Features

Agronomy

Cereals

Selecting high yield cereal varieties

With the removal of kernel visual distinguishability (KVD), and the establishment of the new general purpose (GP) wheat class, marketing and cultivar development is already changing significantly.

February 24, 2010 By Bruce Barker

|

|

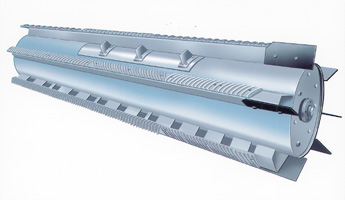

| The Western Canada Ethanol Feedstock Trial is trying to determine the best varieties for ethanol production. Photo courtesy of the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture.

|

With the removal of kernel visual distinguishability (KVD), and the establishment of the new general purpose (GP) wheat class, marketing and cultivar development is already changing significantly. That means more choice and opportunity for farmers wanting to grow cereal varieties outside of the traditional high-protein bread wheat or durum market. “Producers now have to ask themselves, ‘what is your market?’” says Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) cereal agronomist Brian Beres at Lethbridge, Alberta. “When talking high yield varieties, producers need to step back and decide what they want to accomplish.”

Most plant breeders would agree that the strict adherence to milling wheat standards came with a genetic yield drag. With KVD gone, new varieties are already hitting the market. For example, CDC Ptarmigan is a soft white winter wheat that was previously unregistered because of quality and KVD concerns, but with the removal of KVD and the establishment of the new GP class, it was registered as a GP wheat and is now available for use as a livestock feed or as an ethanol feedstock.

Variety selection balances yield and stability

Once the decision to grow for the GP feed or ethanol market has been made, Beres says there are still a lot of decisions to make regarding variety selection. With several classes of wheat and even triticale providing high yielding genetics, he says that looking at yield and starch production are important considerations for producers. Classes of wheat high in starch, such as the soft white spring wheat class, have very high yield potential and lower protein.

With CWRS bread wheat varieties ruled out of the ethanol market because of lower yields and higher protein, producers can choose from soft white spring wheat (CWSWS), Canada Prairie Spring Red (CPSR), the GP class and possibly triticale. To help assess the potential of different wheat varieties for ethanol use, a Saskatchewan study, the Western Canada Ethanol Feedstock Trial, was initiated in 2005 by the Western Applied Research Corporation at Scott, Saskatchewan. As other sites became interested the project expanded across Western Canada in 2006 and 2007 and then amalgamated in 2008 with an AAFC project to include a total of 25 sites across Canada. Dr. Curtis Pozniak, wheat breeder from the Crop Development Centre at the University of Saskatchewan, and Beres from AAFC Lethbridge, were instrumental in co-ordinating and guiding the project. “We have developed a lot of data and the analysis and final reports are still in progress, but the trends we have seen are fairly consistent across the board over the years and the different sites,” explains Sherrilyn Phelps, a regional crop specialist with the Ministry of Agriculture at North Battleford, Saskatchewan. “One of the questions that we wanted to answer was whether the soft white spring wheats would maintain their high yield under dryland conditions. They were initially bred and grown under irrigation, so we were concerned that they wouldn’t yield as well and would have higher protein content under dryland production. That wasn’t the case.”

At more than 15 of the locations in Western Canada, the highest yielding were the soft white spring wheats (CWSWS) with AC Sadash and AC Andrew the highest yielding varieties (Table 1).

|

Triticale may be of interest for ethanol production or other biorefinery applications as it is a high yielding cereal that has large seeds with high starch content and low protein accumulation. The perceived limitation for production is later maturity and susceptibility to ergot, but Beres points out that crop maturity of triticale parallels soft white spring wheat and is even preferred when compared to soft white spring in the shorter season environments. He adds that ergot susceptibility has improved with the newer cultivars. The advantage of height is the increase is straw production, which could be a source of biomass, whether for ethanol or other forms of energy.

Phelps says that in her experience, the soft white winter wheat varieties do yield well and are a good option in winter wheat producing areas. However, in some parts of Saskatchewan, winter wheat has not performed consistently due to dry conditions or winterkill. From her viewpoint, in these areas a producer would be better off growing a soft white spring wheat variety that is a few days later than a variety like AC Superb (hard red spring) than to risk a poor soft white winter wheat stand.

Winter cereal can outcompete weeds

A recent study by Beres indicates that winter cereals have greater weed competitive ability and higher grain yield but successful stand establishment in fall is critical. Future studies of winter wheat will target the improvement of stand establishment. “Even though soft white spring wheat is few days later than AC Barrie, it is not that much different than Superb (a high yielding HRS). In areas where Superb can be grown successfully, producers can grow soft white spring varieties, especially the varieties Sadash and Bhishaj that are similar in maturity to Superb. AC Andrew is two days later. Seeding early is key for those longer season varieties.

The advantage to cereals for ethanol is that light frost does not downgrade the grain to the same extent as hard red spring wheat,” says Phelps.

Beres notes that for ethanol production soft white spring wheats have become the standard, and that most acres of soft wheat are now located in dryland regions of Saskatchewan, instead of the traditional irrigation belt of southern Alberta. The soft white spring varieties Bhishaj and Sadash, and the triticale variety AC Ultima produced the highest overall starch content. CDC Ptarmigan soft white winter wheat was not in the study but produced significantly lower protein and higher grain than the milling variety Radiant in an integrated nutrient management study headed by Beres. “If you are looking for that 20 percent yield advantage, soft white spring wheat and some of the spring triticales can get you there,” explains Beres. “There are some new GP varieties, but the only variety with a high yield advantage over conventional classes of wheat to date is the winter wheat variety CDC Ptarmigan. So, a shift from spring wheat to winter wheat is another way to quickly improve on-farm yield potential by 15 to 20 percent.”

For triticale, though, processing quality may be an issue. Growers are advised to contact their grain buyers to ensure they have a market if grown for ethanol. At Pound-Maker, an integrated feedlot and ethanol facility at Lanigan, Saskatchewan, ethanol plant manager Keith Rueve says they are conducting trials on triticale to see if it fits into their production process. They grew 160 acres of triticale during 2009, but due to the late harvest, it was first combined in mid-November. He is hoping he can get it dried down so they can run several test batches.

“The challenge with triticale, and to some extent rye, is with viscosity. We use an enzyme specific to wheat, and when we change grains, we may need to run with a different enzyme package to reduce the viscosity,” explains Rueve. “We had very high triticale yields, but it just matured later than we would have liked.”

Yield stability important

A second part of the variety selection puzzle is yield stability. Depending on a producer’s risk tolerance, selecting a variety that has high, stable grain yield year-after-year is likely a better decision than selecting a variety that performs great one year, and poorly in another.

Beres conducted two studies to assess the yield stability of high yielding wheat. He found that the soft white spring variety AC Reed was highly stable across all the sites, including dryland conditions that were the driest on record. Another soft white spring variety, AC Nanda, was less stable likely due to its later maturity. “Preliminary data from the ethanol study suggests the newest soft white spring wheat variety Sadash is very similar to AC Reed, while AC Andrew may have similar stability as AC Nanda,” explains Beres.

Looking forward, the increased demand for high yield, high starch content varieties will likely lead to greater adoption of soft white spring wheat, and possibly a shift to high yield spring and winter cereals like triticale.