Features

Agronomy

Irrigation

Irrigated potatoes need three- to four-year rotation

Back in 1997, when Manitoba’s potato industry was in an expansion phase, industry and researchers wondered if irrigation and good management could enable them to produce potatoes on a field as frequently as every second year.

April 28, 2010 By John Dietz

Back in 1997, when Manitoba’s potato industry was in an expansion phase, industry and researchers wondered if irrigation and good management could enable them to produce potatoes on a field as frequently as every second year.

|

| A long-term research study has determined that longer rotations provide greater benefits to potato crops. Photo courtesy of Dr. Ramona Mohr, AAFC.

|

They set up a long-term study to get answers they could trust. “The study was initiated in 1997; the rotations were initi-ated in 1998,” says Dr. Ramona Mohr, lead scientist in the collaborative effort. Mohr is a sustainable systems agronomist at the Brandon Research Centre of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). Most of her work deals with potato rotations and potato nutrient management.

Known as the Carberry Potato Rotation Study, it was set up at the Canada-Manitoba Crop Diversification Centre (CMCDC) near Carberry, Manitoba. CMCDC and AAFC were partners, supplying resources for the study. Scientists from the University of Manitoba also participated. “Our overall objective was to look at two factors. Which crop rotation would optimize yield and quality while minimizing pest problems? Second, which rotations would also maintain or enhance soil quality?”

The rotation study yielded a great deal of other information that will be useful to the industry, Mohr said. Her report on the rotation options was to be presented in late January to Potato Days in Brandon and, a week later, at the Manitoba Soil Science annual meeting.

Lab analysis is still underway with more results expected later in 2010.

The study examined production results from rotations of two, three and four years. All of the plots were in similar growing conditions. The potatoes were irrigated but the non-potato crops were not irrigated.

Each rotation had two variations. The short rotation was either potato-canola or potato-wheat. The three-year rotations were either potato-canola-wheat or potato-oat-wheat. One of the four-year rotations was potato-wheat-canola-wheat; the other was potato-canola-alfalfa-alfalfa. The alfalfa was first underseeded and then managed as a hay crop.

The study needed to be long, with three full repetitions of the four-year rotation, to give a high level of confidence in the results. The final impression was quite different from the first impression. “The first few years the rotations were established we didn’t really see any effect on yields,” Mohr said. “After that, in some years we did see yield differences among the rotations but there wasn’t any single rotation that consistently out-yielded the rest, in potato yield. Up to about 2006, rotations that seemed to perform a little bit better than the others were the two-year potato-canola, three-year potato-canola-wheat, and the four-year potato-canola-alfalfa-alfalfa.”

|

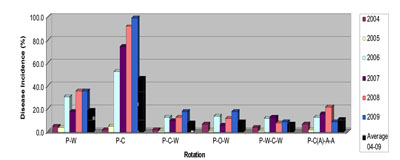

| Incidence of vascular wilt disease in potato as affected by crop rotation (2004-2009). Disease ratings are expressed as the percentage of infected plants per number of plants examined. |

|

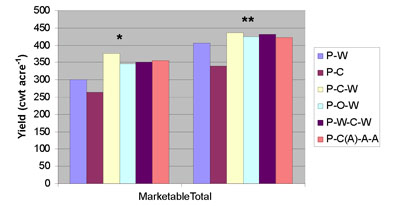

| Effect of crop rotation on marketable yield (>2 inches) and total yield of potato in 2009. (** Significant at the 0.01 probability level.) |

However, when the results were all analyzed from the 2007 growing season, there appeared to be a change. That change was repeated in the 2008 and 2009 seasons. “The most interesting has been the last three years. During that time we’ve seen lower yields in the short two-year rotations compared to the three- and four-year rotations,” explains Mohr. “Our plant pathologist, Dr. Debbie McLaren, at the same time has been finding much higher levels of vascular disease in the potato in short rotations. That’s really the big story coming out of the study.”

By 2009, tuber yields for the short rotations averaged only about two-thirds of yields in the longer rotations. Yields were compared using tubers with a diameter of at least five centimetres.

In the field during the final three seasons, researchers could see obvious signs of a disease called vascular wilt. “You tend to see leaf yellowing followed by wilting, senescence, and death of the plants before normal maturity” she said. “In 2009, 99 percent of the potato plants surveyed in the two-year potato-canola rotation were showing evidence of vascular wilt. We were seeing very high levels of that disease.”

The highest disease incidence, and most severe, was in the potato-canola rotation. Potato-wheat showed the next highest level. It is thought that the vascular wilt contributed to lower yields in these short rotations.

Vascular wilt pathogens can overwinter in a field. Results of the study indicate there is less vascular wilt risk when the rotation is extended beyond one year.

The study concludes that “the performance of a given rotation in the years immediately after a crop rotation system is established may not reflect its performance in the longer term. During the initial nine years of the rotation study, consistent effects of rotation on yield were not evident, although there was some evidence of increased potential for disease in the shorter rotations.”

Analysis of the economic data still was underway in mid January. Based on just the yields and disease issues, Mohr said, “So far it looks like the two-year rotations are probably not sustainable here in Manitoba in the long term.”

Changes in soil chemistry and physical properties, in microbial populations, in wireworm damage and in weed populations were monitored during the 12-year crop rotation at Carberry.

It may be worth the investment, she said, to take the study a few years further in a somewhat new direction. “We’re interested in whether we can reverse this effect. Can we apply management practices that would reduce the disease load and allow us to bring those yields up again? Can we turn this thing around?” she asked.