Features

Agronomy

Cereals

Ramping up wheat yields on the Prairies

How can Prairie growers ramp up spring wheat yields? Sometimes a view from outside can offer a fresh perspective.

Research done by a cereals specialist in Ontario offers some possibilities.

“I’m suggesting some things that western growers could try and see if they could push wheat yields the way we’ve been able to in Ontario,” says Peter Johnson, provincial cereals specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), and a farmer himself in southwestern Ontario.

“I am by no means an expert on western Canadian wheat production, but I have some ideas that work for us in Ontario, that work in Europe, in New Zealand, all over the world. You would expect they could work in Western Canada too.”

Nitrogen plus fungicide synergy

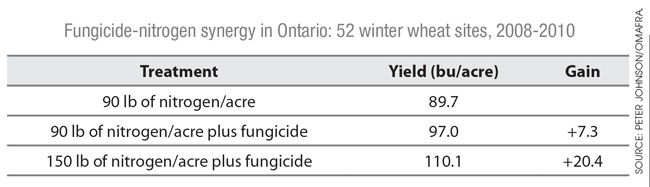

In Johnson’s opinion, the most exciting opportunity for major wheat yield increases is through the interaction between foliar fungicides and nitrogen. From the many Ontario field trials he’s done over the years, Johnson knew that nitrogen applications alone improve wheat yields, and that fungicide applications alone improve yields. The surprise came when the Ontario researcher examined the effects of the two practices together.

“Using the two practices together, we have astounding yield increases between 16 and 20 percent,” he notes. “Typically, with other practices, we might get a one to three percent yield increase, minor increases that add up over time. To gain a 20 percent yield boost in one step is absolutely unheard of in crop production. There’s a synergy between nitrogen and fungicide, so when you use the two together it’s really one plus one equals three.”

He explains the reason for that synergy: “Nitrogen drives crop yields, and in wheat it drives yields additionally because wheat is a high-protein crop and protein requires nitrogen. So wheat is incredibly responsive to nitrogen,” he says. “However, when you apply nitrogen by itself, you build a big, thick canopy, and because it’s so lush and humid in the canopy, disease can go wild. It can wipe out all the green tissue, so that tissue is not available for the grain fill process.

But when you also apply a fungicide, you keep the plant alive and healthy enough to utilize the added nitrogen [for grain filling].”

Johnson suggests western growers could start off by trying 30 lb/acre of added nitrogen and one late application of a foliar fungicide. “The fungicide should be applied as late as the grower is willing to apply it, up to five days after heading. We see much less response to fungicides applied to wheat between the five-leaf stage and growth stage 30, the beginning of stem elongation. I prefer the head timing, but not everybody is willing to go quite that late.”

Frost seeding

Another intriguing idea to boost spring wheat yields is frost seeding. Also called dormant seeding, this practice involves very early planting before conditions allow the crop to germinate. Johnson has seen spring wheat yields increase by as much as 40 percent in some years in Ontario with frost seeding. The yield advantage of frost seeding tends to be higher the more that regular spring seeding is delayed by spring weather conditions.

In Ontario, frost seeding is usually done when there is little or no snow, the frost has come out of the ground, and the night time temperature is between -2 and -7 C. “With those night temperatures, we get just enough frost in the soil surface that it will carry my seeding equipment,” says Johnson. “I use no-till seeding equipment that has the force to push through that layer of frost and drop the seed into the ground between a half-inch and an inch deep. I don’t worry about closing the slot because when the frost comes out in the morning, the soil will fall in on top of the seed. However, if I leave the seed on the soil surface, frost seeding doesn’t work.”

He explains that frost seeding is a way to give spring wheat an early start, because as soon as the temperature rises above about 2 C, the frost-seeded wheat seeds will start growing. An early start helps advance the crop’s maturity so that it heads closer to June 21, the longest day of the year. With longer hours of sunlight, there’s more photosynthate for grain fill, so yields will be higher. In addition, an early start allows the crop to make use of early spring moisture, which also helps yields.

Frost seeding is not risk-free – the crop could start growing in a warm spell and then be damaged if severely cold weather follows. For example, southern Ontario often gets a warm spell in January followed by some quite cold weather, so frost seeding in December can be quite risky. But Johnson has had good results there with frost seeding between late January and March.

“In my estimation, the risk of crop damage is reasonably low. Wheat’s growing point doesn’t come above the ground until the plant has four leaves and has tillered. So it’s quite a period of time before that growing point becomes more exposed to potentially damaging temperatures,” he notes. “The risk is low, while the potential for reward is reasonably high – I can potentially gain perhaps 15, 20, 25 percent in yield. I like those odds.”

Johnson thinks frost seeding of spring wheat could be worth exploring in Western Canada; for instance, he says, barley is frost seeded in Montana, which has a climate more like that of the Canadian Prairies. Also, Dr. Dwayne Beck of the Dakota Lakes Research Farm in South Dakota has studied dormant seeding of spring wheat and has developed planting recommendations for conditions there. Indeed, in a recent article, Beck states that dormant seeding is the normal practice for spring wheat production at Dakota Lakes.

Narrower rows

Johnson believes narrower rows could also increase wheat yields on the Prairies. “No other region in the world at the latitude of Western Canada would consider seeding in 12-inch rows. In England, France, northern Germany, even Afghanistan, they are on at least a seven-inch or a 7.5-inch row, and in the really productive regions where they really push yields, they are on four-inch rows.”

He can see why growers with large acreages would want to go with 12-inch rows. “With 12-inch rows, you have less shanks, so you can pull a 90-foot 12-inch seeder a whole lot easier than a 90-foot seven-inch seeder, and you can plant more acres per day. But I’m not interested in more acres; I want more yield per acre.”

According to Johnson, with 12-inch rows, growers are losing on yield because the crop doesn’t canopy early enough, so it’s not as competitive with weeds and it doesn’t make use of the available sunlight as well as it could. He suggests Prairie growers consider a 7.5-inch row, which is what Ontario growers use.

“The farther north you go, the more response there should be to narrower rows. For example, look at the New Liskeard [Ontario] region. It is one of the pockets of agriculture in northern Ontario; it’s drier than southwestern Ontario and more northerly, so it’s more like Prairie conditions,” says Johnson. “At New Liskeard, we get a four percent yield boost by going from 7.5-inch to four-inch rows. So I think there could be some yield benefit to narrower rows in Western Canada.”

Other ideas to bump up yields

Johnson offers some other possibilities for boosting wheat yields, such as using certified seed, basing seeding rates on target plant populations rather than bushels per acre, and spreading crop residues evenly.

He is also a strong believer in seed treatments. “Based on our Ontario data, there’s a very consistent three to five percent yield gain from seed treatments. If I gain four percent on 50-bushel wheat, that is a 2-bu/acre gain, which is $16 at today’s prices. The seed treatment costs $2. So why not just treat your seed?”

Seeding depth is another key factor, but he says growers need drills that sense seed depth right at the opener, not behind or ahead, to achieve better seed depth placement.

Choosing the right variety is also incredibly important when you’re trying to push wheat yields. “Some genetics simply don’t have the upper-end yield potential to be pushed,” notes Johnson. “We’ve seen that in Ontario; we have some varieties that respond twice as much as other varieties to increased management.”

March 26, 2013 By Carolyn King

A 150 bu/acre wheat possible in Western Canada? A cereals specialist from Ontario thinks so. How can Prairie growers ramp up spring wheat yields? Sometimes a view from outside can offer a fresh perspective.

A 150 bu/acre wheat possible in Western Canada? A cereals specialist from Ontario thinks so. How can Prairie growers ramp up spring wheat yields? Sometimes a view from outside can offer a fresh perspective.