Features

Agronomy

Soybeans

Strip till in soybeans

Strip till offers several benefits to soybean growers on heavy residue stubble. A key benefit on sandy loam soils is leaving residue on the soil surface to protect against soil erosion by the wind – an occurrence in recent years after snow melts on tilled soils.

August 13, 2018 By Bruce Barker

Strip till left more crop residue on the soil surface compared to vertical till high disturbance. Strip till offers several benefits to soybean growers on heavy residue stubble.

Strip till left more crop residue on the soil surface compared to vertical till high disturbance. Strip till offers several benefits to soybean growers on heavy residue stubble.Reducing the amount of tillage passes to prepare the seedbed can also reduce input costs and save time, but questions arise regarding the impact on soil temperature, crop growth, maturity and yield. Patrick Walther, a graduate student at the University of Manitoba under the supervision of Yvonne Lawley, compared different tillage systems on corn stubble to see if strip till has a fit in Manitoba.

Walther conducted two years of research at the following sites in Manitoba: Winkler and MacGregor in 2015, and Haywood and MacGregor in 2016 on sandy loam soils. He compared double disc, high disturbance vertical tillage (six degree angle on disc), low disturbance vertical tillage (zero-degree angle on disc) and strip till implemented in the spring or fall. Soil temperature was measured at five and 30 centimetres deep, and soybean growth, maturity and yield was observed. Soybeans were planted on 30-inch row spacing using a planter with disc openers and no trash cleaners.

Soil temperature and emergence

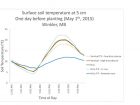

Walther first looked at soil temperatures. An example of the differences between tillage treatments is shown one day before planting on May 1, 2015, in Winkler. High disturbance disc and vertical tillage treatments followed fairly similar paths as the soil warmed up during the day and cooled off at night.

“Interestingly, strip till had lower night time temperatures and higher day time temperatures,” Walther says.

Walther says there may be several reasons for the difference in strip till temperatures. The first is that strip till pushes trash to the side so that the residue is not acting as an insulator. The bermed soil left by strip till has greater black soil surface area exposed than flat soil, promoting more warming and cooling. The berm is also fluffier than tilled soil, with more air pores that warm up and cool down faster.

Although differences in soil temperature were observed on an hourly basis on individual days, the impact of these temperature differences need to be considered over time to understand their impact on an emerging plant says Walther. Hourly temperature above 10 C (base temperature for soybean) was added up for the first ten days after planting. This accumulated temperature effect revealed no significant temperature differences in the seedrow among treatments at any site-year. This explains why there were few differences in emergence for the soybean test crop he says.

Soybean growth

While soil temperatures are interesting, emergence, crop growth and yield pay the bills. In three out of four site years, Walther did not find any statistical difference in emergence between the tillage treatments. At the fourth site, strip till lagged behind in emergence but the final plant stand ended up being the same at 30 days after planting.

“Soybeans are good liars early in the season anyway. What is much more important is plant growth at flowering and pod stages, which is where you make the yield,” Walther says.

Days to flowering and percentage flowering were different between 2015 and 2016. In 2015, days to flowering and percentage flowering were very similar among tillage treatments. In 2016, disc treatments were slower to flower. For example, in MacGregor in 2016, the disc treatment was about 30 per cent flowering at 47 days after planting but strip till was over 75 per cent in flower.

Statistically, strip till soybeans grew the tallest, but only two cm taller, so not agronomically very important. Pod height had highly significant differences, but again, not that agronomically important. Measured from the bottom tip of the lowest pod to the soil surface, strip till was 60 millimetres (2.4 inches) compared to 65 millimetres (2.6 inches) for double disc and high disturbance vertical till, and 69 millimetres (2.7 inches) for low disturbance vertical till. So, still achievable for floating cutterbars on a combine.

There were no statistically significant differences in pods per plant. As a result, for the four site years of research, no significant differences in grain yield were observed.

The only yield-related difference was with grain moisture. Strip till soybeans had significantly lower grain moisture content of 13.38 per cent compared to double disc at 14.29 per cent.

“The residue management treatments in this experiment were dramatically different and we were expecting large differences in yield, but what ended up happening, with no differences in yield, was unexpected,” Lawley says. “This is good news because it means there are a variety of approaches – including strip till – that will work for farmers to manage corn residue before soybeans.”

Walther also looked at yield monitor data to see if there were differences in yield variability across fields depending on tillage treatments. He found that all tillage treatments had similar yield across the field, indicating all tillage treatments had similar consistency across field variability.

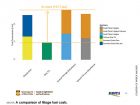

Strip tillage more economical

Walther partnered with Prairie Agricultural Machinery Institute (PAMI) to look at tillage costs in the different tillage systems. They identified a major advantage in strip till, which used three times less fuel compared to double disc. Strip till only required one tillage pass, either fall or spring, compared to two passes for the other high disturbance tillage systems. As an example, if you consider an average farm in Manitoba of 1,134 acres, if the whole farm were planted to corn, managing the corn residue with strip till would save a farmer up to 3.7 days compared to double disc.

“Farmers say I don’t care so much about fuel but my time is important. Eliminating one tillage pass was an additional major benefit,” Walther says.

Walther says the results of the research show that strip till on sandy soils look promising for soybean growers. A strip till system could bring major time, input and soil conservation benefits. Typically conducted in the fall, a strip till could also include phosphate (P) fertilizer applications that would allow farmers to meet the high P demands of soybeans without having to just rely on soil or starter P.

Strip-till soybeans on the U.S. Northern Great Plains

Research in Minnesota has found similar results for soil temperature, growth and yield when soybeans are grown with strip till systems. University of Minnesota research from 2010 through 2012 compared chisel plowing with spring field cultivation, disc ripping with spring field cultivation, fall strip tillage and two passes with a shallow vertical tillage implement. Yields between the tillage treatments were not statistically different.

In a separate three-year study during 2006 to 2008 in southern Minnesota, researchers compared soybean yields among chisel plowing, strip tillage and no-till for fields previously planted in strip-tilled corn. The type of tillage had no effect on the soybean yields during the three years.

A new four-year study was implemented in 2015 by North Dakota State University and University of Minnesota. This multi-state effort is in year three of a six-year field study. Four on-farm locations are under a corn-soybean rotation and rotate each year. At each location, the four tillage practices are demonstrated using full-sized equipment in plots of 40 or 66 feet wide by 1,800 feet long in a replicated design. At each site, a chisel plow, vertical tillage, strip till with shank, and strip till with coulter systems are demonstrated

The soil types at the four sites included Fargo silty clay, Lakepark clay loam, Barnes-Buse loams, Delamere fine sandy loam, and Wyndmere fine sandy loam. These soils cover over 67 million acres of farmland in the Northern Great Plains regions.

During the spring of 2016, soil temperatures and water contents did not tend to differ among tillage practices except for a brief period of approximately seven to 10 days immediately following soil thaw in early March. This was primarily due to the dry spring conditions and relatively low soil water contents. These differences would likely persist for longer periods as spring precipitation increases. Soybean yields in 2015 and 2016 did not significantly differ among tillage treatments.