Features

Environment

Soil

Moisture stress and crop performance

Could crop response to different moisture regimes be assessed as part of Manitoba’s variety trials?

July 8, 2022 By Carolyn King

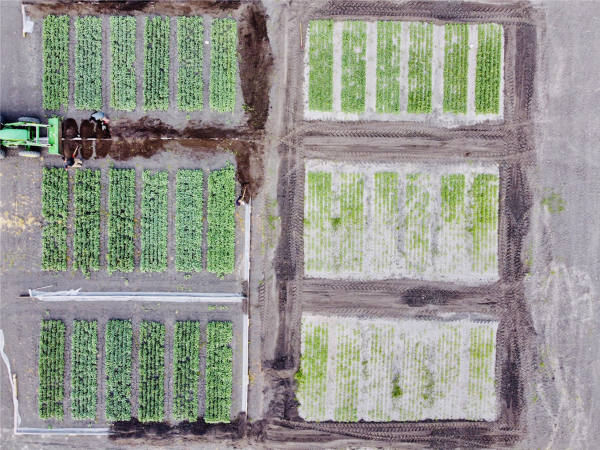

Installing rain shelters over the Portage plots to simulate drought conditions.

Photos courtesy of Curtis Cavers.

Installing rain shelters over the Portage plots to simulate drought conditions.

Photos courtesy of Curtis Cavers. The Prairie weather in recent years has vividly shown just how damaging flooding and drought stress can be to crop yields. Manitoba researchers wondered if data on varietal responses to different moisture regimes might help growers in dealing with moisture extremes. So, their project is exploring if and how crop response to moisture stress might be evaluated as part of provincial variety trials.

“This project is looking at moisture stress – both excess and deficiency – by timing of the stress, as well as by crop type and variety. The first two factors are more agronomic in nature. The crop variety factor is of interest to determine whether there are any differences among selected crop varieties for yield stability or possible yield advantages that could be applied in precision farming scenarios,” explains Curtis Cavers, an agronomist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC).

Cavers is collaborating on this project with Dr. Nirmal Hari, an applied research specialist with Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development. Hari is based at the Prairies East Sustainable Agriculture Initiative (PESAI) Diversification Centre.

Installing berms around the Arborg plots for the flooding treatments. Photo courtesy of Nirmal Hari, PESAI.

The project’s two field sites are at the AAFC Research Farm at Portage la Prairie and at PESAI’s Arborg location. The project targets spring wheat and canola because they are widely grown crops and because different varieties of each crop type are easily available.

“Depending on the site and year, we tried to compare six different crop varieties of both crops,” Cavers says. He adds, “This project is modest in the number of varieties tested, as we were focused on working out the details in trying to impose moisture stresses as evenly as possible and to impose those conditions without killing the crop stands but causing enough damage to impair crop growth and reduced yields.”

He explains the project’s focus on both very wet and very dry conditions was more by accident, rather than by design. “Manitoba crop insurance data has shown over the long term that excess moisture and lack of moisture (drought) are nearly equal in their frequency of causing crop yield loss and subsequent claims. When this project was initiated almost three years ago, Manitoba was in the midst of dealing with several growing seasons of excess moisture being the primary limiting factor to crop production. However, we also expected it was only a matter of time before we experienced the next most common limitation to crop production in Manitoba, which is a lack of moisture.”

In 2019 and 2020, both sites simulated excess moisture conditions, with additional water applied at early as well as late growth stages, and compared those plots to check plots with no water application. At both sites, the project team installed berms around the appropriate plots and then flooded those plots with water from their irrigation systems.

In 2021, the Arborg site followed the same experimental design as in 2019 and 2020.

However, at the Portage site, Cavers needed to adjust the design to simulate very dry conditions rather than very wet. That change was necessary because the farm’s irrigation water supply was depleted, making it impossible to add enough water to create excess water stress. The team installed plastic rain shelters over the appropriate plots for select periods in June (early growth stage) and July (late growth stage) to simulate early versus late season moisture deficiencies.

At each site, the team measured precipitation, collected data on crop growth and yield, and monitored soil moisture at different depths in the soil profile.

Some preliminary findings

Cavers expects to have the project’s final report completed by March 2022, but he has some initial results that he can share.

“One key finding is that, in general, later moisture stresses are more damaging to crop performance, whether the stress is excess water or lack of water. Our data showed that there seems to be a more negative impact on yield as the stress occurs closer to the plant’s reproductive stage.”

He adds, “Of course, if you have extreme moisture or extreme drought early in the season that wipes out the crop stand, that will have a major impact on yield. However, we were trying to not wipe out the stand; we wanted to find that sub-lethal level of soil moisture where we would hurt the crop but not wipe it out.”

Regarding the crop type comparison, Cavers says, “As you would expect, wheat and canola responded a little differently to moisture stress. However, we didn’t find that one crop was necessarily more stress tolerant than the other. Both crops are in that mid-range of being able to tolerate extremes of moisture. In general, different crop types respond differently to moisture conditions; for instance, oats tend to be more moisture-tolerant than wheat, and soybean is definitely more tolerant of excess moisture than canola.”

Their results also show that crop type is more important than variety when it comes to moisture stress responses.

“We found that most crop varieties tend to perform consistently relative to one another regardless of moisture conditions. In other words, if a variety is higher yielding under normal or optimum conditions, it tends to remain higher yielding than other varieties under more extreme conditions, even though its actual yield has been reduced because of the excess moisture,” Cavers says.

“However, at Portage, there was a rare instance where one wheat variety yielded poorly compared to other varieties under excess moisture conditions in 2020, and then yielded better than the other varieties in the following year under dry conditions. So, there might be the odd variety that you could look at if you were targeting, say, variable planting by landscape position.

“But by and large, you are better to just go with the information that growers have always used for variety selection – which varieties are the highest yielding, which ones are the most disease resistant, and so forth.”

At present, Cavers and Hari are continuing with the data analysis and interpreting how the different moisture contents at different soil depths are correlated with crop growth and yield.

Simulation challenges

This project is also providing some insights into factors to consider for future work involving simulation of very wet or very dry conditions as part of variety evaluation trials.

“To apply these moisture treatments is easier said than done,” Cavers says. “You need a lot of labour, whether you are installing berms around the plots or you’re using your irrigation equipment fairly aggressively.”

The researchers also found that it was sometimes difficult to apply enough water to simulate really wet conditions. “In a wet year, that’s not a problem – if you get a two-inch rain and then you add an inch of irrigation, that does the trick. But under dry conditions, it becomes much more of a challenge to put on enough water to hurt the crop. You can only apply so much water in a given time period by irrigation, and our heavier textured soils can store a lot of water. So, if the natural precipitation was lacking, the applied water would usually just be enough to get the plots to the optimum moisture range, but not beyond that to the excess range,” he notes.

“And then in 2021, we were trying to do our drought simulation in a drought, so even our rain-fed control plots had sub-optimal yields. In field research, you sometimes don’t get the contrasts that you’re looking for.”

Cavers has found it interesting to tackle the many hurdles involved in comparing moisture stress regimes in a field context. And dealing with those hurdles is providing some answers on such things as the effects of moisture stress timing on crop growth, and determining the amount of moisture stress needed to hurt a crop stand without wiping it out completely.

This project is funded by the Manitoba Crop Alliance (formerly the Manitoba Wheat and Barley Growers Association), AAFC at Portage la Prairie, and Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development (via PESAI) at Arborg.