need to look for it.

Some other key points are to keep your spore loads low. The lower your spore load, the easier clubroot is to manage. We have incredible resistant varieties, but when they’re overused, they’re not going to last forever.

I think it’s also important for everyone to understand that as an agronomist or as a consultant or as a farmer, you need to always be thinking about a clubroot management plan because this is a very controllable, manageable disease if it’s proactively managed. If we wait until we can see huge patches of clubroot, we’re behind the eight ball.

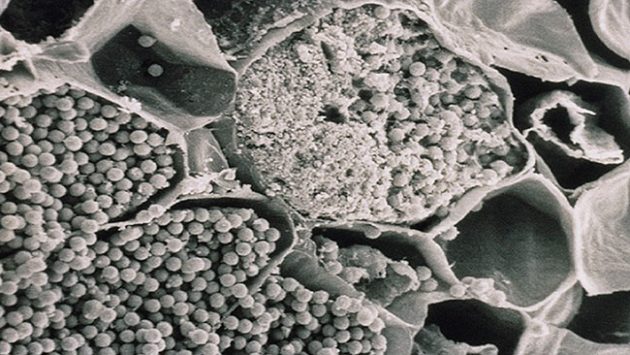

Plant cells are meant to be hollow to transport water and nutrients. Instead clubroot plugs the cells with microscopic clubroot spores, and that keeps the plant from up-taking water and nutrients. It’ll wilt and potentially die. You could fit 10 clubroot spores across the width of a human hair, and, in my opinion, this is why it’s so difficult to control and so prolific.

How is it spreading? Canola propagates clubroot but it doesn’t spread it. Moving soil spreads clubroot. Whether you’re growing barley or wheat or oats or just tilling your land, that’s what’s moving clubroot around.

When I first met Curtis, he was the first and only person to sanitize every piece of equipment.

Curtis: This was kind of a double-edged sword at the time. I was working for the municipality on the enforcement side of clubroot management. With our farming operation, we had to follow a protocol. We started with sanitization, and worked with it for about three years, and basically, it was impractical. You can’t clean every piece of dirt off your equipment, wash it and then sanitize it. We now blow or brush off the majority of the dirt that we can every time we move from a field, which has become a practical way. It takes a little bit of time – half an hour each time to move – but the whole thing with our operation – we’ve followed a plan.

We had a lot of oil field activity, and we thought maybe it was a salt spill or it was something from the past. Actually, it was a clubroot infection. Once we’ve identified these areas, we’ve avoided them, and I believe it’s helped us gain the opportunity to educate anyone we interact with on the farm. We have people coming on the land: surveyors and hunters. I tell everybody where it is so the patches can be avoided.

Dan: It would be a stretch to say that anyone in Curtis’s area doesn’t have clubroot. It’s unfortunate that the stigma is still there, and that people hide it for some reason. But I think in the heart of the clubroot area now, it’s just understood that you need to let people know where it is so they don’t drag it to their farm, or you don’t drag it over your whole farm.

The entrances and some of the hotspots are areas where Curtis can tell people not to enter or not to park there. I do think that the shocking part is how much soil we move with our equipment. We can point the finger at oil and gas, or exploration, or hunters, or deer, or geese, but we’re moving clubroot mostly with our farm equipment.

Curtis: I’ll give you a small example. A nutrient company was in a neighbour’s field, and we had one of those spring downpours, and the truck was stuck. The following day the truck was pulled out and it went to another neighbour’s place down the road. He was unloading the truck, and the guy kicked the mud flaps off. Exactly where that area was, a year later with canola, there were these small eight-inch patches of clubroot. Within a three-year period on the next canola crop, and that was an area that was worked quite a few times, there’s a 25-acre patch. That’s how easily it moves.

Dan: There are other ways of spreading that are out of the control of the farmer as well. Research has tracked wind trajectories that originated from Edmonton, and where they were deposited in various parts of the Prairies. There were two wind events that were tracked to carry dust particles that originated in Edmonton, with some as far east as Portage la Prairie, Man., and up into the Peace River region to the northwest.

Curtis and I have both seen trends downwind from bins or areas where dust collects in your field, and that is where clubroot can often be found quite easily. Intuitively, I think we knew it was spreading in the dust from other crops, as well.

When you harvest wheat, the dust will have clubroot spores in it, too. In the seed cleaning plants all around our area, tailings and dust from all crops have clubroot spores on the dust.

Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba all have a little different way of reporting. They’re trying to unify the map across Canada, but I don’t know that we’ll ever get there because Alberta is not testing soil, because it would be a waste of money because it is everywhere.

Manitoba reports by the number of spores per gram of soil and when you overlay that with the frequency of canola in rotation, it’s not a surprise there is a correlation.

Saskatchewan reports by municipality with clubroot detected in soil samples, and by visual symptoms. Alberta has now switched to total number of cases affected by clubroot per county. But that has issues, because where Curtis farms, they’re one of a few counties that look at every single canola field, so they’re going to find many more fields than the counties who don’t survey as many fields.

Curtis: I can elaborate on that. Working at the county for about 18 years, they still, to this day, try to inspect every field. The problem is in the surrounding municipalities where they don’t inspect every field. You can identify clubroot by driving down the road at 100 kilometres an hour. You can see it, but they have their heads in the sand. That’s really troublesome for myself and a lot of producers that are trying to manage it, because these other MDs and municipalities, they just seem to brush it off and rely on genetics.

Dan: Researchers and industry came up with this clubroot management recipe in the last few months. I find it kind of ironic because in talking to other farmers in the heart of the clubroot region, they’ve been following this recipe for years and years, not because we told them but because they’ve found ways to successfully farm with clubroot.

Clubroot management recipe

- Scout. Scout. Scout

- Have at least a two-year break between canola crops

- Use R-rated varieties before clubroot gets established

- Avoid movement of soil and make sure incoming equipment is free of soil

- Control host weeds and volunteer canola

- Use patch management strategies

Scouting for clubroot is unbelievably important. A two-year break from canola is a saviour for canola production. Recent research that’s been repeated numerous times is showing that 90 per cent to as many as 99 per cent of the spores are not viable after a two-year break. A three-year rotation or that two-year break is probably the biggest thing to combat clubroot if it’s done proactively. You can’t wait until clubroot arrives and then extend your rotation. Using resistant varieties is huge.

Curtis: We’ve been on primarily a three-year rotation – sometimes four. We’ve also been using a resistant variety. In the last four years, on average, we grow 1,200 acres of canola. The county inspects every canola field and in the last four years, we haven’t received an Information Notice, which is issued if they find clubroot on less than 30 plants per 100 canola plants inspected in a field. So we know our clubroot pressure is going down. Unfortunately, we had 26 inches of rain over this past growing season and we have 3,000 acres of ruts, and we have to work the whole thing. I’m not happy about it, but I feel fairly confident that we’re going to contain the spread just by what we’ve been doing.

Dan: It is really important to control host weeds, minimize soil movement, and manage patches. Managing patches means dealing with that patch. You don’t ignore it and keep working the land and spread that patch out across your whole farm. Maybe you grass that patch. There’s evidence that grasses will drive the spore load down much quicker than not having grass there. For Curtis, some of his patch management is just simply telling people not to go work that piece in the corner because there’s clubroot there, right.

Curtis: We’ve actually grassed a couple areas because it doesn’t produce anything anyways because of compaction from pulling in and out of the field. I look for the offsite of the prevailing wind, especially where you have a bush line. That’s where we’re seeing the higher levels of clubroot. Another area is some of the old yard sites that are higher in fertility that have higher clubroot.

Dan: We’ve seen a lot of old garden sites where they grew cabbage or broccoli or some susceptible Brassica crop in the past that was the source of clubroot. Then you can watch it spread to the whole field. I’ve seen wheat straw bales that have been piled on the edge of the field for a few years and when the bales are removed and canola seeded, the canola dies in the shape of where the bales were. It was because of the dust on the straw carrying clubroot spores.

Mary Ruth McDonald at the University of Guelph looked at how many spores are needed to start showing clubroot symptoms. These numbers aren’t exact, but typically you need 10,000 to 100,000 spores in one gram of soil, which is about the size of a loonie, to consistently see clubroot symptoms. In Alberta, we’re at a million or millions of spores in one gram of soil so we see symptoms all the time.

In Saskatchewan and Manitoba, you’d be at 30,000 or 10,000 or less. The key in these provinces is to do a two-year break and the spore load would become almost be not detectable. In Alberta even starting at 100,000 spores, with a one-year break, the spore load goes up into the millions. Even if 99 per cent of the spores die within that first two years, at 100 million spores in a gram of soil, one per cent survival is still a million. That’s the problem with not proactively managing clubroot – the spore loads get so high that they just can’t be controlled in a rotation.

Pull plants to scout for the disease. We originally thought the way to scout for clubroot was to drive down the road at swathing time and look for a big dead patch, but we’ve since learned that’s far too late to be discovering it. Every single time you can, stop the swather and pull plants.

When you are scouting, you want to find plants with very mild symptoms, because it is very, very early and very easy to manage. A two-year canola break, controlling host weeds and growing a resistant variety could be adequate. In Alberta, we have seen entire fields not harvested due to severe clubroot infestation. That shouldn’t happen in Saskatchewan and Manitoba because you have so many more tools and information than we had when we started.

Curtis: Back in ’05, there was a field outside of the International Airport at Edmonton. It was 120 acres, the grower couldn’t fill a John Deere 9600 combine hopper off that 120 acres. That was quite devastating at the time.

Dan: Crop rotation is so important. I looked at AAFC Annual Crop Inventory Maps to see how often canola is grown in rotation. I chose western Manitoba and eastern Saskatchewan from 2009 to 2014. The map covers every 80 acres, and suggests that in a lot of cases, every second year is canola in this area, and probably three out of five years or four out of six is in canola. That crop rotation is like Alberta’s was in the 2000s.

Curtis: One principle we operate on is a margin basis. We don’t look at the margin we make off of canola. We look at it over wheat, peas, barley, and canola. We average it out. A lot of people don’t do that. A lot of farmers that I talk to still think resistant varieties are the silver bullets, and it’s not. It’s the whole management practice, and you can’t reduce that rotation.

A little footnote, there’s a farm family in the area and they refused to change their practices. They have had a few Notices. Someone has been going out to their equipment every morning and leaving a jug of bleach sitting on the step. This has happened probably 25 times now, so we nicknamed these guys “the bleach brothers.” Finally, this year, the county has stepped down on them, and they had nine quarter sections restricted for canola growth for five years.

Dan: Grow resistant varieties. Here’s a picture where a father and a son farmed a quarter section, and they had an argument on whether or not they should grow a resistant variety. The son grew a non-resistant variety because it had higher yield potential and Dad grew a resistant variety. The resistant variety yielded about 50 bushels and the other five bushels. The moral of the story is “listen to your dad.” When you’re picking a variety, yield doesn’t have to always be the number one selection.

Resistance management is also important. If you have high spore loads and grow canola too frequently, you’ll select for different pathotypes in the field. Up until last year, we thought there was between 16 and 19 strains or pathotypes of clubroot. Now, that’s up to 36 pathotypes. There’s so many strains out there that there’s absolutely no way that breeding is going to take care of this. It’s just one tool in the toolbox.

Curtis: Some growers, because of the cost of some of the resistant varieties, have mixed a resistant and non-resistant variety together.

Dan: Yeah, that’s not recommended. Initially, the first generation of resistant varieties was effective against only few pathotypes. Now, there are 19 pathotypes that have overcome that resistance. There are a few new genetic sources that are able to control some of these new pathotypes, but we have no idea how many and which ones because the new material hasn’t been screened, and these pathotypes were just discovered last year. It’s a mess, believe it.

We’re up to hundreds of fields that are showing clubroot symptoms in a resistant variety, but that’s in the fields that have been reported. There would be hundreds alone in Curtis’s county. So, the numbers are dramatically underrepresented. I think that there’s thousands and thousands of fields that have broke resistance that we just don’t look for, or we don’t believe it, or it’s too difficult to find without intensive scouting.

As I mentioned, equipment sanitation is another important part of the recipe. For farmers, the most practical thing is to knock off dirt at grassed entrances and exits before moving equipment.

Curtis: I’d say it takes half an hour. If you do it all the time, we don’t notice it anymore. But the last year was pretty challenging in the fall with ruts from grain carts and Super B’s stuck all the time. We left the loader at every approach, and we pushed the mud into the field because we felt that obligation. We run a closed system, so we know we’re not letting anybody else on our land. No more custom operators or hunters. But in our area there are a lot of custom manure hauling and silage outfits. They seem to be the ones that are really moving it a distance.

Dan: I was called to a field last year with a resistant variety and we went fencepost to fencepost, looking for clubroot. It was bad because he pretty much broke every rule. He used a high-speed tillage unit and grew canola, wheat, canola, wheat, canola, and wheat. It was his fifth time he was growing a resistant variety of the same genetic source. He dragged clubroot to every corner of his field and farm. He had a lineup of neighbours who all wanted to borrow his high-speed unit, and this undoubtedly spread around the county.

Researchers have captured dust blowing off fields with clubroot, and found up to 220,000 spores in a gram of dust, so we need to reduce our tillage. On boots, a Swedish study found boots can carrying 140 grams of soil and had concentrations of 600,000,000 spores per gram. That is 84,000,000,000 spores on each boot. Undoubtedly, you could spread clubroot with your boots as an agronomist, with a quad, with your truck.

Weed control is something else that I think we do quite a good job of, but I don’t know that we’re removing the weeds early enough. A recent study has shown that three weeks after the weeds emerge, clubroot spores are viable to carry on the next generation. If we don’t kill Brassica weeds until five or six weeks after they emerge, they’re likely contributing to the spore load in the soil.

Often we see a clubroot the size of a table. I don’t think it’s completely unrealistic to go out and pull these awful-looking plants out of the ground and burn them. The vegetable growers do that, and then they put lime on and seed the patch to grass. We still need to have more research on liming. I’ve seen amazing results, but our soils are so variable that we need to have more research on the 4Rs of liming.

Plants like ryegrass and brome grass that have a really dense, fibrous root explore more soil, and come into contact with more spores. When the spores come out of dormancy, they have no host plant to attack, and they die off. Research was shown that after grassing a heavily infested patch, 90 per cent of the spores were not detectable anymore.

I like the recommendation to grass entrances and exits. It’s a little easier than grassing patches out in the field.

Curtis: It’s easier. I will say it’s a bit of a pain. We have grass in places that we don’t really want it, but it’s helped us. It has helped reduce the spread.

Dan: We have a long list of resistant varieties. There’s not a big premium, if there is a premium at all. To understand the genetic sources or resistance behind them so that you can rotate those genes, I recommend you talk to your retails and your seed companies. The time to start using them is now, even if you don’t think you have clubroot.

Curtis: Another thing we’ve done is if we had a really bad field, we would leave seeding it until the last, but we still try to clean everything off when we’re done. We’ve been dealing with clubroot for 18 years now, and we’re at the point where we’re comfortable in our rotation and management practices. I believe we can continue to grow canola by following just these small practices.