Features

Agronomy

Insect Pests

What we know (so far) about the new midge on the Prairies

A midge by any other name is still a midge – but it’s not swede midge. That’s the finding of scientists with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), University of Guelph and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). Swede midge had been confirmed by CFIA in 2007, but what had previously been thought of as the swede midge in northeast Saskatchewan since 2007, and in research projects by AAFC starting in 2012, has been confirmed to be a new species of midge.

April 4, 2018 By Bruce Barker

Dried A midge by any other name is still a midge – but it’s not swede midge.

Dried A midge by any other name is still a midge – but it’s not swede midge.

“We were doing some emergence cage studies in 2016 to help determine the life cycle of swede midge on the Prairies and found that we were catching hundreds of adult midges in the cage trap, but no males were captured on the pheromone traps. Pheromones are very, very species specific, so I wondered if there was something wrong with the pheromone,” says Boyd Mori, a research scientist with AAFC in Saskatoon.

Boyd subsequently sent the pheromone traps to the University of Guelph. Researchers there found the pheromone traps were capturing hundreds of swede midge within days. “That made us suspect that something else was going on.”

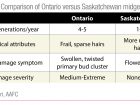

In earlier research by AAFC’s Julie Soroka and Lars Andreassen, which included a distribution survey, life cycle assessment and screening for biological control, they found some key differences between Saskatchewan and Ontario populations of midge.

“By 2016, we were starting to question if the Saskatchewan midge was swede midge,” Mori says.

Swede midge is part of the gall midge family Cecidomyiidae that has more than 6,000 described species. In agriculture, wheat midge, Hessian fly and swede midge are pests that have caused economic damage in Canada. The swede midge is part of the Contarinia species, and is named Contarinia nasturtii. Swede midge was first identified in North America in Ontario in 2001, and has since spread throughout Eastern Canada and much of the northeastern U.S. seaboard as well as Ohio, Michigan, and Minnesota.

Following up on the pheromone issue, Mori also collected larvae of the midge from infested flower buds, and reared them to adults. He sent the adults to Jamie Heal at the University of Guelph for identification. Heal noticed some very small differences between the Saskatchewan and Ontario adult midges. Adult midges from Saskatchewan were also sent to Brad Sinclair with CFIA in Ottawa who also observed differences and was confident that the midges were not swede midge. Subsequent DNA sequencing confirmed that the Saskatchewan midge was not swede midge.

“Only 91 per cent of the DNA sequence had similarity between swede midge and the new midge. Geneticists say you need between 98 and 100 per cent similarity to be considered the same species,” Mori says.

For now, Mori is calling the new species the “canola flower midge.” Sinclair is working on the species description and a name will hopefully soon be established. This is the first confirmation of this midge species anywhere in the world.

What is known about the unknown midge

Soroka’s earlier research on what was thought to be swede midge but was the “canola flower midge” provided some insight into this new midge species. She established that it has one to two life cycles per year. This is important, because in Ontario where the swede midge has up to five lifecycles, the swede midge has time to build populations to damaging levels in one growing season, and the pest can attack several different stages of crop growth.

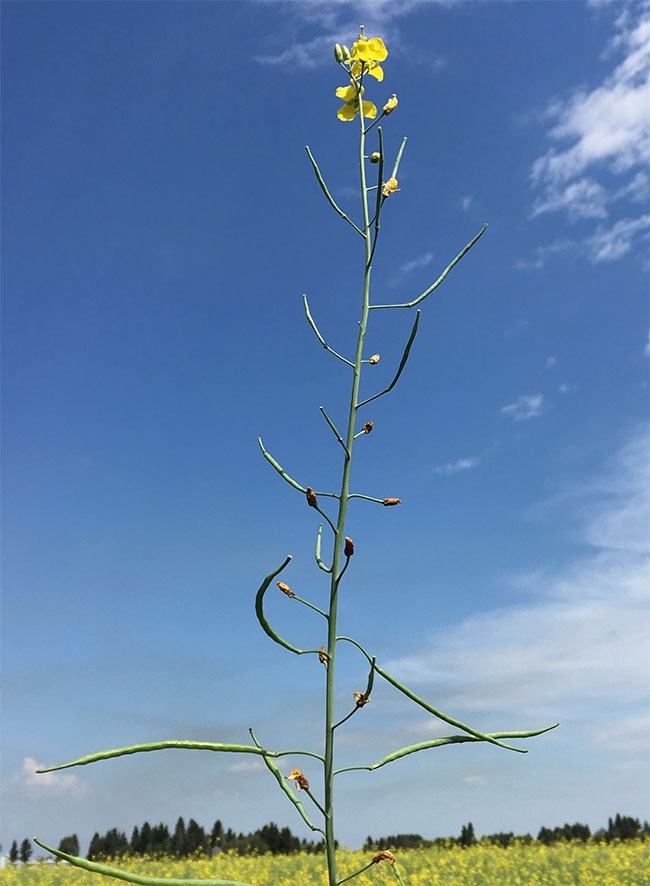

In Saskatchewan, the only place eggs were found was in the developing flower buds. The eggs hatch inside the flower bud and have three larval instars. The larvae cause bottle-like galls to develop at the flower stage instead of pods. If the bottle-like gall is cut open, larvae may be found inside.

Two parasitoid wasps were also found that attack the “canola flower midge.” One is an Inostemma sp. and the other a

Gastrancistrus sp.

“Neither of these parasitoids have been found on swede midge in Ontario,” Mori says.

In 2017, a distribution survey was conducted in Alberta, Saskatchewan and the Swan River area of Manitoba. Approximately 100 fields were surveyed with 100 racemes per field assessed for signs of damage or damage with larvae present. Results showed that the “canola flower midge” is widespread across the northern grain belt of Alberta and Saskatchewan and northwest Manitoba. Scott Meers and Shelley Barkley of Alberta Agriculture and Forestry collected the Alberta data.

“Any damage observed was very low so it is currently unknown if this midge can develop into a pest of canola,” Mori says.

Collaborators to the current research project at the University of Greenwich in the U.K. have identified the pheromone produced by the female “canola flower midge.” Field-testing will occur in 2018 and 2019 to confirm its effectiveness, and this will help establish the distribution of the midge across the Prairies.

Moving forward, Mori and colleague Meghan Vankosky at AAFC Saskatoon are continuing to research the new midge. Their projects include identifying the distribution of both midge species on the Prairies; determining the life cycle of the “canola flower midge” and its potential impact on yield; looking for biological control agents for both species; and confirming the pheromone trapping for the new species.

“If anyone would like to assist in the field surveys for the midge species, they can email me and we can see if we can get the traps and lures used for the survey,” Mori says. (Reach him at boyd.mori@canada.ca)