Features

Agronomy

Diseases

Researchers tracking clubroot spread

During the past several years, clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae) has been in the news because of its devastating impact on canola production in Central Alberta. There is good and bad news here.

October 20, 2009 By Bruce Barker

During the past several years, clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae) has been in the news because of its devastating impact on canola production in Central Alberta. There is good and bad news here. The bad news is that clubroot has been identified in a Saskatchewan soil sample in 2009, and preliminary computer modeling shows that the clubroot pathogen may be able to infect canola across the Prairies.

|

|

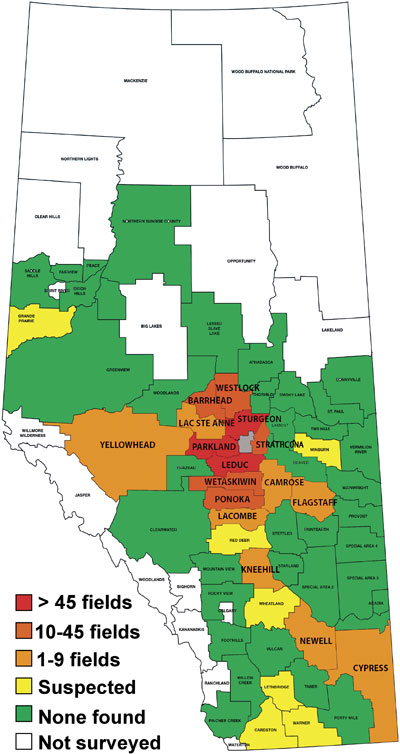

| Clubroot status, September 2009 Map Courtesy of Strelkov et al., University of Alberta. |

The good news is that a huge research effort is underway to better understand and control the disease, and that a new clubroot-resistant variety has been registered already for commercial use by Pioneer Hi-Bred, with another one from Monsanto expected to be available for planting in 2010.

Clubroot has affected cruciferous crops worldwide. In Alberta, the epicenter for clubroot on canola in Western

Canada, 16 municipalities and the city of Edmonton have confirmed cases of the disease, with another seven counties having suspected cases by the end of September 2009. According to information provided by Stephen Strelkov and colleagues at the University of Alberta, clubroot has been detected in approximately 452 fields since 2005, with incidence levels ranging from below 30 percent (low) to above 70 percent (high). The disease distribution in infested fields has generally been patchy, but in the 10 to 15 percent of canola crops with high levels of clubroot infestation, the disease has occurred fairly evenly throughout the field.

In 2008, approximately 160 new fields were confirmed through survey work by the University of Alberta, Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development, and Agricultural Service Boards. Surveys also were conducted in 2009, and the results will be available during the winter of 2009/10.

Ron Howard, a plant pathologist with Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development (AARD) at Brooks, Alberta, says that clubroot detections continue to rise in Alberta, and that the annual clubroot disease survey is working to, not only confirm locations where clubroot is found, but also to help scientists understand the environmental conditions that favour disease development, and the mechanisms by which clubroot spores can spread over long and short distances. “It is possible that the clubroot pathogen has existed in the soil for years, but at low levels that did not cause an economic impact on canola. It could have been there in the soil until conditions became right, such as a change in environmental conditions and tightening canola rotations,” explains Howard.

|

|

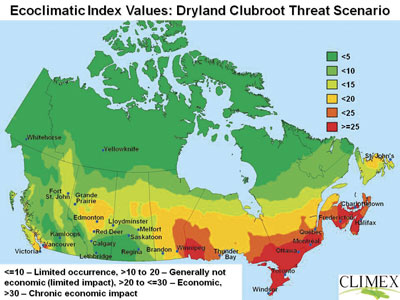

| Climex modelling shows the potential for clubroot infestations. Map courtesy of Turkington, Olfert and Weiss, AAFC. |

|

|

|

| Growers need to keep scouting their fields and looking for symptoms. Photo by Bruce Barker. |

|

|

|

| A canola root with a severe clubroot infection. Photo Courtesy of Kelly Turkington, AAFC. |

In Manitoba, reports of the presence of the pathogen responsible for clubroot have been seen on some cruciferous vegetables. The first presence dates back to an unconfirmed report on rutabaga in 1925. In the 1980s, clubroot was found on market garden cruciferous vegetables.

Anastasia Kubinec, provincial oilseeds specialist with Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Initiatives (MAFRI) says the only detection of clubroot on Manitoba canola occurred in 2005. The occurrence was of very low incidence, and the symptoms were of very low severity.

Reports from disease surveys of canola in Manitoba, which were not targeted at clubroot, have not detected any plants with symptoms of clubroot in canola production areas. In 2009, as part of the disease survey, 150 canola fields were visually surveyed for clubroot, and another 60 fields were soil sampled for detection of the clubroot pathogen. “Our recommendation to producers is to keep scouting their fields and watch for symptoms. If something is puzzling, go pull up the plants and see what they have,” says Kubinec.

In Saskatchewan, Faye Dokken, provincial plant disease specialists with the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture, says that clubroot symptoms have not been observed on any of the canola crops surveyed in Saskatchewan disease surveys. However, she does confirm that, in 2008, the clubroot pathogen’s DNA was detected in a soil sample collected from one of 30 randomly selected fields in the survey.

A second sample was obtained from the same field in west-central Saskatchewan, and the DNA diagnostic test was again positive, with small galls developing in the bioassay test. “The tests indicate that there is viable inoculum in the soil, but the inoculum levels appear very low,” says Dokken. “It’s impossible to say where the inoculum came from, but we will continue to monitor the disease.”

In 2009, 130 fields were visually surveyed in Saskatchewan with 60 soil samples taken. Results will be available later during the fall or winter. Meanwhile, in order to help farmers battle the disease, clubroot was declared a pest under The Pest Control Act in Saskatchewan in June 2009, joining Alberta, which made clubroot a “pest” several years earlier. Under The Pest Control Act, people who own, occupy or control land are required to take measures to destroy, control and prevent the spread of pests. “The focus is on education and prevention. We have a Saskatchewan Clubroot Management Plan, which continues to provide information for public awareness and contribute to disease surveillance in Saskatchewan,” says Dokken.

Computer modelling may show potential spread

Kelly Turkington, a plant pathologist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lacombe, Alberta, has been collaborating with colleagues Owen Olfert and Ross Weiss at AAFC Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, to help assess the potential distribution of clubroot in Canada. They have been using the computer simulation program Climex to model potential clubroot distribution and severity based on climatic parameters such as temperature and moisture.

“The model makes the assumption that the pathogen is already there. With the model, our focus is on growing season development. We are focusing on temperature and soil moisture, the two primary factors for plant disease,” explains Turkington. “In our initial work with Climex, we found that areas in central Alberta, along with much of Manitoba were at greater risk, with the Red River Valley and the Edmonton region showing the highest risk.”

“The wetter areas are the ones at greatest risk. In dry-land areas, the potential threat appears to be lower, but the exception may be in irrigated areas, where the risk could be high as well,” says Turkington.

They also ran the model based on a 30 percent increase in summer rainfall. Under that scenario, much of the Grey Wooded, Black and Dark Brown soil zones were at high risk of chronic economic impact due to clubroot.

Another risk factor is soil pH. Areas with low soil pH have the greatest risk, and large areas of central Alberta and the Peace Region have acidic soils (pH less than 7). Turkington indicates that they are working to include pH in the CLIMEX modelling. “In general, the more acidic soils are more at risk, but that’s not an absolute,” says Turkington. For example, Alberta surveys conducted by Strelkov at the University of Alberta have indicated that the disease can also develop under alkaline soil conditions.

In addition, some preliminary research conducted by Turkington and colleagues from AAFC Saskatoon has looked at wind trajectories to see how wind moving from high risk locations might distribute soil particles. The theory is that wind may carry soil particles containing resting spores of the clubroot pathogen to other areas of the Prairies. They found the occurrence of wind trajectories that may potentially spread dust from west to east, but more research is needed.