Features

Agronomy

Plant Breeding

Seed Chipper lets breeders take a peek at a seed’s DNA

Many farmers are familiar with the results of Monsanto’s research like its Roundup Ready technology.

April 2, 2010 By Carolyn King

Many farmers are familiar with the results of Monsanto’s research like its Roundup Ready technology. At the 2009 Outdoor Farm Show at Woodstock, Ontario, farmers had the chance to see a different aspect of the company’s research and development, an ingenious device called the Seed Chipper. “The Seed Chipper was entirely created, innovated and developed internally at Monsanto,” says Dr. Mark Lawton, Monsanto’s technology development lead for Eastern Canada. “This tool enables us to peek inside a seed to get the DNA information, so we can use that information as part of our selection process to determine the best seeds to keep versus seeds not to keep.”

|

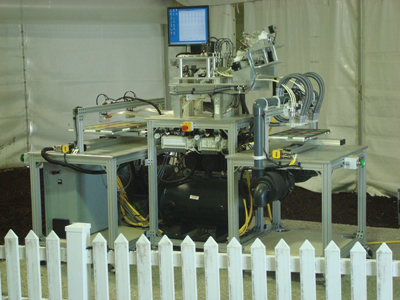

| The Seed Chipper rapidly and accurately slices a tiny chip off of an individual seed. The chip then goes for DNA analysis and the seed is still viable so it can be grown in breeding trials.

Photo courtesy of Monsanto.

Advertisement

|

He notes, “Traditional breeding is a numbers game. Historically breeders would look at a few thousand lines a year. Using the information from their plots, including agronomic observations during the year, yield information at harvest, their experience from year to year, they would make selections on which seeds to keep for the next year’s plots and which seeds to throw away.”

Knowing a seed’s DNA fingerprint improves the odds in that numbers game.

A chip off the same seed

“Normally in our breeding programs we would look at the DNA of the leaf sample, which meant you had to take the seeds, plant them out in a nursery or greenhouse, let them grow up to a certain size, and then take a leaf sample and run the DNA analysis,” explains Dr. Cindy Ludwig, one of Monsanto’s US-based engineers who helped develop the Seed Chipper. “That involves a lot of space, a lot of resources, so the idea came up that, if we could test the seeds before we plant them, then we could save all that time and resources by only planting the seeds that were going to move forward in

the breeding program based on the DNA analysis.”

With that goal, automation engineers at Monsanto’s St. Louis research facility set about exploring the idea. They worked closely with the people in the DNA lab because doing DNA fingerprint analysis on leaf tissue is a little different than doing it on seed tissue. “We figured out how much material they needed to do a good DNA analysis, and how much material we could take off the seed without damaging the seed so it could still grow, because the whole point was to grow that same seed that we tested,” says Ludwig.

They wanted to grow the tested seeds because the DNA of each individual seed is a little different from the DNA of every other seed in the same seed head, cob or pod. She says, “It is almost like puppies in a litter, even though they have the same parents, they can all be slightly different.”

The researchers determined that five milligrams would be the optimal size of the seed tissue sample for DNA analysis. And they worked out by hand the step-by-step process to cut a five-milligram chip off the seed, being especially careful to avoid the embryo area; if the embryo is damaged, the seed will not grow. Then Monsanto’s mechanical engineers developed a machine to replicate that chipping process.

Ludwig says, “Within a few years we had developed a machine that would singulate (pick up one seed at a time), position the seed in the cutting area so we could take a chip off the seed in the right spot, and then run the chip broach over the seed and remove that material.”

To date Monsanto has created two versions of the Seed Chipper, one for corn and one for soybeans. Lawton explains, “Each crop presents unique challenges. Corn, for example, was interesting because when corn gets singulated it never sits the right way to be cut. So there has to be an extra step in the process where an image is taken of the orientation. Based on that image there’s a physical adjustment to position the embryo away from the area that will be chipped, ensuring the seed is precisely located so you get enough of a chip for your DNA information but it’s small enough and in the right spot so the seed will still germinate.”

Linking the components

The Seed Chipper is one component in a rapid, accurate system. The Chipper can chip about one seed per second. Once a chip is cut from a seed, a blast of air blows the chip to one side and the seed to the other side. A bar coding system is used so the chip’s DNA results can be automatically linked to the correct seed.

|

| Wheat is one of the other crops that Seed Chippers are being developed to test, as well as cotton and various vegetables.

Photo by Ralph Pearce.

|

Next, the chip goes to another automated system developed by Monsanto that analyzes the chip’s DNA. The high-throughput genotyping lab analyzes millions of samples a year using the fastest available robots and cutting-edge automation technology.

Then the DNA information is uploaded into a computerized data analysis system that uses Monsanto’s molecular marker database to predict how the seed will perform agronomically. Molecular markers are regions of DNA associated with specific characteristics, like high yield, disease resistance or good standability. In the course of its research during many years, Monsanto has developed a large library of molecular markers.

While the DNA work is going on, the seed is sent to an automated storage system that can retrieve the seed when the breeders want it.

This interlinked system means Monsanto breeders can go online, look at the DNA results of seeds from their own trials as well as from other Monsanto trials around the world, and place an online order for the particular seeds with the DNA patterns that the breeders think would be best for their own region. Within a day, the automated storage system can retrieve the selected seeds from the storage racks, put the seeds in an envelope, and ship the envelope to the breeder. “I think the biggest challenge was getting the different sciences and different departments to all work together to develop the entire platform because one system won’t stand alone. It really has to be integrated throughout the breeding, the chipping and the DNA analysis,” notes Ludwig. She says breeders, engineers and computer programmers all worked together to create a seamless system. “Monsanto is really unique in that we have all these different departments with their specialty.” This in-house capacity is due to Monsanto’s research and development investment, which now exceeds $1 billion annually.

Advancing breeding

The Seed Chipper has quickly become a normal part of Monsanto’s corn and soybean breeding process.

Lawton notes, “Tools like the Seed Chipper allow us to use the knowledge we have gained with these genetic markers that we have studied and developed over time and apply that knowledge in real time. So at the harvest we can get the seeds chipped, fingerprinted and before the breeders go back and plant the seed again in the next season, which can sometimes be just a couple of weeks away if the breeders are doing contra-season grow-outs, they’ll have that information from the seed chip to make the very best selections on what goes forward, and more importantly, what is not continued.”

One of the first uses of the Seed Chipper was in developing the Genuity Roundup Ready 2 Yield soybean. Ludwig says development of this soybean involved changing the location of the Roundup Ready gene. “Instead of inserting it in one area of the DNA, we inserted it into a different area that is associated with a high yield. Then we used the Seed Chipper to bring that product forward, and because of the efficiency of testing the seeds before we planted them and the amount of nursery that we could utilize for the right seed and not the wrong seed, we were able to bring that product to market about two years faster,” says Lawton. “That is a great benefit for farmers because now they have an extra two years of having a high yielding soybean in their fields.”

Monsanto now has fleets of Seed Chippers to help its corn and soybean breeders. And the company is developing Seed Chippers for some of Monsanto’s other core crops, including cotton, wheat and vegetables. Lawton says, “The ultimate goal is to have the best germplasm with the best traits and that’s the best recipe for success for any producer.”