Features

Agronomy

Plant Breeding

Still nutritious after all these years

A scientific study is proving that Canadian wheat varieties today are as healthful as those from the 1800s. In this photo, a researcher analyzes wheat samples for bioactives, such as lutein, which plays a role in maintaining eye health.

Photo courtesy of AAFC.

One of the common criticisms aimed at wheat nowadays in the media is that breeders have genetically modified wheat varieties in recent decades to the point that it is detrimental to human health. These claims have been made despite the fact that modern wheat varieties have been developed steadily over the last century using only conventional breeding methods. Now, a scientific study is proving that Canadian wheat varieties today are as healthful as those from the 1800s.

“The study was prompted by a couple of factors. One is that there is a lot of interest in this issue from consumers and the public, with people wondering if some of the original wheat varieties grown in Canada, like Red Fife, are healthier or better tasting than the wheat we’re producing now,” explains Dr. Nancy Ames, a cereal research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC).

“Second, there has been a lot of discussion in the popular media claiming that modern breeding has had negative effects on wheat’s nutritional qualities, so we wanted to investigate whether any such changes have occurred in Canadian wheat.”

Ames collaborated on this study with Dr. Ron DePauw, a wheat breeder at AAFC, and Dr. Nancy Edwards, who was with the Canadian Grain Commission when the study started in 2011. They compared 20 western Canadian hard red spring wheat varieties. These included three heritage wheats from the 1800s – Red Fife, Ladoga and Hard Red Calcutta – and 17 varieties, ranging from Marquis, registered in 1904, to CDC Utmost, registered in 2010. DePauw grew the varieties at Indian Head and Swift Current, Sask., for four years. While DePauw evaluated their agronomic characteristics, Edwards analyzed their milling and baking properties, and Ames measured their nutritional characteristics.

Ames already knew from her own research and many other scientific studies that wheat has a wide variety of healthful components. In this study, her research group is measuring nutritional characteristics in whole wheat flour from samples of each of the 20 wheats, grown at each site, for each year of the project.

Her goal is to generate adequate scientific evidence to counter the negative media claims about wheat breeding and its impact on wheat composition. In addition, her research aims to demonstrate the variations in bioactive compositions with different varieties to facilitate breeding of new cultivars with enhanced health benefits, without compromising agronomic performance and processing quality.

Ames and her lab have just about finished the analysis. She says, “We’ve looked at basic nutritional profiles for components like carbohydrates, fat, fibre and protein, as well as more detailed analysis of bioactive compounds that could have significant human health benefits. For example, available carbohydrates and starch-fibre ratios were measured because those ratios can be implicated in glycemic response. We’ve looked at total protein as well as the ratio of gliadin and glutenin, which are the two proteins that form gluten. Wheat is a rich source of polyphenolic antioxidants, which have beneficial effects against major human chronic diseases. Therefore, we’ve looked at total phenolic content as well as six individual phenolic compounds, which vary depending on variety, stage of plant growth and growing location.”

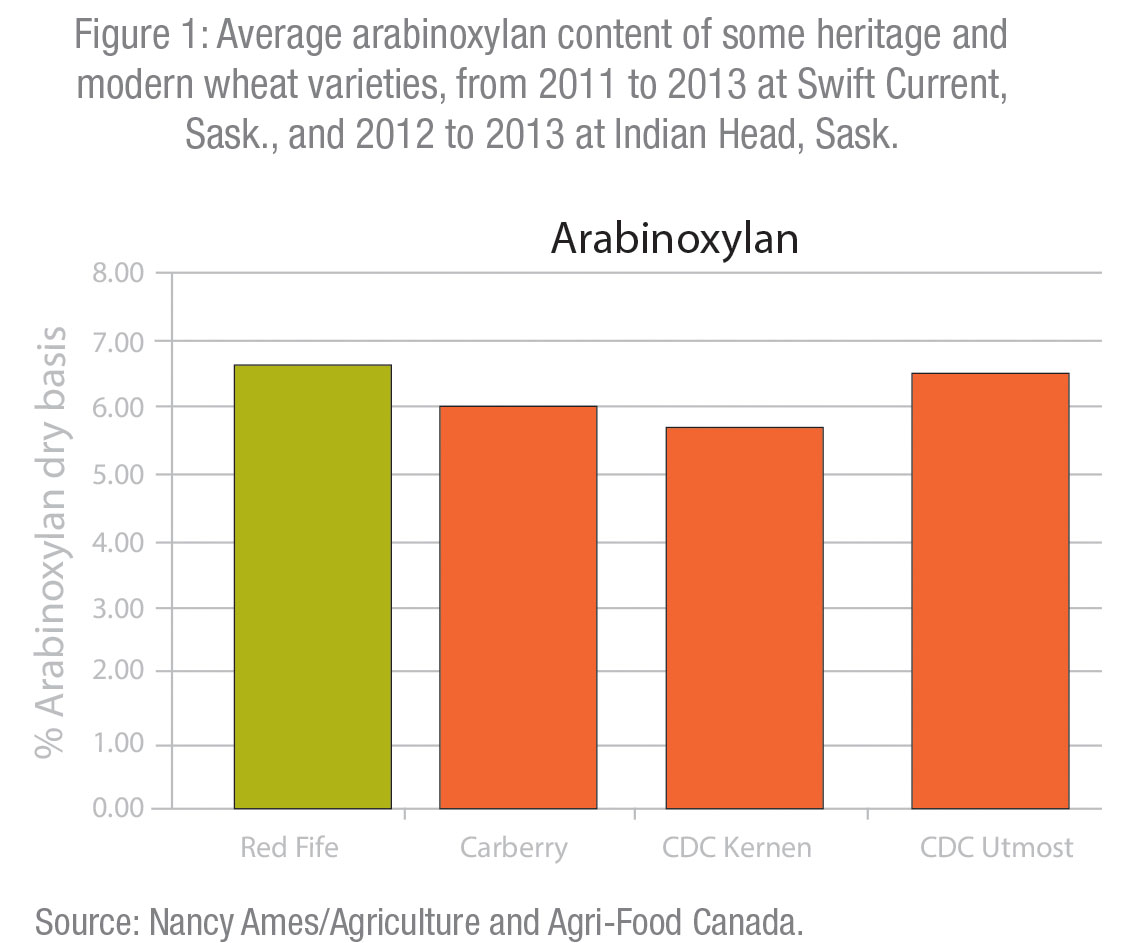

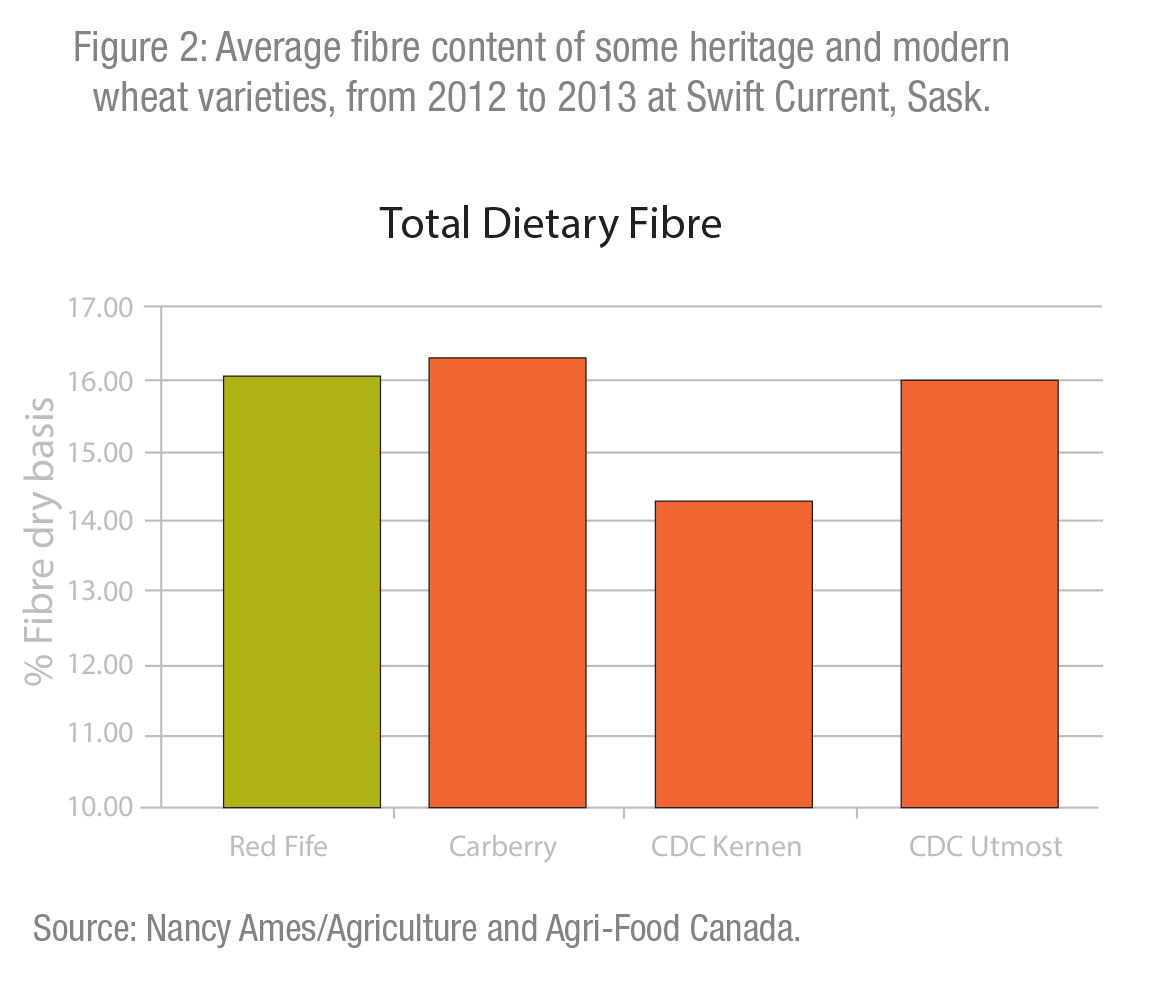

The researchers are also measuring the levels of specific types of fibre such as arabinoxylan (known for its role in reducing glycemic response), insoluble and soluble fibre, and two lesser known wheat bioactives: betaine and lutein, which play roles in reducing inflammation and macular degeneration, respectively.

The data show genetic variation in the levels of the different nutritional components, as you would expect, but no strong trends, either positively or negatively, between the older types like Red Fife and today’s varieties. For instance, Figures 1 and 2 show some of the results for arabinoxylan and total fibre contents.

“Breeders have not selected for most of these nutritional components,” explains Ames. “They have focused breeding efforts to maintain end-product quality and improve agronomic performance, so it is good to know that none of these nutritional components have been lost.”

She adds, “The Canadian wheat industry keeps a very careful watch over the quality characteristics of our wheat varieties in Canada, ensuring bread making quality is maintained. Wheat varieties like Red Fife and Marquis were known for making really good bread. So breeding of hard red spring wheat has emphasized maintaining or improving that quality, while working on developing cultivars with superior yields and resistance to disease and insect pests.”

Ames points to another interesting finding from the study: “For a lot of the newer varieties, the levels of the nutritional components were maintained across the different locations and across the three years. But some of these characteristics in older varieties were less uniform across environments.”

According to Ames, the greater uniformity of the more recent wheat varieties is likely due to advances in our wheat breeding programs, such as having more locations and more testing of breeding lines. She notes, “The uniform quality of Canadian wheat is an important characteristic for marketing wheat domestically and internationally. No matter where in Western Canada a farmer is growing wheat, buyers can count on the quality.”

Even healthier wheat products?

Could our wheat varieties and wheat products be even more nutritious? “There is always room for improvement,” says Ames. “Those improvements could be made through breeding, changes in processing, and genotype by environment interactions. From our work on the heritage wheat varieties and from previous studies, we know there is genetic variation for nutritional components. We also know that nutritional characteristics have not been actively selected for in most wheat breeding programs. This is unlike the oat breeding program, where emphasis is placed on increasing cholesterol-lowering fibre components to meet the well-known health claim. Therefore, with the use of appropriate screening tools, it is possible for breeders to further improve the nutritional content of modern wheat lines.”

Canadian wheat breeders have already proven their ability to enhance wheat characteristics for production of healthier end-products. “When breeders decided to focus on the type and colour of bran, they were able to develop hard white wheat. It has the same bread making quality as hard red wheat, but it has a different bran and end-product colour that is preferred by consumers. That change allowed millers and bread makers to produce high fibre whole wheat products that still looked more like white bread,” notes Ames.

From the processing side, using whole wheat flour – flour made with 100 per cent of the kernel – rather than flour made from just the endosperm really boosts the nutritional value of wheat products. The endosperm has starch and protein, but most of wheat’s beneficial components are found in the rest of the kernel. The germ has protein, lipids, folic acid and vitamin E; the aleurone (the layer surrounding the endosperm and germ) has fibre, niacin, thiamine, iron, protein, antioxidants and bioactives; and the bran layers (the kernel’s outer layers) have fibre, antioxidants, B vitamins, minerals, protein and other bioactives.

Various studies have shown healthful benefits from consuming whole wheat products. To give just a few examples, wheat bran fibre consumption has been shown to increase satiety (making you feel fuller faster), lower weight and improve insulin sensitivity. Wheat germ consumption has been reported to reduce the cholesterol absorption from the diet. Increased intake of whole grains is also associated with lower fat tissue levels in adults. Ames says, “This considerable scientific evidence strongly suggests that regular whole grain wheat consumption will have significant beneficial effects against obesity and associated metabolic diseases.”

In her own research, Ames is really excited about the interaction between variety and the resulting whole wheat product. “For instance, there are opportunities for improving wheat lines specifically for use in whole wheat end-products.”

This type of research could lead to the development of a wider range of whole wheat products that more consumers would find just as scrumptious as regular wheat products, while also enjoying the nutritional benefits gained from including the bran, aleurone and germ.

However, Ames emphasizes that for breeders to start developing new varieties and wheat processors to begin developing new food products, they have to be sure there’s a market. And to develop a bigger market for more nutritious wheat products, consumers need better information on wheat nutrients.

“Consumers have a lot of influence over the products that food processors produce, which is why it is important for consumers to have all the science-based information they need when making healthy food choices,” says Ames.

With no-wheat and low-carb diet books putting wheat on consumers’ radar these days, Ames thinks it’s an opportune time to give the public more complete, scientifically based information about wheat’s nutritional profile.

“Many people don’t realize that wheat has a lot of healthy compounds that are quite important to our diet. For example, whole wheat and bran products are an important source of insoluble fibre, but wheat also contains less well known bioactives such as betaine, lutein, antioxidants and arabinoxylan. Wheat is also a source of protein – gluten is a protein complex in wheat – with both functional and nutritional benefits.” She notes that gluten, like any protein, has the possibility of causing an allergic reaction, but most people are not allergic to gluten, and only about one per cent of the population has celiac disease.

Ames says, “I think it’s our responsibility, from a scientific viewpoint and from a wheat industry viewpoint, to provide consumers with the information that they deserve to know in a concise and easy-to-read story so they can make informed choices.”

January 8, 2015 By Carolyn King