Features

Cereals

Improving irrigated wheat production

Saskatchewan practices investigated.

August 30, 2021 By Bruce Barker

With intensive management, irrigated wheat profitability can be increased.

PhotoS courtesy of JOEL PERU.

With intensive management, irrigated wheat profitability can be increased.

PhotoS courtesy of JOEL PERU. A farmer survey and research by the Irrigation and Crop Diversification Corporation, at Outlook, Sask., are trying to wring as much profitability out of irrigated spring wheat and durum crops as is possible. The most profitable crops targeted high yields with an adequate fertility and crop protection program.

“Irrigated wheat is one of the crops with lower profitability. It is grown more from a crop rotation perspective to break up the disease cycle with dry beans and canola,” says Joel Peru, irrigation agrologist with the Crops and Irrigation Branch of the Ministry of Saskatchewan Agriculture in Outlook. “Having cereal crops in rotation helps to reduce diseases like Sclerotinia, blackleg and clubroot that can infect some of the following rotational broadleaf crops.”

An irrigation crop survey conducted in the Lake Diefenbaker area in 2020 identified that 32 per cent of the crop mix – about 22,000 acres – was in wheat production. The majority of these acres were hard red spring but there was some durum production as well. In the 2021 Irrigation Economics and Agronomics publication by ICDC, hard wheat with a target yield of 90 bushels per acre (bu/ac) is projected to net out $6 per acre (/ac), and durum targeted at 100 bushels per acre at $158/ac. That compares with pinto dry beans at $516/ac and black beans at $392/ac. The most profitable crops are projected to be seed potatoes at $5,880/ac and table potatoes at $3,941/ac.

With profitability numbers like that, wheat lags, but farmers are trying to squeeze as much profitability out of their wheat rotations. A 2018 farmer survey by ICDC looked into farm-scale practices to investigate best practices for the most profitable crops.

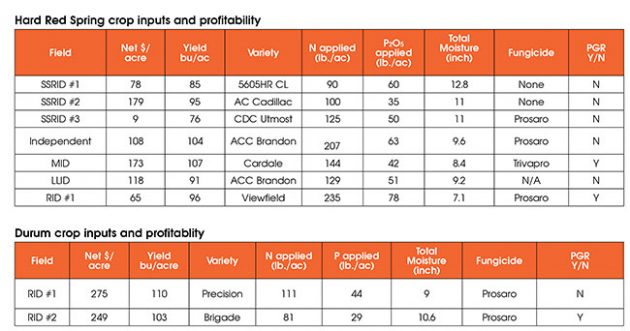

After the 2018 harvest, 10 participants provided agronomic practices and yields for spring wheat and durum wheat crops. 2018 proved to be an exceptional year for growing irrigated wheat in Saskatchewan. Spring wheat yields from the participants ranged from 72 to 107 bushels per acre (bu/ac), averaging 91 bu/acre from the eight growers located in the Lake Diefenbaker Development Area. Two grew durum in the Riverhurst Irrigation District with yields of 103 and 110 bu/ac.

“These yields are impressive and suggest yield targets of 90 to 100 bushels per acre for hard red spring wheat and 100 to 110 bushels per acre for durum are well within reach for irrigation farmers,” Peru says.

Many factors are responsible for the high yields that were seen in 2018, including the dry hot weather, which helped to keep disease pressures down.

Deliver the groceries

A wide range of production practices were reported in the survey, yet yields were consistently high for most of the farmers. Seeding dates ranged from May 3 to May 29 and did not impact yield. However, Peru cautions that based on studies at ICDC, an seeding date of May 20 or earlier has been found to provide the highest yields.

Seeding rates were generally in the 120 lb./ac range, with one field at 90 lb. Stand counts ranged from 12 to 28 plants per square foot (124 to 284 plants per square metre) based on random field sampling, and had little effect on yield. Seed treatment packages were found to be important for disease control.

Fertility packages targeted the high yields achieved in this survey. To grow a 90 bu/ac wheat crop, 135 lb./ac of nitrogen (N) and 51 lb./ac of P2O5 is required. In the survey, N applications for hard wheat ranged from a low of 90 lb. N/ac to a high of 235 lb. N/ac. The most profitable were generally found in the 100 to 144 lb. N/ac range. Phosphorus (P) rates were generally higher than recommended ranging from a low of 35 lb. P2O5 per acre to a high of 78 lb./ac.

Source: Peru and Kruger. 2018.

“They were definitely putting on the groceries,” Peru says.

Only seven out of 10 of the responders applied a fungicide for Fusarium head blight (FHB) disease control and, in the low disease pressure year of 2018, those that didn’t got away with it. However, Peru recommends a fungicide application should always be budgeted for on hard wheat and especially durum under irrigated conditions.

Research conducted by Randy Kutcher with the Crop Development Centre at the University of Saskatchewan from 2016 through 2018 in Saskatoon, Outlook, Scott and Indian Head showed the value of FHB control in durum wheat. Under the conditions of study, fungicide applied to durum wheat under high FHB severity conditions was most effective to reduce Fusarium Damaged Kernels (FDK) and deoxynivalenol (DON) between the BBCH61 to 69 (early to late anthesis) stages.

In Kutcher’s research, under low to moderate FHB severity, fungicide was of benefit; however, the window of application appeared to be smaller at BBCH 61 to 65 (early anthesis to 50 per cent anthesis). There was no reduction in DON content from the application of fungicide late in crop development at BBCH 73 (soft dough).

The optimal timing of application in the research was the same for both seeding rates of 40 seeds/ft² (400 seeds/m²) and 7.5 seeds/ft² (75 seeds/m²). The high seeding rate increased yield, but there was no interaction with fungicide application timing.

In Peru’s survey, four fields had a plant growth regulator (PGR) applied and three sites left check strips. Even though the fields produced large yields, there was no advantage to applying a PGR where check strips were left. Peru says there were apparent height differences between the treated and untreated portions of the field, although lodging was not an issue so yield losses did not occur.

“I have seen some really good results with a PGR under very good growing conditions and with varieties that are more susceptible to lodging,” Peru says.

The net return estimates done for the survey found that the cost of production for irrigated hard red wheat ranged from $462/ac to $594/ac, with net returns from $9 to $179 per acre. For durum, the cost of production was $490/ac and $468/ac, and net returns were $249 and $275 per acre. While those returns aren’t as high as dry beans or potatoes, the survey shows that, with good management practices, wheat can be a profitable rotational crop.

“I wouldn’t want to paint a bad picture for wheat. Growers are finding ways to make it more profitable by upping inputs like fertilizer and applying fungicides and PGRs,” Peru says.