Features

Other Crops

Spelt versus quinoa – which would you choose?

Two novel names in crops for Western Canada are spelt and quinoa, both of which could supply an option to traditional wheat, barley or oats.

August 22, 2019 By John Dietz

Photo by Top Crop Manager.

Photo by Top Crop Manager. Spelt and quinoa are growing in popularity in Western Canada, showing up more often in the farm press, field trials and where you buy food. Should you be interested?

People growing quinoa and spelt today may be the pioneers of tomorrow, according to specialists at various Manitoba Agriculture Diversification Centres located across the province.

For a long time, hemp was a novelty crop in Western Canada, and for a previous generation, soybeans in particular were a novel crop in eastern Manitoba.

“With novel crops, there’s a requirement for a lot of energy and focus on early development, both agronomically and economically,” says James Frey, diversification specialist in Parkland, Man. “Without the people who championed hemp as pioneers, it wouldn’t be what it is today – a fairly common crop in western Manitoba.”

Seeded acres

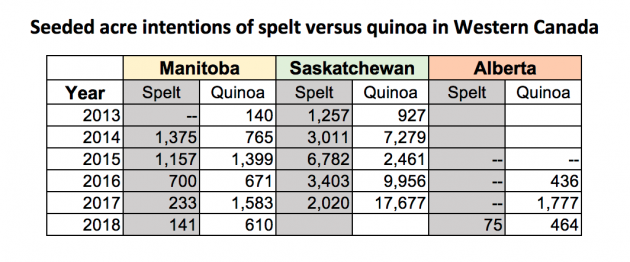

Provincial crop insurance officials keep reports of seeded acre intentions, although it is likely that more acres are being grown. While quinoa is leading spelt in seeded acres, both are in significant demand by health-conscious consumers as alternative foods.

They can produce a good return per acre. Both can be reliable, if well-managed. But, the novelties have risks:

- Nothing is registered for controlling weeds, diseases and pests.

- Prices can drop sharply when the market is over-supplied.

- Buyers, brokers or contractors can be impossible to find.

The quinoa option

Dan Bolton, of Portage la Prairie, Man., is director of farm services for the Saskatoon-based Northern Quinoa Production Corporation (NQPC). Bolton has contracts for NorQuin quinoa from Selkirk in southeastern Manitoba to La Crête in northwestern Alberta.

NQPC is the oldest and largest of a few quinoa processors. It was incorporated in 1994 and is vertically integrated, from field to fork. It supplies the seed and buys back the crop.

”This year, we scaled back our acres and focused on a core group, but that’s not an indication of where we’re headed,” Bolton says.

“Last year, we had approximately 34,000 contract acres of NorQuin and grew more than we planned. We had between 130 and 140 growers (in 2017), who averaged 870 pounds per acre, clean,” he says.

Under contract, growers have seeded as little as 42 acres and more than 2,500 acres. Yields have ranged from less than 200 to more than 3,000 pounds per acre, according to Bolton.

On yield loss, two insects were the primary cause. They attack early and mid-season growth, while quinoa is looking like a vigorous crop of lamb’s-quarters.

“A stem-boring fly lays eggs inside the stem. The maggots will chew the interior of the stem, reducing the flow of nutrients and moisture during seed production,” Bolton says. “In good conditions, the plant can co-exist with that insect.”

The second is a moth, similar to diamondback.

“It has two life cycles. Larvae can chew the developing head and disrupt seed production. Later, it will eat dry seed. You can see big yield reductions there, too,” Bolton says.

At the moment, both insects are rare in Western Canada. They are specific to quinoa and don’t have a common name.

For the Prairies, it’s agreed that quinoa is a high-management crop and best management practice guidelines are being developed. Photos by John Dietz.

Quinoa is not a cereal, but a broadleaf plant that has a grain head that is broom-like, not unlike sorghum or millet.

BMPs in progress

Quinoa contains no gluten and is the only plant food that contains all the essential amino acids, trace elements and vitamins, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization. It is also highly adaptable and water efficient.

However, for the Prairies, it’s agreed that quinoa is a high-management crop. Best management practice guidelines are being developed.

Frey recently began co-ordinating quinoa research at the diversification centre in Roblin, Man., using NorQuin seed, with diversification centre sites elsewhere in the province at Roblin, Melita and Arborg.

“Quinoa is not a cereal. It’s a broadleaf plant that has a grain head that is broom-like, not unlike sorghum or millet,” Frey says.

“Quinoa has been grown in this region for a few years now,” Frey says. “Companies and individuals are working with it, in a fairly big way. The mandate of our centres is to look at crops that have potential in our climate. We try to find ways to grow them well and look at the potential of new varieties.”

Seeding rates appear to be seven to 10 pounds per acre for new growers, to reduce risk. Quinoa weighs 50 pounds per bushel – the same as canola. Timing for planting is being developed. An early stand can compete effectively against weeds, but needs to avoid hard frosts, Frey says.

“A good, clean seedbed is very important.”

Fertility requirements are roughly the same as wheat, for nitrogen and phosphorus. “A good, clean seedbed is very important,” Frey says. “This isn’t nailed down yet, but one thing it requires will be good weed management in the year before quinoa, and maintaining that up to the day of seeding through herbicides or tillage.”

Along with flies and moth pests, disease can break out in rainy conditions. The diversification centres hope to have recommendations for disease control coming soon.

For harvest, waiting for quinoa to dry naturally and then straight cutting at about eight to 10 inches above the ground seems to be working well. Combine settings are similar to barley.

“Given its small size, there’s less concern than you might think about being blown out the back. It’s heavier than you might think.”

At the Westman Agricultural Diversification Organization centre in Melita, Man., Scott Chalmers is in his second year of quinoa. “We had five varieties and it performed very well in 2017,” he says. “I was expecting a weedy experience, but it wasn’t that bad. It was quite competitive against our weeds. This year we have the variety trial and a seeding date trial.“

The crop development centres release reports annually of what they’ve learned, Frey says. Quinoa information, with all the rest, can be found online at mbdiversificationcentres.ca.

The spelt option

Seeding and harvest of spelt are the easy parts. In addition to a hefty seed price, spelt requires lots of storage space for long periods.

Most spelt is grown in Eastern Europe and Ukraine as fall-seeded cereal. In Germany, it is known as dinkel wheat or hulled wheat. It can be used as a feed grain alternative to oats and barley.

Ohio and Ontario are established production areas in North America, and the University of Saskatchewan has developed spring-planted spelt varieties for the Prairies.

On the Prairies, the spelt market at this point is much smaller than the quinoa market. It is mostly known as an organic grain and processed into flour. Consumers can find spelt products in health food stores and in a few supermarket aisles, and they are becoming popular at private artisan bakeries.

Spelt also is being promoted as a fall and winter cover crop by a few growers. For instance, seed producer Derek Axten, a southeastern Saskatchewan grower, is experimenting with using spelt for fall weed control and winter grazing.

Spelt is a true wheat, with lots of nutrition and with enough gluten for baking.

“Spelt looks like durum wheat all season and it’s treated like durum until harvest. Then it’s different.”

“Spelt looks like durum wheat all season and it’s treated like durum until harvest. Then it’s different,” Chalmers says. “Our sample bags filled right up as the seed does not actually thresh from the hull. Then we had to dehull the seed to get to the actual grain.”

Chalmers did demonstration trials with spelt in southwestern Manitoba for 2009, 2012 and 2013. Spelt can do very well in central and southwestern Saskatchewan, he says, where water is less abundant than in Manitoba and where Fusarium head blight risk can be lower.

Chalmers learned that spelt height and standability is similar to durum wheat. He fertilized it as he would durum wheat and applied herbicide in-crop to help it compete against wild oat and broadleaf weeds. He also used a fungicide to reduce Fusarium head blight.

Final yield potential was similar to spring wheat or bearded wheat.

“Organic growers really like spelt. It’s a very leafy crop and very competitive against weeds. But, conventional farmers have a difficult time with finding a market for spelt,” Chalmers says.

In the niche

In Manitoba, Larry and Pat Pollock have been supplying the organic spelt niche.

“We only grow spelt and don’t report our intentions for crop insurance,” Pat Pollock says. “We have 75 acres seeded this year and grow up to 90 acres.”

They have relied on spelt acres for most of their farm income for more than 10 years. They dehull and process all of their spelt for milling into flour. About 20 per cent is milled at home, stone-ground. They bag and deliver it to several bakeries in Western Canada as well as one in Thunder Bay.

The Pollocks have about 200 to 300 farm gate customers for the spelt grain, flakes and flour.

They also bag and sell spelt seed, supplying farms in Saskatchewan and Alberta.

“Ready for seeding, dehulled and cleaned, our price picked up at the farm is now $60 for a 50-pound bag. You want approximately two bushels to the acre when you’re seeding,” Pollock says.

If you risk the spelt production route, it’s a challenging road, she adds.

Seeding and harvest are the easy parts. In addition to a hefty seed price, it requires lots of storage space for long periods. Baking quality improves in storage for the first two years. After storage, when it’s aged, they remove the hulls, and then market to customers.

“It is tough and it is definitely a niche crop. It can be very profitable, once you have established your niche.”

“If you have organic spelt, you sell it by the bag, but not by the truckload,” Pollock says. “You pretty much have to do your own marketing. It is tough and it is definitely a niche crop. It can be very profitable, once you have established your niche. And, once you find a market, you ordinarily zip your lips about it.”

She recalls visiting an organic flour mill in British Columbia in about 2015. They wanted semi-loads of spelt weekly and offered to buy as much as Pollock would sell. Shortly after that, she says, “a huge glut of spelt was grown somewhere in the Ukraine area. They flooded the market and the price absolutely tanked.”

In Manitoba, Larry (pictured here) and Pat Pollock have been supplying the organic spelt niche to several bakeries and farm gate customers.

Bandwagon farming

For a choice between the two novelty crops, both the diversification specialists favor a small try at quinoa for the grower who has confidence about the weed control. An entry-level contract for NQPC is 50 acres.

Chalmers says, “Quinoa is gluten-free and that has become very popular. It’s becoming more of a staple, like rice. The yield was pretty decent for a broadleaf crop – without a hundred years of modern breeding – and there are about two processors right now who will take it by the truckload.”

By comparison, he says, the organic spelt market may be even more lucrative but it’s also very hard to get into that market.

On the other hand, the spelt market may just be undeveloped and need a ‘pioneer’ with vision to take it another direction. Options could include non-organic production for conventional bakeries and non-conventional uses, such as cover crops.

The risk with conventional spelt is significant.

Chalmers warns, “It’s easy for a lot of people to get on the bandwagon and flood the market.”