Features

Agronomy

Other Crops

Non-GMO path opens for flax and canola

Somewhere in San Diego, future Canadian canola and flax products are being developed right now in high-tech laboratories and greenhouses. Cibus Global, a trait development company formed in 2001, is developing canola varieties and is doing research on behalf of the Flax Council of Canada. The initial task for Cibus is to build-in herbicide tolerance, without GMO technology, for flax, canola and potato.

September 21, 2010 By John Dietz

|

|

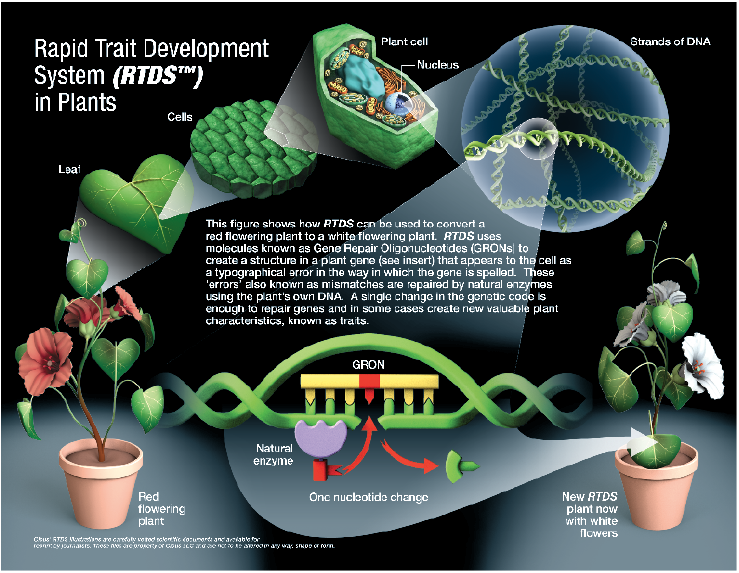

| This illustration from Cibus Global depicts the course of the breeding process. Illustration and photo courtesy of Cibus Global.

|

Somewhere in San Diego, future Canadian canola and flax products are being developed right now in high-tech laboratories and greenhouses. Cibus Global, a trait development company formed in 2001, is developing canola varieties and is doing research on behalf of the Flax Council of Canada. The initial task for Cibus is to build-in herbicide tolerance, without GMO technology, for flax, canola and potato.

Cibus Global has also signed a marketing and distribution agreement for commercial canola products, in December 2009, with independent seed company BrettYoung. The 75-year-old, family-owned company markets canola through Western Canada and North Dakota.

The Cibus-owned trait development process is called Rapid Trait Development System (RTDS), and is a directed mutagenesis. RTDS-directed mutagenesis enables scientists to make precise changes in a natural DNA sequence, without introducing “foreign” DNA. Once Cibus scientists know the target gene associated, and the targeted sequence change for the particular trait, they use a natural gene repair process. This enables a plant to make its own natural changes to reach the desired trait.

From start to finish, mutagenesis can lead to a new commercially ready product in six to seven years. The process is about three years faster than a genetically modified crop timeline. Much of the saving is due to faster regulatory approval for RTDS technology.

RTDS is relatively new, but mutagenesis is not. Canola growers have benefited for a decade from two mutagenesis-derived products, Clearfield canola and Nexera canola. Mutagenesis also is behind popular varieties of sunflowers and watermelons.

|

|

| Grace Gamalong, a research associate in cell biology with Cibus Global, cultures canola cells and observes cell growth with a stereo microscope.

|

Cibus partners

“A typical RTDS trait development project at Cibus requires three to four years of development work in the lab for each targeted crop and, depending on the trait, costs approximately $7 million,” says David Voss, vice-president of commercial development with Cibus Global’s office in Woodbury, Minnesota. “That’s about one-tenth the cost to get a GMO product to market.”

The new trait is turned over to the sponsoring partner for trait integration using traditional breeding methods.

With nine partners worldwide, Cibus is currently using RTDS to develop traits for nine crops, says Voss. The company is involved in four crops with five partners for Western Canada.

Cibus recently completed a contract with BASF to develop a new trait in canola. That trait now is being prepared for integration into registered hybrid canola varieties. RTDS can work with most major herbicide chemistries to form herbicide tolerance, he says. Cibus has its sights on five different herbicide family classes of chemistries. “We are herbicide-neutral. We actually look for the best fit solution for farmers. Then we develop a trait in plants to be tolerant,” Voss says. “In addition to herbicide traits, we’re working on oil modification for making healthier vegetable oils. Other value-added traits include a solution to potato bruising which costs North America’s potato industry nearly $300 million a year. Additionally, Cibus is working to make more efficient biofuels.”

Flax outlook

In a February 2010 announcement, federal Agriculture Minister Gerry Ritz said the Flax Council of Canada will receive up to $4 million from the Developing Innovative Agri-Products program (DIAP) to help produce a herbicide-tolerant Canadian flax.

Herbicide-tolerant flax “would be a tremendous tool for the farmer to have,” says Barry Hall, president and CEO of the Flax Council of Canada. “You could have a potential 20 percent yield increase without changing the variety, because you avoid damaging the crop while gaining excellent weed control. It’s a win-win situation.”

The promised DIAP funding, along with a further $1.5 million from the flax industry, enabled the Flax Council of Canada to partner with Cibus Global. At the time, the council was engaged in an international controversy over the discovery of trace amounts of discontinued GMO flax in Western Canada. Between October 2009 and early 2010, Canada lost most of its export market for flax due to the contamination and zero tolerance policies for GMO products. “It’s somewhat ironic this GMO fiasco came along now,” says Hall. “We were in discussions with Cibus for at least a couple years before this, looking for development of a flax that would be non-GMO. Now, they won’t be able to develop the variety fast enough, short-term.”

Glyphosate tolerance would be the first of several traits to be stacked on a new flax platform. New fatty acid profiles and improved disease resistance may be added later.

Genetic stock is being supplied by Canada’s flax breeding programs at the Crop Development Centre at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s research station at Morden, Manitoba, and Viterra. Growers will pay a fee for the added-value trait. The Flax Council of Canada also intends to sponsor new research. The remaining portion will go to Cibus, as owner of the technology. “At the end of the contract, if all goes reasonably well, we’ll have a product to take to the field. Then, it will still be a few years away from commercial sales,” Hall says.