Features

Agronomy

Seeding/Planting

Studying row spacing effects

Row spacing for various field crops on the Prairies, particularly in no-till and higher residue cropping systems, continues to be a big area of focus for researchers and growers. Understanding how wide is reasonable, what the benefits and drawbacks are and associated risks remain top priorities.

March 26, 2017 By Donna Fleury

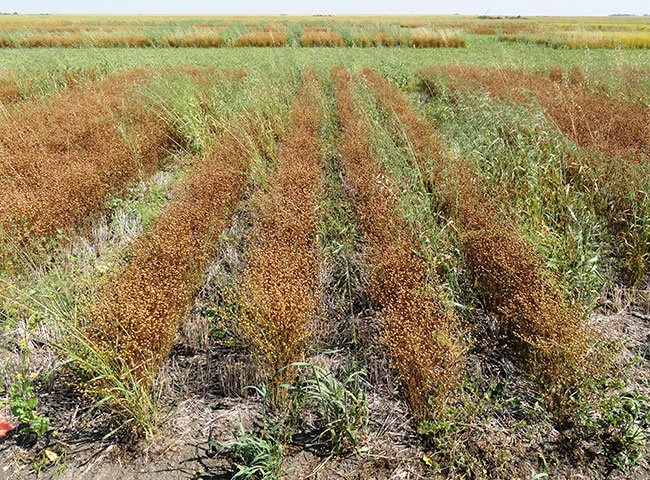

Flax Row spacing for various field crops on the Prairies

Flax Row spacing for various field crops on the PrairiesFor the past several years, researchers at the Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation (IHARF) and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Indian Head, Sask., have been conducting row spacing research with a variety of crop types. “We recognize that one solution to improved residue management is to increase row spacing, but there are limits as to the extent to which this can be done without compromising yield,” explains Chris Holzapfel, IHARF research manager. “Most research shows that spacing of at least 12 inches is possible without reducing yield for most crops; however, results can vary depending on crop management and environmental conditions.”

Although it is commonly accepted that narrow row spacing gives the greatest potential grain yields for the majority of crops under most circumstances, there are some advantages to wider row spacing that should be considered, along with productivity and yield. Holzapfel notes some of the benefits of wider row spacing: potentially lower initial equipment costs at any given width, reduced maintenance on that equipment, and fewer moving parts and tips to wear out. Growers can also typically get away with less horsepower to pull drills when they have wider row spacing throughout the field, burning less fuel on a per acre basis and speeding up the seeding operation. Slight increases in row spacing can eliminate some of the challenges of seeding into heavy residue with no-till, and, although there may be a slight yield reduction every few years (depending on conditions), this may be something that some growers are willing to live with.

“Since 2011, we have been conducting research on various crops using different row spacing treatments combined with other factors, such as side-banded [nitrogen] N rate, seeding rate, weed control and fungicide applications,” Holzapfel says. “Optimal seeding and fertility rates don’t change too much with row spacing, with a few exceptions. With side-banding of N fertilizer, the N concentration in each band gets more concentrated as the row spacing gets wider.” For example, 100 pounds per acre (lbs/ac) of N is much more concentrated on 15-inch row spacing than on 10-inch rows. Inadequate separation of N from the seed for any reason could have a higher potential for seeding damage.

In terms of seeding rates, Holzapfel cautions growers to consider suboptimal rates when working on wider row spacings. Using recommended rates can address potential risks of poor germination or low plant stands due to weather conditions, frost, flea beetles, seedling diseases or other factors. A few more plants can also fill in the canopy a bit more quickly and aggressively in the growing season. That said, there is no reason to get aggressive with seeding rates in an attempt to compensate for the increased mortality often seen with wider row spacing. The maximum achievable plant populations tend to be reached at slightly lower seeding rates.

“The research is at various stages – however, crop types vary in their ability to compensate for wider row spacing,” Holzapfel says. “Our research work so far indicates that flax is the most sensitive to wider row spacing, followed by wheat, oats and soybeans, with canola being the least sensitive. Research is still required on pea, lentil, fababean and other cereals.”

Row spacing research so far

In 2009 the first row spacing project was started by Guy Lafond, a researcher with AAFC. Oats grown in row widths of 10, 12, 14 and 16 inches, using five rates of N fertilizer, were investigated for three years. The objective was to study the interaction between row spacing and N rate in oat on various factors under a no-till production system. The results showed plant density was not affected by N rate and there was no N rate by row spacing interaction. Grain yield was similar among 10-, 12- and 14-inch row spacings, but there was a 13 per cent yield decrease at 16 inches. The results support the feasibility of wide row spacing up to 14 inches, combined with placement of all fertilizer requirements in a side-banded position.

In 2012, Holzapfel initiated a four-year project at Indian Head to evaluate canola performance in wider row spacings of up to 24 inches. Three separate field trials were designed to evaluate various treatments, including: row spacings of 10, 12, 14, 16 and 24 inches; side-banded N fertilizer rates of zero, 50, 100 and 150 kilograms N per hectare; seeding rates of 30, 60, 90 and 120 seeds per square metre; and no in-crop herbicide versus in-crop herbicide applications. “Generally, canola emergence declined as row spacing was increased, but [declines] were minimal or non-significant. Although in some cases yields were higher at the 10-inch row spacing, in two of three years canola yields at 24 inches were also amongst the highest,” Holzapfel says.

Wider row spacing in canola also resulted in slight but significant delays in flowering and maturity. However, the effects were generally much smaller than those caused by either N fertilizer or seeding rate when adequate seeding rates are used. The results also suggest seeding rates should not be reduced below typically recommended rates as row spacing is increased. However, at the same time, there was no benefit to using aggressive seeding rates (for example, greater than 90 seeds per square metre) combined with very wide row spacing (such as 24 inches). The study did not show any practical, short-term effects of row spacing on weed control that could not be managed with well-timed herbicide applications. With that in mind, row spacing effects on weed control put more pressure on herbicides and may be of much greater importance when dealing with hard to kill or herbicide-resistant weeds.

Flax field trials were conducted at Indian Head from 2014 to 2016, with treatments including a combination of five row-spacings (10 to 24 inches) and two fungicide levels (treated versus untreated). “We are still waiting on the third year of data, but flax yields did decline with increasing row spacing in both years – more prominently in 2015,” Holzapfel says. “Yield losses in 2015 averaged about five per cent between 10-inch and 14-inch row spacing, and were a bit less in 2014. From a practical sense, growers with row spacing wider than 12 inches can still seed flax with minimal yield losses; however, with all other factors being equal, lower mean yields or increased yield variability may occur as row spacing is increased. We also did not detect a response to fungicide treatments in either year, although this may vary when disease pressure is higher.”

In 2014, a four-year soybean project was initiated at Indian Head to refine row spacing recommendations for short season soybean varieties at varying seeding rates. The study combined five row spacing levels (10, 12, 14, 16 and 24 inches) and three seeding rates. Holzapfel says early indications point to soybeans being well suited to wider row spacings. “Yields were similar at all spacings in 2014. However, in 2015, yields were significantly higher at 10- and 12-inch spacing and then levelled off from 14 up to 24 inches, although losses weren’t high. We’re not sure why, but are wondering if variety could be a factor, as some are more capable of branching out and filling in the canopy, while others can be very upright, non-branching varieties. It is possible that some very early maturing varieties that are well adapted to Saskatchewan may be less well adapted to wider row spacing than more traditional varieties. This is something we want to look at further,” Holzapfel says. Final results will be available at the end of 2017.

“These research projects that are completed or underway so far show that wider row spacing is possible for many of our crops, and some growers have indicated good success in their cropping systems,” Holzapfel says. “The most common row spacing continues to be nine inches to 12 inches, but a few growers are using up to 15-inch commercial drills. In some cases, sound agronomic management – including timely and thorough weed removal – is more critical with wider row spacing. Any delays in maturity caused by wider row spacing are typically minor and less than those caused by increased fertility or reduced plant populations. While yield variability increased with wider row spacing, this may be offset by reduced equipment cost, fuel consumption and horsepower requirements [per acre].”

Holzapfel says other potential benefits may include reduced seedbed preparation requirements (i.e. easier to seed through heavy residue), water conservation associated with less soil disturbance (which would be more valuable in semi-arid regions) and an improved ability to seed between the previous year’s stubble rows.

Growers will have to determine what works best in their cropping system, and whether or not the benefits of wider row spacings outweigh the potential risks of yield variability. Meanwhile, research is continuing into wider row spacing for other crops to help growers maximize yields and optimize cropping systems.