Features

Agronomy

Genetics/Traits

Pests on the wind

It really does ‘rain’ moths and rust spores.

April 8, 2008 By Donna Fleury

Many crop pests are migrants from other locations, usually the US and even as far south as Mexico. Researchers have been looking for a way to anticipate when these pests might arrive in western Canada so that they can provide the industry with an advance early warning system for pest problems and control strategies. Using a system of wind trajectories and pest population assessments, researchers from Environment Canada and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) have been collaborating for 10 years to develop this successful pest forecasting system.

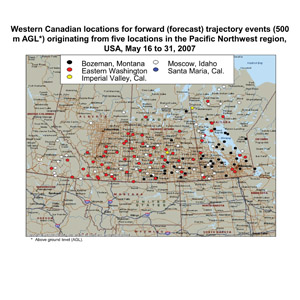

| Figure 1. Western Canadian locations for forward (forecast) trajectory events (500 metres above ground level) originating from five locations in the Pacific North West region in the US, May 16 to 31, 2007. Source: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. |

|

“We selected the diamondback moth to use as a protocol to determine if analysis of wind trajectories would provide the information we are looking for,” explains Dr. Julie Soroka, research scientist at the AAFC Saskatoon Research Centre. The diamondback moth, a seasonal migrant to the prairies, is a serious crop pest worldwide for canola, vegetable and other cruciferous crops. “Diamondback moth can be a huge problem when it arrives early in western Canada, giving it enough time for successive generations to build up, resulting in damaging numbers in the summer.”

Soroka explains there are three factors needed for pest migration to occur, all of which must coincide to get movement. First a source area is required for the pest and a reason for those pests to move. “The reason to move might be declining food sources or over-crowding, or in some species there is a physiological requirement to move,” says Soroka. Secondly, the pests need a means of transportation, which is typically movement by wind and jet streams. “The third factor is the requirement for an event to bring the organism out of the jet stream,” says Soroka. Once these small pests get up to 1000 or even 5000 feet, movement is mainly passive. “A low pressure system is considered the principal descent event, where all of a sudden the winds die down and rainfall typically occurs. Even trace amounts of precipitation can be enough to bring the pests down to the ground. At this point it can literally rain moths or rust spores.”

Researchers selected several locations to measure wind trajectories, both source locations where the winds were coming from and destination locations where the winds arrived in western Canada. “We initially selected 10 source areas for diamondback moth, including the crucifer vegetable growing areas of central Mexico, the Great Plains from Texas through the northern states and the central valley of California,” says Soroka. In western Canada, 16 destination locations were selected. Pheromone traps were also set up at the destination locations as a method of correlating diamondback moth numbers with wind trajectories.

“We begin monitoring the wind trajectories in April from the source locations,” explains Dr. Owen Olfert, research scientist with the AAFC Saskatoon Research Centre. “We’re not sure whether it is global warming or not, but it seems the diamondback moths are arriving a bit earlier every year.” The first wind trajectories monitored are winds coming from central Mexico, Texas and California where populations begin building up earlier than further north. If the winds are right, the diamondback moths can disperse up to destinations in western Canada in a period of four to five days.

“Rarely do we get a real influx of diamondback moth that will cause a problem right away, therefore we call it an early warning system,” says Olfert. “Usually they need one or two generations in western Canada to build up the numbers before it becomes of economic importance.” Another development has been the ability to provide an early warning system for insecticide resistant populations of diamondback moth.

|

| Diamondback moth can travel from as far away as Mexico. Photo Courtesy Of AAFC, Saskatoon. |

“Worldwide, diamondback moth is one of the insect pests with resistance to many insecticides,” explains Olfert. Not every population is resistant to the same insecticide, it depends on what products producers have been using for control. “Therefore, if we get a population of diamondback moth coming up from a certain source location, and we know there are resistance problems to pyrethroids for example, then we can urge growers at the time of control to consider a product with a different mode of action in case of resistance.”

There have been some reports during the past five to 10 years where growers have used a product for diamondback moth control and were not satisfied with it. Researchers did go back in a few cases and check, and in some cases there had been reports of resistance in the US. So this provides an early warning system for potential insecticide resistance as well.

“We started monitoring about 19,000 wind trajectories from the US and found that in many cases there was a very good correlation between a specific event at certain southern locations, and wind trajectories crossing a certain point here in Canada four or five days later,” says Soroka. “A few days after that we began to pick up moths in the pheromone traps.” The results showed a good correlation between source winds in central Mexico, southern US and California to pest populations in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, but researchers could not find a good correlation with the appearance of diamondback moth in Alberta. “We suspect that the wind trajectories from the Pacific North West (PNW), including Idaho, Washington and western Oregon, are the ones bringing diamondback moth into Alberta, but we need to confirm that.”

Olfert adds that along with tracking wind trajectories from the south, they also track trajectories from west to east across Canada. “We’ve discovered that the westerly winds, which are common across the prairies, often travel east across Canada, migrating our pest problems from the prairies to locations in eastern Canada. So now we monitor north-south wind trajectories and west-east as well.”

Today there are about 60 destination sites across Canada and 25 source sites in the US that are assessed throughout the growing season every year. Olfert notes that the process of receiving the trajectory data from Environment Canada has also changed to streamline the process for everyone. Initially, Environment Canada provided daily wind trajectory maps, but as the project grew it became too time consuming to manually inspect all those maps. Now the raw data that the wind trajectories are drawn from are compiled into a user friendly database on a daily basis, allowing researchers across Canada to create timely reports for specific locations of interest.

“We have good collaboration with the provincial entomologists and pathologists across the prairies and the Peace region of British Columbia, as well as industry organizations such as the Canola Council of Canada, which put out the advance warnings as required,” says Olfert. “The project started a number of years ago with entomologists and we’re now recognizing its potential for insects that transmit diseases, such as leaf hoppers that transmit aster yellows and for windborne crop diseases.” Entomologists and pathologists are successfully using this wind trajectory model as a means of forecasting potential pest problems and providing an advance warning to the industry.

Wind trajectory model expands to crop diseases

Realizing the value of wind trajectory models for providing advance warning of insects, entomologists approached pathologists to see if the model may work for windborne crop diseases. Cereal rust spores, which cause leaf and stem rust problems in many cereal crops across western Canada, are known to travel long distances on wind currents from the US. Dr. Kelly Turkington, research scientist at the AAFC Lacombe Research Station, is leading an initiative to identify wind trajectory events that may possibly bring rust spores into western Canada from epidemic areas in the central US and PNW.

“Our main focus is on cereal rusts and the movement up from Texas and through the central states such as Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska and into western Canada,” explains Turkington. This well established route is referred to as the Puccinia Pathway and is the main cereal leaf and stem rust migration pathway. “Typically the pathogen overwinters in cereals in Texas and other southern states, and begins to cycle early in the spring, moving in short steps through the various states and into western Canada.” There are also some wind trajectories that appear to bring rust spores directly up from the Texas to Nebraska corridor into western Canada.

| Figure 2. Wind trajectories can be used to monitor pest travel. |

|

“We’re also looking to the PNW, particularly eastern Washington, north-eastern Oregon and western Idaho as a pathway for stripe rust, which potentially overwinters there building up on winter cereals in the spring, then moving into western Canada.”

The key factors needed to spread rust problems are similar to other pests, such as diamondback moth. There must be a source location, where the disease needs to be at epidemic levels, there needs to be a wind event to carry the spores into western Canada, followed by a rain event to deposit the spores to the field level. Whether or not the rust spores can successfully infect cereal crops depends on weather conditions, host resistance and crop growth stage. Favourable weather conditions and susceptible host crops will promote rapid cycling of rust pathogens on cereal crops with trace levels of disease having the potential to become much more serious as the growing season progresses.

Rust spores are adapted for long distance dispersal, with thick walls and very dark pigmentation, protecting them from radiation. The longer the spores are in the air, the less viable they are. Spores can reach heights of 500 to 3000 metres and travel several hundred kilometres before being deposited. From the central US, such as Kansas or Nebraska, the spores can arrive in two or three days. In the prairie region, the first appearance of rust will typically be in mid to late June, likely as a result of rust spores arriving one to two weeks earlier. From the PNW, the data shows the spores can travel to western Canada in a day or even less under the right conditions.

“With stripe rust, we’re also concerned with a potential buildup in southern Alberta that can be moved through wind currents up to central Alberta and the Edmonton area. So we’re not only looking at wind trajectories from various US source locations, but also from south to central Alberta.”

During 2007, Turkington analyzed wind events and trajectories for selected destinations in western Canada on a weekly basis, and received regular updates on rust development in the various US source locations through the Cereal Rust Bulletins published by USDA, as well as information from fellow pathologists and extension staff from the three prairie provinces. Turkington combined all of this information together with environment data from Environment Canada to assess the potential risk for western Canadian growers.

“If the wind trajectories are right, their frequency is increased, the weather events have been favourable to bring spores down to the field level and environmental conditions favour spore germination and infection, then we need to begin looking for rust symptoms in our cereal crops,” says Turkington. “Ultimately, it is a heads up to a potential epidemic, and gives growers and industry agronomists time to scout susceptible fields properly and plan for spraying if required.” Turkington provides reports to provincial pathologists and industry leads for communication to growers.

“It is very exciting to be able to take the science and connect it right to what the grower is facing or doing in the field,” says Turkington. “We do need to ground truth some of the research information and we are already looking at some options for the summer of 2008.” As with insect pests, like diamondback moth and leaf hoppers, the wind trajectory models also are proving to be a useful disease forecasting tool for diseases such as cereal rusts. -end-

The Bottom Line

Advance warning for any pest would certainly add another tool to our management toolbox

especially fine-tuning our field scouting in-season. We have found quite often that when

looking for wheat midge we will continuously monitor for the pest and after not finding significant levels, it shows up the night after we quit looking. Narrowing down the scouting window and even determining if the pest may even show up each season would certainly simplify the monitoring process. Warren Kaeding, Churchbridge, Saskatchewan.