Features

Herbicides

Seed & Chemical

History of herbicide resistance

Green foxtail was the first confirmed herbicide-resistant weed on the Prairies, found in 1988. Photo courtesy of Canola Council of Canada.

"This problem will strike everybody in one way or another sooner or later, and it is developing faster than people are responding to it.” That’s how Ian Morrison, who was then a plant scientist at the University of Manitoba, described herbicide resistance in a 1993 Top Crop Manager article by Rosalie I. Tennison.

At the time, Morrison’s research on herbicide resistance was triggered by the discovery of trifluralin-resistant green foxtail, the first confirmed case of herbicide resistance on the Prairies, found in 1988 in Manitoba.

“Dr. Morrison’s research team was very careful to make sure the research was done correctly and the results were valid because they knew there would be scepticism, especially among the industry players, which there was,” Hugh Beckie, who started at the University of Manitoba in 1988, says. Beckie has been focusing on herbicide resistance ever since, in his role as research scientist specializing in herbicide-resistant plants, with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatoon, Sask.

“At the time, a lot of the [herbicide] industry people had no knowledge of or experience with herbicide resistance, so they were sceptical that we would actually have herbicide resistance in Western Canada, even though Eastern Canada had been dealing with triazine resistance for many years. So there was push-back from industry [in Western Canada].”

Herbicide resistance was also a new issue for Prairie crop growers, as Australian weed scientist Ian Heap found. After completing his PhD on the first weed found to have multiple resistance (resistance to more than one herbicide mode of action, or herbicide group) in Australia and worldwide, Heap came to Manitoba in 1990 to work with Morrison for several years.

“I travelled around and tried to find out what problems farmers were having with resistant weeds. Wild oat was the biggest problem at the time – and it still is for many farmers in Western Canada,” Heap says. “All I did was look around from the road to see which fields had a lot of wild oats. Then I asked the farmer, ‘Why is your field full of wild oats?’ They’d say, ‘I don’t know. I’ve been spraying the same herbicide for years and it’s worked in the past, but in the last few years it hasn’t worked very well.’

“So, for the vast majority of farmers, resistance wasn’t even on their radar. Once they knew the cause of the problem, they were able to switch to a different herbicide mode of action and get some control.”

By 1993, Heap had found resistant wild oat, green foxtail and wild mustard, and multiple-resistant green foxtail in Manitoba.

Heap is founder and director of the Internet-based International Survey of Herbicide-Resistant Weeds (weedscience.org), which now involves weed scientists in over 80 countries.

Evolution of the issue

As Morrison predicted over 20 years ago, herbicide resistance has continued to grow. Every year, in Canada and around the world, there are more and more resistant weed species on more and more acres.

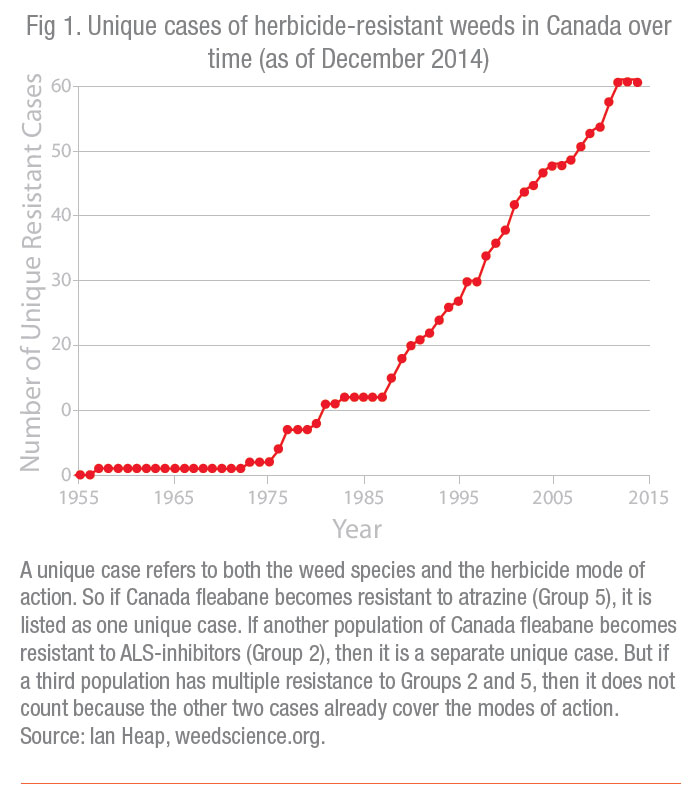

The first Canadian case listed in the International Survey is 2,4-D-resistant wild carrot, found in Ontario in 1957. Then, in the mid-1970s, the number of cases in Eastern Canada started to climb with the discovery of atrazine-resistant weeds (see Fig 1).

|

“Prior to 1970, people weren’t thinking about resistance. But in 1970, in Washington State, a researcher found a weed called common groundsel with resistance to simazine, which is a triazine like atrazine,” Heap explains. “That paper was quite an eye-opener in that farmers were applying a lot of atrazine in corn. So people started to search for resistance, thinking that maybe some of [the] weed problems in corn were because of resistance.” As a result, many cases of atrazine-resistant weeds in corn were found in the 1970s in the United States, Canada and Europe.

“Then, in the 1980s, farmers started to use other herbicide modes of action to control the triazine-resistant weeds, such as ALS-inhibitors [Group 2] and ACC-inhibitors [Group 1]. So the weeds evolved resistance to those next herbicide modes of action, and so on,” Heap says.

These days, the big concerns are glyphosate-resistant weeds and multiple-resistant weeds. And of course, some glyphosate-resistant weeds have multiple resistance such as kochia in Western Canada, and common ragweed, giant ragweed, Canada fleabane and, most recently, tall waterhemp in Eastern Canada.

Another concern is that no major new herbicide modes of action have been introduced in Western Canada in the last 25 years, and it’s hard to say when the next new one will be available. “Companies find it very difficult to register new herbicide products, and they are not searching for new herbicide modes of action as much as they used to,” Heap notes. “So for the moment, we’re pretty much left with the herbicides that we have.”

But it’s not all bad news. Important advances have occurred in several areas.

“We’ve made huge strides in the last 20 years in understanding and knowledge of herbicide resistance, and also in recommendations for best management practices to slow resistance,” Beckie says. For instance, research resulted in the recommendation to rotate herbicide groups, and then the recommendation to also use herbicide mixtures or sequences as an even more effective way to delay resistance.

More recently, researchers have been gaining important information on enhanced metabolism, a resistance mechanism in which the weed breaks down a herbicide so fast that the herbicide doesn’t reach its target site in the weed. Beckie says, “Finding widespread metabolic resistance, especially in grass weeds, not only in Western Canada but worldwide, was a milestone in terms of [the need to figure out] how to deal with weeds that are able to break down herbicides across herbicide groups. That’s where using herbicide group rotation or mixtures tends to fall apart. With the increase in metabolic resistance that we’re seeing, that is certainly a challenge with no easy solution.”

Today, crop growers are much more knowledgeable about herbicide resistance than they were 25 years ago. Beckie says, “Most growers now are fully aware of the issue and the best management practices. But on the other hand, they have restrictions in terms of their herbicide program, cropping system, etcetera, so they are trying to deal with resistance as best they can.” As well, herbicide companies are taking action, by setting up websites with resistance information, and by offering products with more than one mode of action.

What’s ahead?

In terms of how the herbicide resistance issue might evolve over the coming decades, Heap says, “One way companies are getting around the problem of resistance is to make crops resistant to a wider variety of herbicides, so even if you don’t have a new herbicide, you can use it in a new way.” So in the short-term, he expects more herbicide-tolerant crops, including ones with stacked herbicide tolerance.

He adds, “In the long-term, hopefully we can do a lot more with non-chemical weed control. I also think the companies will eventually bring some new herbicide modes of action to market. But it’s very expensive for them, and the regulations – environmental regulations, toxicology regulations – are always tightening.”

Beckie says, “I think it is inevitable that herbicides will not be playing the dominant role that they’ve had in the last 50 years. Growers will be forced to adopt a more integrated approach to weed management [including practices such as higher seeding rates, more diverse crop rotations and weed seed management at harvest]."

June 26, 2015 By Carolyn King