Features

Other Crops

Let them eat quinoa

Lots of insects show up to the dining table, but only two main culprits take the cake.

August 13, 2020 By Jennifer Bogdan

Figure 2: Goosefoot groundling moth adult. PHOTO COURTESY OF SHANE HLADUN.

Figure 2: Goosefoot groundling moth adult. PHOTO COURTESY OF SHANE HLADUN. Five-year olds may turn up their noses at the sight of quinoa on their dinner plates, but for creatures with six legs and a hardy set of mandibles, quinoa is the cream of the crops.

While traditionally grown in South America, quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) has expanded its presence in the Prairie provinces since it was first grown in Saskatchewan in the early nineties. Recognized as a pseudo-cereal (a non-grass plant that can be used as a cereal), quinoa is increasingly consumed for its high protein and mineral content, as well as its gluten-free and antioxidant properties. The Prairies now produce more quinoa than anywhere else in North America, with approximately 13,000 acres contracted for 2020.

One of the challenges that growers started experiencing in 2016 and 2017 was extensive unidentified insect damage in the new fields of quinoa now dotting the landscape. Boyd Mori, assistant professor of agricultural and ecological entomology at the University of Alberta, led the first study to investigate and develop monitoring tools for insect pests of quinoa on the Prairies.

“As quinoa is a relatively new crop to Western Canada, little information was known on the insects that attack it. Determining the life cycle and damage caused by insect pests were the first steps in creating an integrated pest management (IPM) program for quinoa growers,” Mori says.

For this study, Mori collaborated with the Farm Services team at NorQuin, including Marc Vincent, Kaila Hamilton and Derek Flad, as well as Tyler Wist, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatoon, and Kirk Hillier, professor of chemical ecology at Acadia University in Nova Scotia. The research took place during the 2018 and 2019 growing seasons at four research sites and eight to 10 commercial quinoa fields in Saskatchewan.

Table for 18, with two VIPs (Very Important Pests)

In total, 18 insect species have been identified as pests of quinoa. Of greatest concern are the goosefoot groundling moth (Scrobipalpa atriplicella) and the stem-boring fly Amauromyza karli, which together can cause upwards of 100 per cent yield loss in severely infested stands.

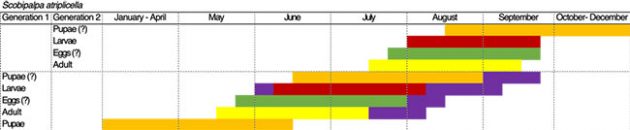

The goosefoot groundling moth is a species introduced to North America that is now widespread. Its other host plants include lamb’s quarters (Chenopodium album), sugar beet, and saltbush or orache (Atriplex spp.), all of which belong to the same Amaranth family as quinoa. The researchers discovered that goosefoot groundling moth has two generations in Saskatchewan (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Estimated phenological development of the various goosefoot groundling moth (S. atriplicella) life stages based off emergence cage, plant and sweep net samples conducted at four experimental plots and several commercial quinoa fields throughout Saskatchewan. The length of the pupal and egg stages are estimates, as no pupae or eggs were found in samples collected from the field. Purple bars indicate extensions of the particular life stages based on 2019 observations.

The small, brown-grey adult moths appear in mid-May and lay eggs on quinoa plants (Figure 2). The first-generation larvae initially mine through leaves but later larval stages migrate to the growing points, where they web leaves together and feed on the developing panicles (Figures 3 and 4). The second-generation larvae appear in early August and continue to feed on the panicles. It is suspected that full-grown larvae then drop to the soil to pupate over the winter.

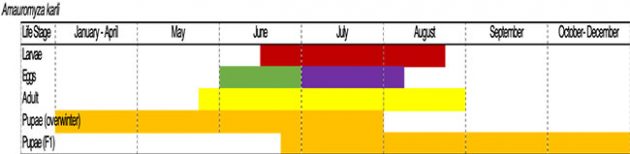

The other main insect pest of quinoa is stem-boring fly (A. karli), part of a family of flies whose larvae are leaf miners. One prolonged generation is produced in Saskatchewan each year (Figure 5). Adult flies are present from late May to the end of August (Figures 6 and 7). Small larvae hatch from eggs, then enter the leaves where they feed between the upper and lower cell layers of the leaf, creating visible “mines.” Eventually, the larvae mine their way down the petiole of the leaf and into the main stem, where feeding reduces the flow of water and nutrients to the developing seeds, and also makes the plants more susceptible to lodging (Figure 8).

Early stem feeding (i.e. at the four- to six-leaf stages) will cause extensive damage, whereas later stem feeding (at panicle emergence) is much less severe and plants will still be able to set seed. Mature larvae chew their way out through the stems, producing characteristic “pin-holes” through which they exit and drop to the soil to pupate for the winter (Figure 9).

Figure 5: Estimated phenological development of the various stem-boring fly (A. karli) life stages based off yellow sticky card, plant and sweep net samples conducted at 4 experimental plots and several commercial quinoa fields throughout Saskatchewan. Purple represents the 2019 extension of the egg-laying period by five weeks into the first week of August.

Chart courtesy of Boyd Mori and Tyler Wist.

Cutworms and flea beetles can also severely reduce quinoa plant stands. In addition, a complex of plant bugs can cause feeding damage due to their piercing-sucking mouthparts, although their impact on yield is unknown at this point (Figure 10). Later in the season, Bertha armyworm can cause economic damage to the panicles; Bertha armyworm larvae have been observed moving from canola fields into adjacent quinoa fields.

Scouting is a critical part of a well-balanced IPM diet

NorQuin agronomists strongly recommend that growers adopt a set scouting schedule to assess insect numbers in their quinoa fields. “Someone should be in the field every two to three days to monitor pest pressure. While the agronomics and economics of this crop are attractive to skilled growers in Western Canada, quinoa is still a specialty crop that requires specialty attention,” they say.

The research project has led to the development of a pheromone monitoring tool for goosefoot groundling moth that will help determine population densities. For the stem-boring fly, yellow sticky cards were found to be more effective than sweeping in measuring the adult fly population.

Mori emphasizes that proper insect identification is important. “Initially, there were cases of goosefoot groundling moth larvae being confused for diamondback moth larvae, as they wriggle like diamondback moth larvae and can drop from a silk thread like diamondback moth larvae. Diamondback moths are very host-specific and their main host crop in the Prairies is canola,” he says.

The researchers also remind growers that although the stem boring fly is a leaf miner, not all leaf miners are A. karli. If leaf-mining is observed, growers should automatically be examining stems for evidence of larval feeding.

Consistent and continuous scouting is especially critical for monitoring goosefoot groundling moth. The damage caused later in the season by the second-generation larvae is typically worse than that of the first-generation larvae. “It’s harder to see the larvae on the yellowish-brown plants and panicles at this time, compared to green plants with emerging panicles earlier on. Also, growers are typically beginning harvest in pulse crops and potentially cereals when this second generation appears, and scouting is not always in the forefront of their minds at the time,” Hamilton explains.

Control options are currently limited

FMC has received an emergency use registration for beet webworm control in quinoa with Coragen insecticide for the 2020 growing season. Otherwise, there are no insecticides registered for use on quinoa. Vincent says that NorQuin is utilizing the Minor Use Program and funding private trials to pursue label expansions to include quinoa on common products used in Western Canada. They are also quantifying damage in these trials to help develop economic thresholds for insect pests in quinoa for when products become available.

Over the course of the research project, Mori said several generalist natural enemies of insect pests were found, including green lacewings, ground beetles, ladybird beetles, damsel bugs, and minute pirate bugs, but their impact on goosefoot groundling moth and the stem-boring fly populations have not been studied. More hope may lie in the two parasitoids found – a Braconid wasp in the goosefoot groundling moth larvae and a yet-to-be identified parasitoid in the stem-boring fly larvae.

Figure 10: Feeding by plant bugs produces small circular punctures in the leaves of quinoa. From left to right, the least damage to the most damage. Photo courtesy of Boyd Mori.

Despite the insect challenges, NorQuin’s experience has shown that growing quinoa can provide economic and agronomic benefits to the farm. “Growers that commit to intensive management in terms of field selection, scouting, and harvest timing will see positive returns on a five-year average,” Flad says. “Quinoa is not susceptible to clubroot like canola is, or Aphanomyces root rot like pulses are. Therefore, it can be a profitable addition to crop rotations in Western Canada, both in terms of net returns as well as a farm-wide IPM strategy to reduce pathogen load for subsequent canola or pulse crops.”