Features

Agronomy

Diseases

Spike in blackleg raises concerns

Growers have come to rely on planting blackleg resistant canola varieties as a strategy for managing the disease. However, many growers across Western Canada have been tightening their rotations to take advantage of economic opportunities, a practice that can increase the risk of blackleg developing and blackleg resistance being eroded or overcome.

Researchers and industry are concerned about recent developments and are working to develop strategies to reduce the risk of losing the durability of current gene resistance.

“Over the past few years, especially in 2012, we have seen a bit of a spike in blackleg disease in canola across Western Canada,” says Dr. Gary Peng, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. “We are not sure if it is the beginning of a new phase of the disease or if it was mostly related to the environmental conditions in the spring of 2012 that caused higher levels of infection in some areas. However, the biggest concern is that in isolated fields some of the R-rated varieties were badly damaged, responding more like a susceptible variety than a resistant variety.”

Researchers and industry have been concerned about the potential breakdown in blackleg resistance for some time. New races have been isolated that are overcoming resistance in Australia, Europe and Canada, sometimes in as little as three years. “We are currently doing research to look at the composition of the pathogen race structure in the fields where we saw severe damage this year,” notes Peng. “We are also looking at the overall race structure of the pathogen and where these races occur across the Prairies, because to be able to manage the disease effectively with genetics, we need to know what the pathogen populations are.”

Canola breeders can use both quantitative and qualitative resistance to develop blackleg resistant varieties. Quantitative resistance is largely due to many genes, each with a relatively small effect. Qualitative or specific gene resistance acts in a gene-for-gene fashion between avirulence (Avr) genes of Leptosphaeria maculans (the pathogen that causes blackleg) and the matching resistance (R) genes in the plant. Resistance only results if both the Avr gene in the pathogen and the corresponding R gene in the host are present; otherwise, a susceptible reaction results and disease symptoms are observed.

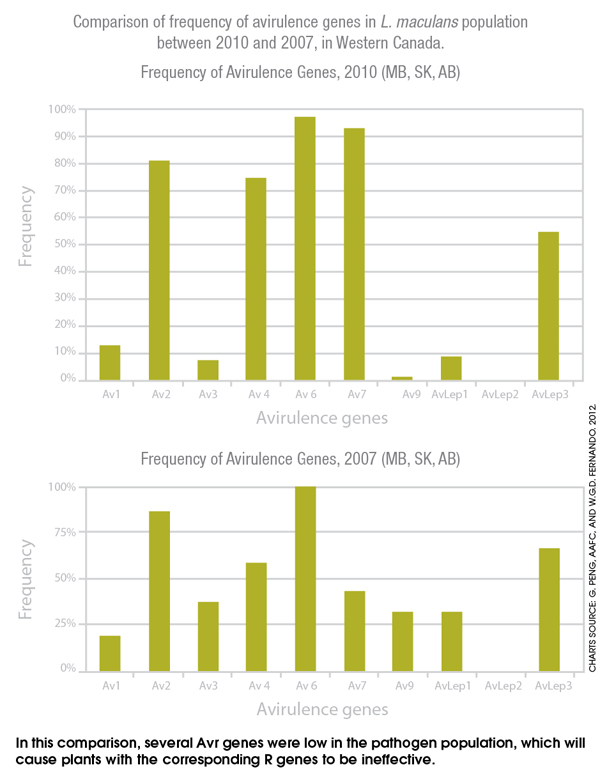

Previous research has identified at least 14 avirulence genes effective against L. maculans. “We have several research projects in collaboration with Dr. Dilantha Fernando at the University of Manitoba, including one where we have compared the pathogen race structure across Western Canada in 2007 and in 2010, and most recently analyzing results for 2011 and 2012,” says Peng. “Generally several Avr genes were low in the pathogen population, which will cause plants with the corresponding R genes to be ineffective. For example, the Av3, Av9 and AvLep1 showed substantially lower frequencies in 2010 than in 2007, which means cultivars with those specific resistance genes will not be effective.”

Although most commonly grown varieties of Brassica napus canola carry moderate to high resistance to L. maculans, the type of resistance or the specific genes for resistance present in a variety are not generally known. “In another collaborative project, Dr. Fernando’s group characterized the R genes in about 100 commercial cultivars,” says Peng. “Not surprisingly, we are finding that most of those R genes are Rlm1, Rlm3 and occasionally a few others. About 80 percent of our current cultivars have Rlm3 or Rlm1, making the resistance spectrum very narrow in the majority of our cultivars.”

On the positive side, researchers are finding that many of the companies have also included a strong selection of quantitative resistance in the genetic background, which can provide a wider range of activity against different races.

“This is likely why the breakdown in resistance has been isolated so far,” notes Peng. “It also gives plant breeders an opportunity to consider including other R genes that haven’t been used much, such as Rlm4, Rlm7 or Rlm6, in any of the varieties with high resistance, and when combined with quantitative resistance, will result in much more durable cultivars.”

Peng is optimistic that in the long run, looking at both the pathogen and resistance aspects in combination with practical management practices should allow industry to manage the disease effectively.

Risk assessment and management

Growers are encouraged to look at blackleg management in terms of risk assessment and risk management. “We know that resistance genes are not infallible and they do break down, as we have seen in isolated fields across Western Canada,” says Clint Jurke, agronomy specialist with the Canola Council of Canada (CCC). “We have found some fields where R-rated canola varieties had high levels of blackleg, but it has been fairly isolated to individual fields and all comes back to the grower’s rotation. Usually the problems are in fields where growers have been on a tighter rotation and have used a single variety or a similar variety in that tight rotation, which puts the same type of resistance under pressure.”

Growers should assess the risk of the various blackleg management practices they plan to use in their canola cropping system and select appropriate strategies depending on whether they are at a high or low risk of disease pressure. For example, growing canola in a tight rotation (canola more frequently than one in three years) will increase the risk for development of blackleg and the risk of blackleg resistance being eroded or overcome. If growers make one management decision that is high risk, then they should be making another management decision that is low risk to balance that out.

Tight rotations are high-risk behaviour, so will need to be balanced with rotating varieties that have different resistance backgrounds, scouting and characterizing fields for disease pressure, and possibly including fungicides to try to reduce some of that disease.

“The conclusion of much of our research over the past several years has confirmed that lengthening the rotation is still the best strategy for managing blackleg,” says Dr. Randy Kutcher, research scientist at the University of Saskatchewan. “The pathogen overwinters on the lower stem and upper root pieces, which can take two to three years to break down and up to five years during a series of dry seasons. With the most popular rotation in much of the Prairies going to a two-year rotation, there is a continuous buildup of those woody bits. We have tried experiments with practices such as cultivation or conventional tillage or even burning, but none of them got rid of the canola residue.”

Fungicides are another option, but so far research hasn’t shown them to be a very effective option as compared to rotation or resistance. “[Fungicides] provide a third management tool if resistance fails or if growers are using a tight rotation,” says Kutcher. “Fungicide treatments are more of a rescue measure if other options fail.”

Peng agrees and adds that continued research is showing that if a grower has a variety that has completely lost resistance and applies fungicides early enough to deter the infection on the cotyledons, or lower leaves, then fungicides might be a choice at that time. However, pathogens can also easily develop resistance to fungicides, so repeated use is not recommended.

“We were also surprised this year how industry at large seemed to have lost the skill set for identifying blackeg in the field,” says Jurke. “Some fields with blackleg infection were being misidentified as having brown girdling root rot or sclerotinia stem rot. So learning to identify blackleg symptoms and scouting is very important.”

Growers should scout fields early in the spring, but most importantly, scout at swathing to assess the amount of blackleg infection in the crop. Take clippers to the field, pull the roots of a few plants out of the ground and look for blackened tissue inside the crown of the stem. The amount of infection present will help identify the level of risk and the best management practices for that field in following years.

“We are looking forward to the results of the research on pathogen races and characterization of the resistance genes in the available commercial varieties,” says Jurke. “This information will help growers determine what variety they should be planting in sequence in the field. We hope to have this information available before spring of 2013.”

Although many varieties possess one resistance gene, some varieties have multiple resistance genes, which makes them more durable and more difficult for the pathogen to overcome. Growers, researchers and industry have to work closely together and implement best practices to reduce the risk of losing blackleg resistance and protect the profitability of the canola industry.

Rating blackleg severity

The Western Canada Canola/Rapeseed Recommending Committee (WCC/RCC) rates diseases incidence and severity in blackleg. The severity of blackleg infection is evaluated on a minimum of 100 plants averaged over four replicates at crop maturity. Individual plants are uprooted, cut through the basal part of the stem and scored on the basis of the amount of disease present using the following 0-5 scale:

0 – No diseased tissue visible in the cross-section.

1 – Diseased tissue occupies up to 25 percent of the cross-section.

2 – Diseased tissue occupies 26-50 percent of the cross-section.

3 – Diseased tissue occupies 51-75 percent of the cross- section.

4 – Diseased tissue occupies > 75 percent of the cross-section with little or no constriction of affected tissues.

5 – Diseased tissue occupies 100 percent of the cross-section with significant constriction of affected tissues; tissue dry and brittle; plant dead.

February 28, 2013 By Donna Fleury

Blackleg symptoms on a canola leaf. Growers have come to rely on planting blackleg resistant canola varieties as a strategy for managing the disease.

Blackleg symptoms on a canola leaf. Growers have come to rely on planting blackleg resistant canola varieties as a strategy for managing the disease.